In October last year, World Wildlife

Fund planet report 2024, painted a

grim picture of a shocking decline

of iconic species.

The report showed there has been a catastrophic 73 per cent decline in the average size of monitored wildlife populations in just 50 years ( 1970- 2020 ).

The report warned that parts of the planet was approaching dangerous tipping points driven by the combination of nature loss and climate change which pose grave threats to humanity.

The Living Planet Index, provided by the Zoological Society of London, tracks almost 35,000 vertebrate populations of 5,495 species.

The steepest decline is in freshwater populations ( 85 per cent), followed by terrestrial ( 69 per cent) and then marine ( 56 per cent).

Habitat loss and degradation and over-harvesting, driven primarily by global food system, are the dominant threats to wildlife populations around the world, followed by invasive species, disease and climate change.

A significant decline in wildlife populations negatively impact the health and resilience of the environment and push nature closer to disastrous tipping points– critical thresholds resulting in substantial and potentially irreversible change.

There is need to put in place strategies to reverse this worrying tends. It is for this reason that a community on the outskirts of the Amboseli ecosystem have started devising ways to create more room for elephants to roam.

The 28,784-acre Illaingarunyoni Conservancy, northwest of Amboseli National Park, is a critical wildlife dispersal area and habitat for unique species not regularly seen in other parts of Amboseli.

These include bat-eared fox, lesser kudu, the African wild dog, pangolin and aardvark. The area is also a natural gateway for 2,200 endangered African savannah elephants to move between Amboseli and the Loita–Maasai Mara ecosystem.

The Amboseli National Park is a remnant of the 27,700km2 Southern Game Reserve established in 1906.

This reserve, according to Kenya Wildlife Service, was reduced to 3,260km2 in 1948 and was named Amboseli National Reserve and placed under the administration of the National Park Trustees.

In 1961, the same area became a County Council Game Reserve administered by the defunct Kajiado county council.

In 1971, due to the realisation of Amboseli’s unique values and the need for more intensive management, a presidential decree was issued declaring that an area of 390Km2 be set aside exclusively for wildlife and tourism.

In 1972, the new wildlife sanctuary boundaries were demarcated, and the area was gazetted as government land.

In October 1973, the Amboseli National Park was finally established and again was under the control of the National Parks Trustees.

Most wildlife in the park spend their time outside the protected area, making community-owned lands surrounding it a vital lifeline to both the Maasai and wildlife.

The area within Illaingarunyoni Conservancy is rich in fodder and previously provided dry grazing reserve for livestock.

The International Fund for Animal Welfare through its flagship project—Room to Roam—is helping the conservancy enhance connectivity so animals and people can thrive.

FAW is a global non-profit helping animals and people thrive together. It has secured the Illaingarunyoni Conservancy through a formal agreement with the Olgulului-Ololorashi Group Ranch landowners.

The deal improves landscape connectivity by securing additional wildlife areas and room for elephants to roam.

It covers vast areas from the Kilimanjaro ecosystem in Tanzania to Kitenden Conservancy, through Amboseli National Park and further to lush grazing grounds in Moshi and Mount Meru in northern Tanzania through the Kajiado-Magadi-Loita elephant migration corridor.

The new conservancy also provides opportunities for local communities to benefit through wildlife-based economies in line with IFAW’s mission of ‘animals and people thriving together’.

Examples include conservation easements, ecotourism and other forms of payment for ecosystem services and essential revenue streams for disadvantaged communities.

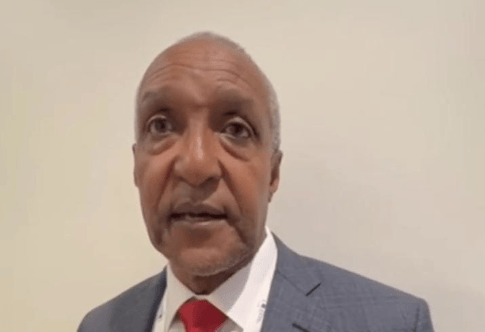

Illaingarunyoni Conservancy secretary George Lupembe said they are looking for an investor to put money in the conservancy.

“We already have a one ranger’s post with 10 ranger’s posts and IFAW support with the mobility and food and even uniform to carry day-today activities of the conservancy,” Lupembe said.

The rangeland has minimum rains with short rains coming November and December. He said grazing committees ensure the available grass is utilised well through zoning.

The land is also shared with wildlife as it has no fences. Lupembe who is also the Loolaki chief, said IFAW also supports them pay land rates which is yet to be paid to land owners.

He said they are in the process of preparing the register so that every member will be given Sh15,000.

“We have done a biodiversity survey and we are planning to have a management plan for the conservancy. We have also trained the committee on governance.”

Lupembe said the land has 3,598 members with each member donating eight acres. Since the conservancy is huge, there is a need for more ranger’s posts.

The move, Lupembe said, will help take care of the landscape, provide jobs to the community and ensure wildlife thrives.

As part of the project, several initiatives such as bee keeping and growing of grass have also been initiated for the community to reap benefits.

IFAW President and CEO Azzedine

Downes said as pastoralists, Maasai

people have coexisted with wildlife

for years, so they hold values that are

already in line with how IFAW works

to develop peaceful coexistence between humans and wildlife.