The January forecast

The January forecast

The forecast points to reduced rainfall and higher-than-average temperatures in most parts of the country. The drier and hotter weather is likely driven by the weak La Nina that is currently developing.

“The outlook indicates that a majority of Kenya will experience drier-than-usual conditions,” said a three-month report by the IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC).

The Kenya Meteorological Department also said sunny and dry weather conditions would dominate most parts of the country between January and March. Temperatures are expected to be warmer than average across the entire country.

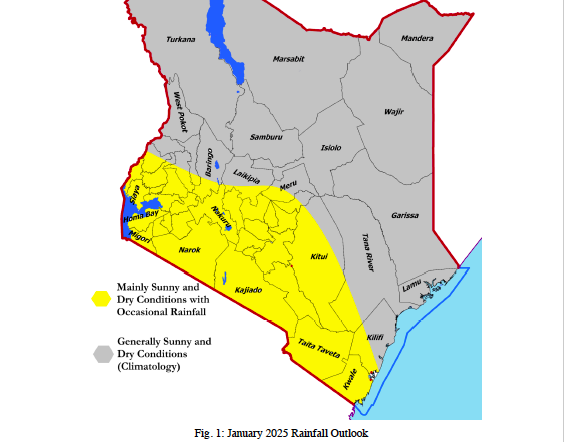

“A few areas in the Highlands West of the Rift Valley, the Lake Victoria Basin, Central and Southern Rift Valley, as well as the Highlands East of the Rift Valley, the Coastal region, and the Southeastern lowlands, may experience occasional rainy days during the forecast period,” said KMD Director Dr David Gikungu.

“This rainfall is likely to spread to several places in the Highlands West of the Rift Valley, the Lake Victoria Basin, and Central and Southern Rift Valley by March.”

Dr Gikungu said the month of January would be mainly sunny and dry across most parts of the country. He said a few areas near Lake Victoria, Rift Valley highlands and counties near Mt Kenya may experience occasional rainy days.

“This rainfall is expected to be near to below the January Long-Term Mean,” he said in a statement.

He urged farmers, pastoralists, and local planners to prepare for the potential impacts. Agriculture—a sector that contributes significantly to Kenya’s economy—could face challenges if the anticipated dryness stretches beyond the forecasted period.

“Increased temperatures and reduced precipitation may exacerbate water scarcity, putting pressure on irrigation systems and livestock,” the report warns.

Dr Gikungu said, currently, La Nina is neutral. Historically, La Niña has been associated with droughts and adverse weather conditions, which has generated concern, particularly in northern Kenya.

The last prolonged La Niña event occurred between 2020 and 2023, caused droughts and a water crisis across Kenya. Two weeks ago, forecasts from World Meteorological Organization Global Producing Centres of Long-Range Forecasts indicated a 55 per cent likelihood of a transition from the current neutral conditions (neither El Niño nor La Niña) to La Nina conditions during December 2024 to February 2025.

“The return of the ENSO-neutral conditions is then favoured during February-April 2025, with about 55 per cent chance,” WMO said in a statement.

La Niña refers to the large-scale cooling of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, coupled with changes in the tropical atmospheric circulation, such as winds, pressure and rainfall.

Generally, La Niña produces the opposite large-scale climate impacts to El Niño, especially in tropical regions.

However, naturally occurring climate events such as La Nina and El Nino events are taking place in the broader context of human-induced climate change, which is increasing global temperatures, exacerbating extreme weather and climate, and impacting seasonal rainfall and temperature patterns.

“The year 2024 started out with El Niño and is on track to be the hottest on record. Even if a La Niña event does emerge, its short-term cooling impact will be insufficient to counterbalance the warming effect of record heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere," said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

“Even in the absence of El Niño or La Niña conditions since May, we have witnessed an extraordinary series of extreme weather events, including record-breaking rainfall and flooding which have unfortunately become the new norm in our changing climate,” said Celeste Saulo.

As of the end of November 2024, oceanic and atmospheric observations continue to reflect ENSO-neutral conditions which have persisted since May. Sea surface temperatures are slightly below average over much of the central to eastern equatorial Pacific.

However, this cooling has not yet reached typical La Niña thresholds. One possible reason for this slow development is the strong westerly wind anomalies observed for much September to early November 2024, which are not conducive for La Niña development, WMO said.

The previous Update, issued in September, forecast a 60% likelihood of la Niña in December-February.

Seasonal forecasts for El Niño and La Niña and the associated impacts on the climate patterns globally are an important tool to inform early warnings and early action.