Formula E, an all-electric racing competition, is pioneering technology that could find its way into vehicles at a charging station near you.

On 6 December, 20 cars will race around the São Paulo Street Circuit in Brazil.

Stretching over 2.93km (1.8 miles), the course is dominated by long straights along which the cars can scream at full speed.

There are just 11 corners.

The cars will reach top speeds of 200mph (322km/h), and accelerate from 0 to 60mph (96km/h) in just 1.82 seconds.

This isn't quite as fast as a Formula One car, which can top out at 233 mph (375km/h).

But then, these cars are electric.

The São Paulo ePrix will be the first race of the 12th season of Formula E: the world's fastest racing contest for electric vehicles.

Launched in 2014, Formula E has rapidly progressed, adding additional teams and races, and building ever-faster cars.

The current cars are almost as fast as Formula One cars, which are the fastest racing cars in the world – and the next generation, announced in November, is set to be faster still.

To enable Formula E cars to reach these speeds, their designers have come up with an arsenal of tricks to squeeze every last volt out of their batteries.

The ingenuity starts with the batteries themselves, and extends to every other aspect of the cars.

What's more, many of the lessons learned in Formula E are being applied to more conventional electric vehicles – helping to drive the electric vehicle revolution and cut global greenhouse gas emissions.

Vroom-vroom

At their absolute core, the batteries in Formula E cars are utterly typical.

"The battery in your TV remote has the same fundamental chemical reaction as the battery cells that are used in all road vehicles and motorsport batteries," says Douglas Campling, general manager of motorsport at Fortescue Zero in Kidlington, UK.

All batteries have two main components: the cathode and the anode.

When the battery is being stored, the two are separated by internal barriers.

But when the battery is in use, the two are connected in a circuit, and electrons flow from the anode to the cathode.

This flow of electrons is what powers an application – whether it's a smartphone or a race car.

However, designing a battery that stores enough energy to power a race car at top speed, and to keep it going for the entire race, is a big challenge.

In the early days of Formula E, it had not been achieved.

"If you look at those first few seasons, because the battery range wasn't where it is today, our drivers, very memorably, had to switch cars in the middle of the race," says Beth Paretta, vice president of sporting at Formula E.

Eleven years on, the drivers can now finish a race in the same car they started.

Partly, this is because the newer batteries can store much more electrical energy than the older ones.

Today, Formula E drivers start a race with about 52 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity in the battery, enough to power a fridge-freezer for almost two months.

However, simply packing in a lot of energy isn't enough: the battery must also be able to release that energy quickly and flexibly.

"The Formula E pack can deliver and receive any energy at a power of 600 kilowatts," says Campling.

That's a little over 800 horsepower.

"Whereas the battery in your Toyota Prius will do less than half of that."

There is also a third metric, called the C-rate.

This is similar to the power, in that it measures how quickly the battery can discharge, but it is calculated relative to the battery's capacity: in other words, it tells you how quickly the entire battery can be discharged.

"The C-rate of the cells that we use in the Formula E battery today is extremely high," says Campling, allowing them to be charged and discharged rapidly.

Achieving all this requires stacking a great many battery "cells" into a single package.

Each cell is about the size of an A5 notebook, and they are stacked into modules of a few hundred each.

Between each pair of cells is a cooling plate.

There are also structural members that give the battery assembly some strength – and, crucially, provide some rigidity for the entire chassis of the car.

"The chassis itself wouldn't pass the squeeze test and the torsional stiffness test that it needs for its own performance," says Campling.

Using the battery to provide strength saves on weight.

The batteries use lithium-ion chemistry, which is common in electric vehicles.

However, they use a variant that includes the metals nickel, manganese and cobalt, known as NMC.

"It allows for the higher-power applications," says Campling.

All this means that the batteries are optimised for high-speed racing.

But there's still, on the face of it, an energy shortage.

While a Formula E car starts with at most 52kWh, "the race itself can consume up to something like 90kWh", says Campling.

"When they start the race, they only have 65% of the power to finish the race," says Paretta.

"If they just put their foot to the floor, they wouldn't finish the race."

Charging

The designers solved this using two tricks.

The first is to generate energy from braking.

"The motor on the front axle and the motor on the rear axle go into generator mode," says Campling, which means the wheels are turning the motor, rather than the other way around, allowing the motor to recharge.

This means the rear axle doesn't have standard friction brakes at all.

Such brakes are a source of particulate pollution, so deleting them removes a source of air pollution, as well as generating electricity to power the car.

To accommodate regenerative braking, Formula E often adds corners or even chicanes to existing tracks.

"We have to make sure that there's enough of those braking zones, because we want them to regenerate that energy," says Paretta.

The second trick, introduced in the most recent season, is to recharge the cars mid-race.

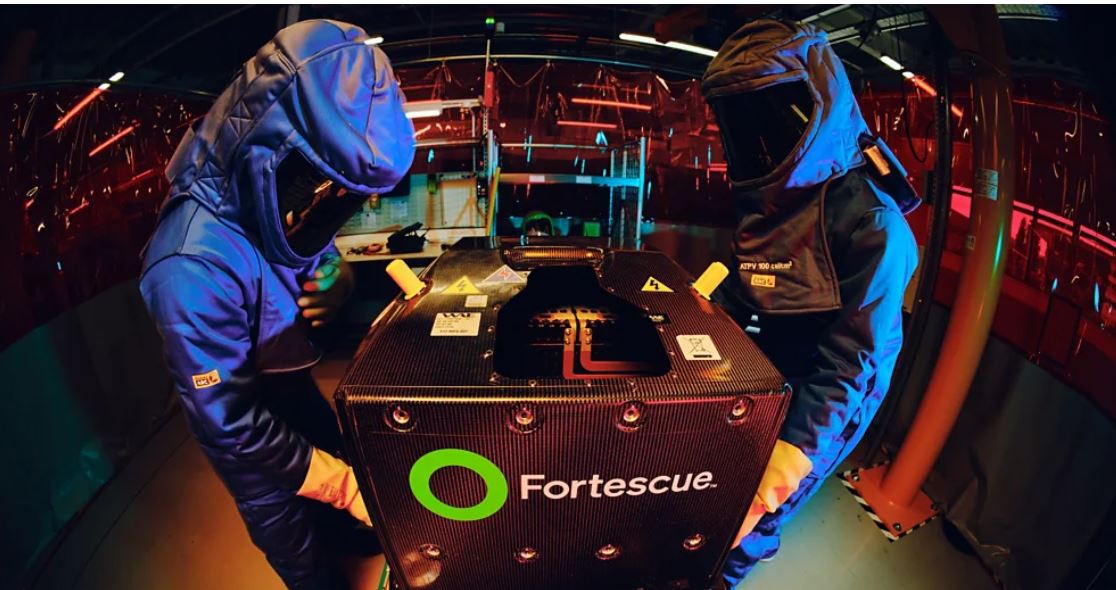

A technology called Pit Boost, developed by Fortescue Zero, allows very fast charging.

Cars enter the pit lane, like in a Formula One race, and come to a stop.

They are then plugged in and receive 3.85kWh in 30 seconds.

The electricity is delivered at 600kW, about four times what the fastest commercially available chargers can manage.

For the sport, the idea is to add a layer of strategic complexity: when should the drivers come in for a charge?

In the final laps of a race, TV broadcasts show how much energy the cars have left, creating suspense over whether drivers will run out before the end.

But this fast-charging technology could also be applied to normal electric vehicles.

As the range of electric vehicles has improved, "range anxiety has kind of gone away", says Campling.

In its place has come charge anxiety.

"Can you actually get onto a charger when you want one, and where you want one, and how long are you going to be stuck there for?"

Part of the solution is of course more chargers, but for car manufacturers, faster charging will also help.

"What they can do is say, 'Our cars will charge faster than our competitors'."

In fact, many of the approaches developed for Formula E could ultimately be transferred to normal electric vehicles and hybrids.

For instance, Fortescue Zero developed a battery management system called Elysia which uses sensors and automated software to detect faults and improve performance.

It is being added to all Jaguar Land Rover vehicles, enabling improvements like faster charging.

Existing motoring technologies like rear-view mirrors and anti-lock brakes were developed for racing, and the same will be true for future vehicles.

"The racetrack is a laboratory, and always has been," says Paretta.

When those race cars launch from the starting line in São Paulo, they will be carrying technology that will be in your car in a few years' time.