Declining Nile perch and tilapia stocks, fish diseases, uncontrolled proliferation of fish farms and rising water levels are some of the challenges faced by Lake Victoria fishing industry.

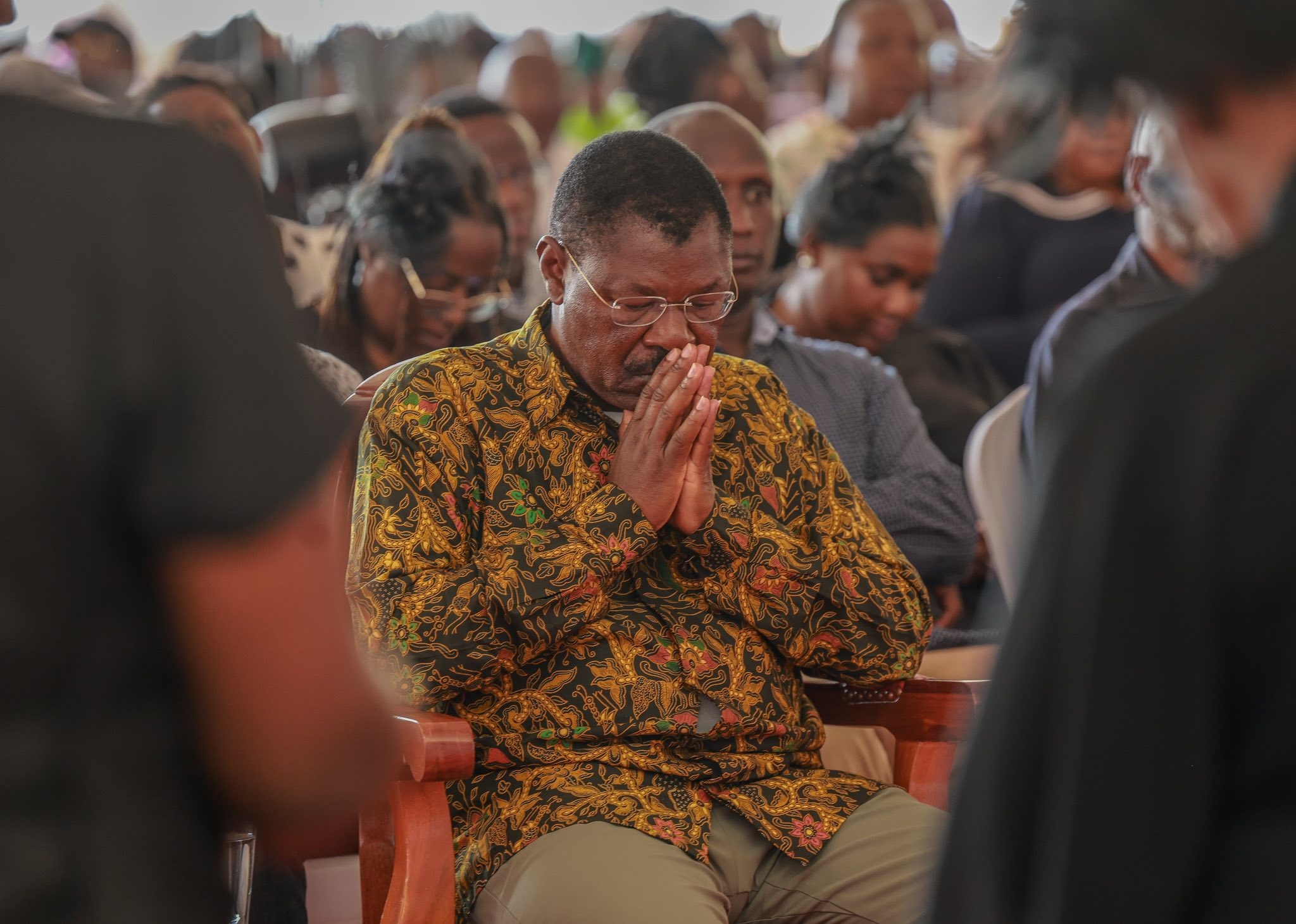

East African Community secretary-general Peter Mathuki, citing the problems, said a remedial project was launched by the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation, a specialised institution of the EAC based in Jinja, Uganda.

Mathuki said the True Fish project was designed to address impediments to growth in aquaculture faced by investors; for instance, lack of technically skilled operators, lack of investment finance and business planning and incomplete networks.

“The second objective of the project is to address identified threats, which could undermine the sustainability of aquaculture development, impact the environment negatively, food security or livelihoods, especially biosecurity risks such as fish diseases and introduction of non-native species that has led to the loss of biodiversity,” Mathuki said in a speech read by EAC Customs and Trade director-general Kenneth Bagamuhunda.

Bagamuhunda attended the launch of the project in Arusha. It will cost about Sh1.3 billion.

LVFO executive secretary Shigalla Mahongo said the European Union Commission is financing the project under the 11th European Development Fund Regional Indicative Programme.

“The EDF contribution is 10 million Euros, while 150,000 Euros is co-financed by potential grant beneficiaries,” Mahongo said.

He said despite efforts of the countries around Lake Victoria to ensure the sustainability of the traditional fishing methods, demand for fish had increased because of increased population, incomes and urbanisation.

“The capture fisheries of Nile perch and tilapia are no longer able to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for fish in the region.”

He said despite global aquaculture production surpassing harvests from capture fisheries for the first time in 2014, fish farming in the EAC region is still at its infant stage, accounting for only seven to eight per cent of fish consumption.

“The overall demand for fish in the region will continue increasing, thus developing aquaculture to meet the ever-increasing demand for fish is inevitable,” Muhongo said.

Jose Parajua, a fisheries technical adviser at the Food and Agriculture Organisation, described the negative impact of the introduction of the Nile perch species on Lake Victoria almost six decades ago.

“The entire food web in the lake underwent all kinds of changes due to the voracious Nile perch. Many small and colourful fish species disappeared from the lake forever. The Nile tilapia that was also introduced a few decades earlier wiped out some original other tilapia species,” Parajua said.

“In that dynamic interaction between nature and fisheries, LVFO had to make decisions on how to assure food security for the riparian populations while looking after the economic interests of the neighbouring countries through the continuous export of the largest money-maker, the earlier-mentioned Nile perch.”

He said LVFO could not stop the influx of numerous additional fishers and fishmongers, among others involved in the value chain, and the overexploitation of the perch became a fact.

“The Nile tilapia was hit hard by the fishing intensity, but nature came up with a solution as there was suddenly much space for a small fish species, also known as dagaa in Tanzania, mukène in Uganda and omèna in Kenya,” he said.

Parajua said Nile perch is very important for the food and nutrition security of the people residing around and far from the lake.

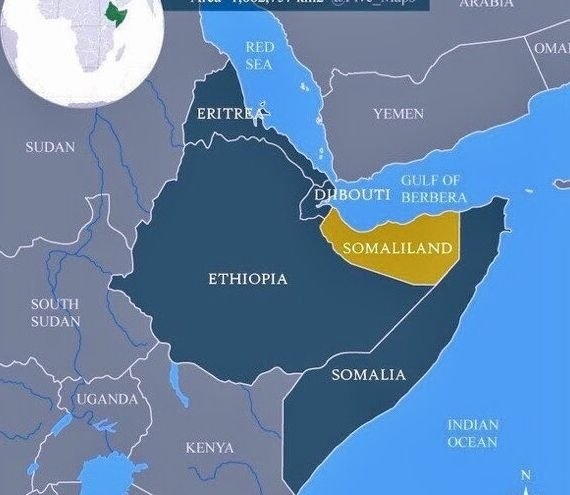

“The dried form of this fish found its way to Burundi, DR Congo, South Sudan and beyond. As the quantities fished were enormous, this species found its way into poultry feed producers and eventually also into fish feed,” he said.

“There was the continuous demand for fish from the lake. If the fisheries could not supply the fish then fish had to be reared outside the lake. Many entrepreneurs started fish farms for Nile tilapia and the African catfish.”

Parajua said the climatic conditions in the region are very conducive for fish culture in fishponds, but the region needed more fish and that was the genesis of cage farming on the lake.

“Why not grow the fish inside the lake, in floating cages? Once this idea was born and the results appeared encouraging, the numbers of cages started mushrooming,” the FAO expert said.

“Small square cages initially with volumes of a few cubic metres, followed by larger circular ones, which could contain tens of thousands of fish each.”

Parajua said the development of cage farming could easily have gone out of hand, hence it became imperative for LVFO to prepare guidelines for cage culture development and management.

“However, the concerns were too many. Questions were raised about the possible pollution of the lake if leftover fish feed entered the lake,” he said.

“What about fish excrements? Where should the farms be located so that conflicts with capture fisheries could be avoided, particularly in the light of spawning and nursery grounds of other fish species?”

Edited by Kiilu Damaris