At 7:30 am on Wednesday, a Kenya Wildlife Service helicopter roared into the open skies of the Nakuru National Park.

On board were four census officials on a mission to count the country's iconic species at the park.

The data crew included a pilot, a front seat observer and two rear seat observers on the left and on the right side.

During the census, experts exuded confidence that the exercise would generate crucial data to aid decision-making.

The crew was keen to determine the number and distribution of large mammals.

The methods used for the census include aerial counts, ground counts, and spatially explicit capture-recapture for carnivores.

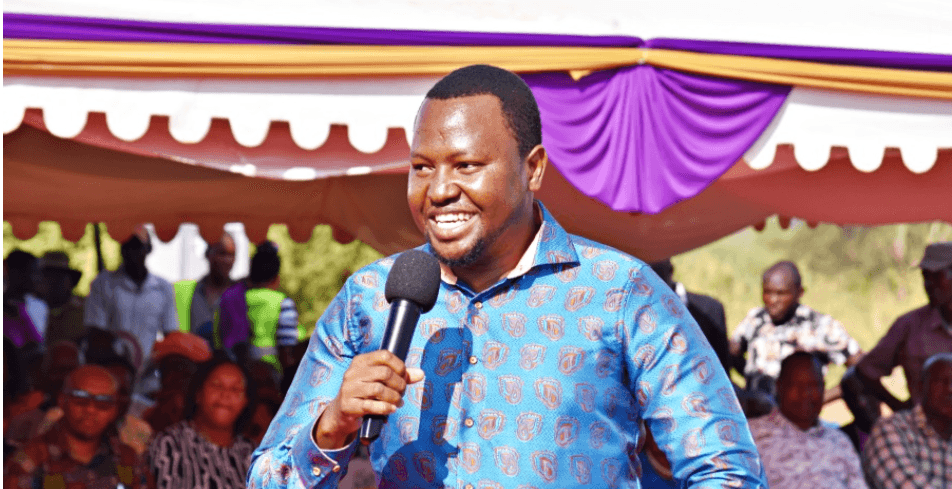

Wildlife Research and Training Institute head of research Dr David Ndeereh said the enumeration is part of Phase One of the national exercise launched on June 19.

“We have been able to cover several landscapes, such as the greater Maasai Mara ecosystem, the Amboseli-Magadi ecosystem, Athi Kapiti, and Naivasha Nakuru ranches,” he said.

Any animal bigger than Thomson gazelles was counted.

Ndeereh said fixed-wing aircraft, which are heavier, were used in other areas, but a helicopter was ideal for the park, which has a high density of wildlife.

The census covers the greater Masai Mara ecosystem, Amboseli/Magadi, Nairobi Athi-Kapiti landscape and all the closed sanctuaries, including Solio, Mwea, Lake Nakuru and Ruma national parks.

Within phase two, there are enclosed ecosystems - those that are fenced - and helicopters are used in such closed areas.

“So far, we have been able to do Mwea National Reserve, Solio and Ruma National Park, and today (Wednesday), we are here at Lake Nakuru National Park,” Ndeereh said.

The data being collected will inform management decisions as well as policy formulation, which are needed as the country pursues efforts to enhance conservation and management of wildlife.

“It will also assist us in accessing the land use changes because the country is undergoing a lot of changes in terms of land uses. There is a lot of demarcation of lands and conversion of the same lands for different uses.”

Census officials will thereafter move to the marine ecosystem along the Kenyan coast, which will mark the end of the first phase.

The wildlife sector has embraced new and emerging technologies, he added.

“Currently, we are using the remote sensing technology that will assist us in accessing the habitat changes over time since we did the first census in 2021,” the conservationist explained.

On landing, data captured in a dictaphone - a device used to record sound or speech - is downloaded and transcribed into a database.

GPS data, consisting of tracks and waypoints (coordinates to identify a location) are downloaded and merged with the transcribed voice data.

Data is then cleaned in order to identify and eliminate any possible double counts.

Images are also taken using cameras.

He added that Earth Ranger, which is also an integrated technology, has been adopted and is being used in mapping and observing movements of various wildlife species, especially those animals that have been fitted with monitoring devices.

“We have animals, including elephants, giraffes, and lions, that we have fitted devices to assist in monitoring them in real-time.”

Ndeereh said a lot of data have so far been collected that will take time to analyse.

There is a need to connect all the dots before any conclusion is made, he said, adding that data has to be verified.

“The technical team will retreat to do further analysis on the data collected so far so that we can be able to tell the country the changes in wildlife numbers and distribution. It is still very early to mention numbers,” Ndeereh said,

After all the data is analysed, a report is done.

A wildlife census should be undertaken every three years in line with ecological cycles of fertility and mortality.

Kenya is seeking to increase wildlife conservation areas in accordance with the global biodiversity framework that recommends that each country have at least 30 per cent of landmass under conservation.

The conservationist underscored the importance of the census.

“We want to update our wildlife numbers in space and time. Since we conducted the first comprehensive wildlife census in 2021. The country experienced severe drought in 2022 and then flooding in early 2023. Those two events had impact on wildlife,” Ndeereh said.

Wildlife are tourist products, he explained, saying it was therefore important for the country to know what species it has, in order to inform the management of the resource.

The census follows one conducted from May to August 2021, that generated baseline numbers of wildlife.

The results have been used to review the National Wildlife Strategy 2030 and the current review of the Wildlife Act.

The current count is being carried out at a cost of Sh302 million, with the Tourism Promotion Fund, which provided Sh60 million, supporting the first phase.

The 2021 census covered 343,380km square of Kenya’s land mass at a cost of Sh250 million.

The census showed 36,280 elephants, 897 black rhinos, 842 white rhinos, two northern rhinos, 2,589 lions, 5,189 hyenas, 1,160 cheetahs, 865 wild dogs, and 41,659 buffalos.

The second phase will commence in November.

“Phase two will involve all the other areas where wildlife exists in Kenya,” Ndeereh said.