Children playing. For insurance to work, there must be enough healthy people.

Children playing. For insurance to work, there must be enough healthy people.

BY DR RICHARD AYAH

January is the month of new year resolutions, not of counting your chickens. As a group, chickens, once they hear the words “happy new year” are happy.

They begin to calm down and look forward, at least to some life. Different from human beings, who, by the middle of January, are broke and sad. Counting the days to the end of the month, the thought of chicken, is a distant memory of the Christmas period. An interesting question however is, what is it with us and chickens?

Why do we, and here, think of certain communities in particular, value eating chickens so much? The history of the chicken is a curious one. The domesticated bird that we call chicken is descended from the jungle fowl, native to India and South-East Asia. In the wild it is not a large bird. It can fly very short distances and take off almost vertically to land in trees, to escape predators. It roosts in trees, hence the name rooster.

In its native form the jungle fowl is a tropical bird found where temperatures are ten degrees and above. About 8,000 years ago, humans discovered that the jungle fowl could work as food for several reasons. First it did not fly very far, no matter what. It hung around all year, did not migrate to distant lands at certain times of the year.

Lastly, it was good to eat. So began a process of domestication and travel. Humans started breeding the jungle fowl, now called chicken, to have fat thighs and large breast muscles, which made it even harder for it to fly. Over the last 4,000 years the chicken has spread so that it is now found all over the world.

The main period for the spread of chicken in Europe was during the iron age, and much later to Africa and Americas. Scientists have studied the origins of the African chicken, and they find that as in all things African, it is complex. We still do not know for sure, when domestic chickens were first adopted by African societies and for what purposes.

There is no single event when chickens entered Africa, but rather stories of multiple historic and repeated introduction of the chicken. It seems that among the early trade routes, from China, India and Africa, chicken was one of the few animals that was voluntarily traded.

What may be of interest to readers is that Kakamega, western Kenya, is at an altitude of 1,500m and the average temperature is about 20 degrees centigrade, ideal climate for chickens to grow, but far away from the trade routes of the world.

So, what does all this history about the chicken have to do with health? Apart from the huge quantity of chicken that we grow and eat every year? One way to think about the chicken is to think about how things about the chicken has entered our everyday language.

That is homework. Another is to ponder, the decision the chicken made, 8,000 years ago, not to fly away. What made the chicken decide, as a group that life was better living close to human beings, it will get food easily, but in the process will not live very long. Was that a good decision? From an individual chicken perspective, it may not make sense, but perhaps from a community perspective it may? But does it?

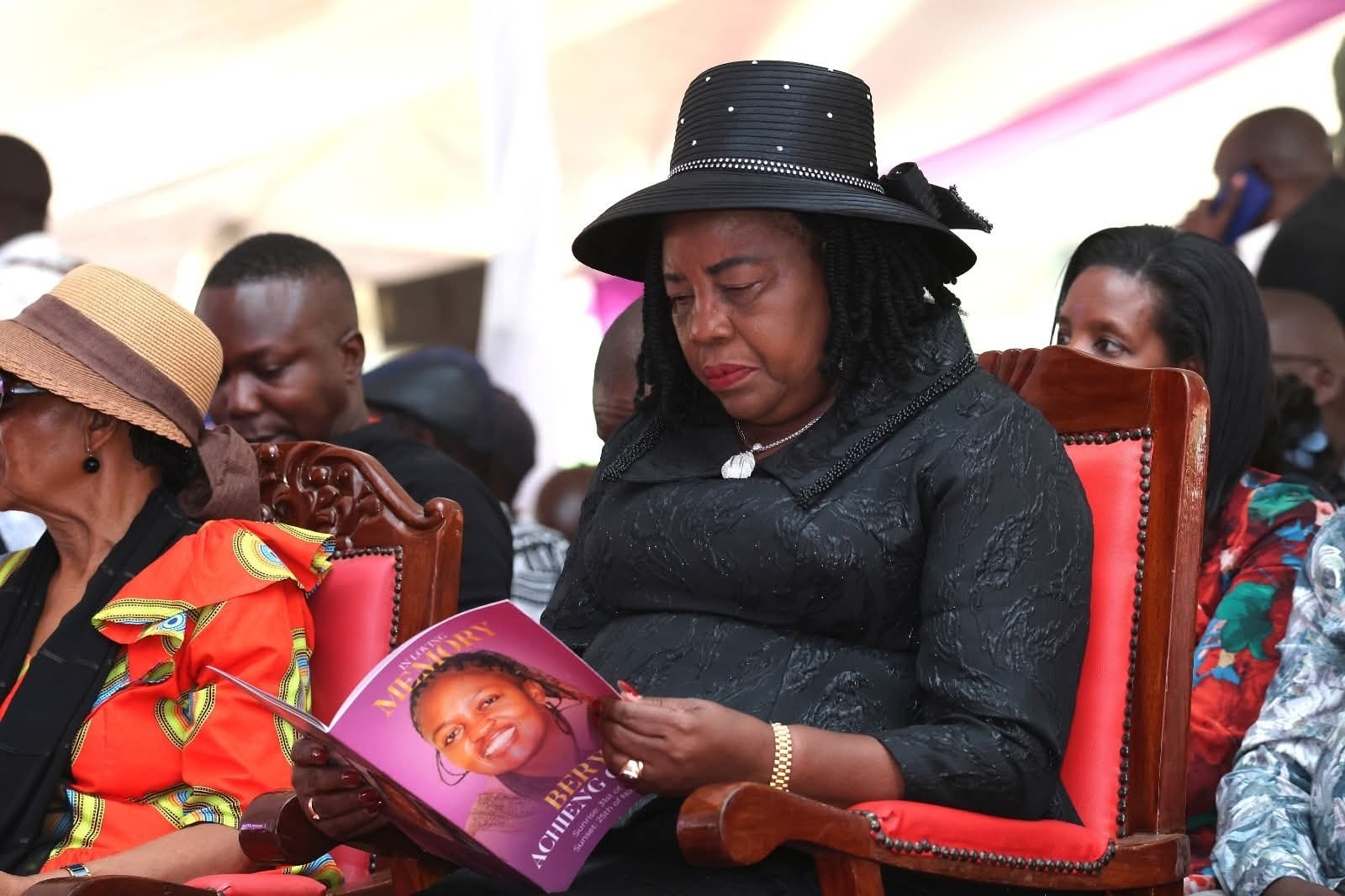

Here is one way to think about. Social health insurance is about pooling resources together to achieve health for all. The theory is that we all need healthcare at some point in life, but we do not know when.

The all part is the social, bit, the need for healthcare is when there is no health, and the insurance part is the uncertainty of when you will fall ill. For social health insurance to work, there must be enough people healthy, so that only a few people need healthcare at any one point.

Then, there needs to be enough resources, and the resources need to be in a form that can be mobilised to look after those who are ill until they recover. Kenya as a country struggle with all three requirements for social health insurance.

A significant portion of our population is sick, all the time. We have 1.5 million persons living with HIV, we have one of every four adults with a non-communicable disease like hypertension, not to mention the more than 3,000 persons killed on the roads every year. Then we have an extensive prevention program, for example about 1.5 million babies require immunization every year.

Insurance does not work for an event you know will happen. Then there is the resource requirement. Africans talk about being in a rich continent but lack the means to turn those riches into resources we can use. Kenya is no exception, we are still a lower middle income country, unable to properly mobilise resources for public use properly.

That is why we have the tag, ‘lower’ in our country description. In evolution terms, the chicken has spread all around the world. In western Kenya it is revered. Wherever you find a human being a chicken will be nearby, if not live, then as a food.

Useful for human beings. Perhaps if it had a choice to think through the theory of the deal, it might have made a different decision? What do you think?

Dr Richard Ayah is public health practitioner in Nairobi.