In the winding alleys of Mathare, one of Nairobi’s oldest and most densely populated informal settlements, creativity thrives in the unlikeliest corners.

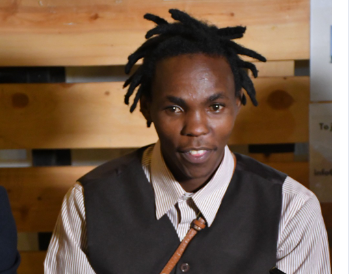

Amidst the daily challenges of survival, injustice and economic hardship, Samuel Waweru, better as Anthem Republiq (Republic Anthem), is using poetry, performance and community organising to transform community pain into purpose.

A poet, actor and creative consultant, Anthem is also the founder of Starifik — a co-working and learning space empowering Mathare’s youth through art, innovation, and technology. But it’s just not about creative expression. It’s also about survival, resilience, identity, dreams and social harmony.

“Art is how I make sense of this beautiful and complicated world. It is how I connect with myself and people,” Anthem says.

“It’s how I go places, it’s the way I get what is mine. It’s my way of life and it is who I am.”

Mathare is a collection of slums in Nairobi, covering about 3.5 square miles and populated by more than 700,000 residents. It’s the second-largest informal settlement in the capital, after Kibera.

Growing up in Mathare, and surviving there, is not for the faint-hearted. From an early age, Anthem was exposed to both the best and the worst of life there, including diversity, friendship, smiles, poverty, police violence, crime, drugs and discrimination.

And there were and are monetary, alcoholic and other lures thrown to the youth by power-seeking individuals, who exploit young men.

The community often feels abandoned, stereotyped, and forgotten by the systems meant to serve them.

“Sometimes you feel like you’re a burden to society, like you don’t belong, like you have to beg for a dignified life,” Anthem says.

He recalls how early on, people would look at him differently just because of where he came from.

“I couldn’t even tell my girlfriend I was from Mathare,” he says.

Most people’s attitudes and actions changed immediately after they heard where he lived, including actions such as hiding their phones.

“I started saying I was from Pangani, just to avoid the stigma,” Anthem recalls.

These experiences planted the seeds of his art. What began as a hobby — writing and performing for fun — soon evolved into a powerful outlet for confronting social injustice.

It wasn’t just discrimination that haunted Anthem’s youth. It was the death toll of extrajudicial killings that loomed large in his community. Friends, schoolmates, and neighbours, many with big dreams, were cut down, often accused of petty crimes, sometimes without given a chance to speak or defend themselves.

“I’ve seen people killed for things I couldn’t believe, including accusations of theft. I knew them differently. It made me fear for my own life. I started wondering if this was the destiny for every young man in the ghetto,” Anthem says.

He briefly considered documenting the killings undercover, filming secretly to gather evidence. But fear, his own and that of his friends, made it impossible.

That’s when he turned full time to writing. His words, he realised, could become his weapons.

“I didn’t even know what social justice was at the time. I just knew that through writing, I could ask why things were the way they were.”

One of his most emotional pieces, the poem Peace, was written after the trauma of the 2007-08 post-election violence. During that period, his mother remained in Mathare with his younger sisters, while he had been sent to the village awhile back to pursue his education. It was also his mother’s way of keeping him away from the “street disease”.

Anthem was not at peace when the violence broke out and he kept making frantic calls home, calls marked by screams, gunshots and slashing pangas in the background.

“I couldn’t focus on my studies. Every call was filled with fear. Eventually, I returned to Mathare against my mother’s wishes and found homes burnt and friends gone in the aftermath of ethnic violence. That anger gave birth to Peace, my first real piece on social harmony,” Anthem says.

The poem was a plea to ethnic groups to stop fighting wars started by the enemies of social harmony. Aiming to produce a video of the poem, Anthem was introduced to Samuel Kiriro, founder of the Ghetto Foundation, and eventually, to the Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC) by Stephen Mwangi Kinuthia, also known as Militant, a community social advocate.

There, he found a community of truth-tellers who were unafraid to speak up and stand for a dignified life.

“That space allowed me to find my voice, and others like me who refused to normalise injustice,” Anthem says.

In another moving piece Tembea Ghetto, Anthem challenges the narrative that people from slums are inherently dangerous or unworthy. He performed it in different places, parking conversations about dignity and pride in one’s origins.

“I didn’t choose to be born here. God gave me this space. So, I embrace it, find joy and strive to make it better — for me and for those around me,” the poet and social harmoniser says.

Through performance and public speaking, Anthem helped people in the community begin to reclaim pride in their identity. For years, many were ashamed to say they were from Mathare.

Now, many young people are proudly asserting where they come from — and demanding a better future.

“Art gave me the right to question,” Anthem says, “and the community started listening.”

As his work gained visibility, people began to view him in a different light — artist, leader, and an ambassador for peace and mental wellness.

“Everything is political,” he observes. “Even silence is political. If you’re not contributing to the solution, you are part of the problem.”

His boldness to speak out on issues such as extrajudicial killings earned him admiration and skepticism. Some saw him as a social connector, others as a disruptor. But many are beginning to understand the necessity of his voice.

“Art is not just entertainment, but also a powerful tool for transformation,” Anthem says.

He believes Kenya is entering a turning point. Conversations are shifting, and communities are beginning to organise around real issues — policy, governance, equity, peace and social harmony.

“We are not just talking, we are doing,” Anthem says.

“People will know their contribution to society. Youth won’t be used or silenced by fear or intimidation. We’ll have sober youth ready to transform the country.”

He believes the healing of communities comes through collective work, empathy,

and the courage to ask hard questions. His mantra, “Tunahealtukiheal, Mpaka

Iwake”— “We heal as we help others heal” — sums up his journey and his dream.

“It’s not just about me anymore. It’s about all of us. The community is the solution — and the community is built by the people.”