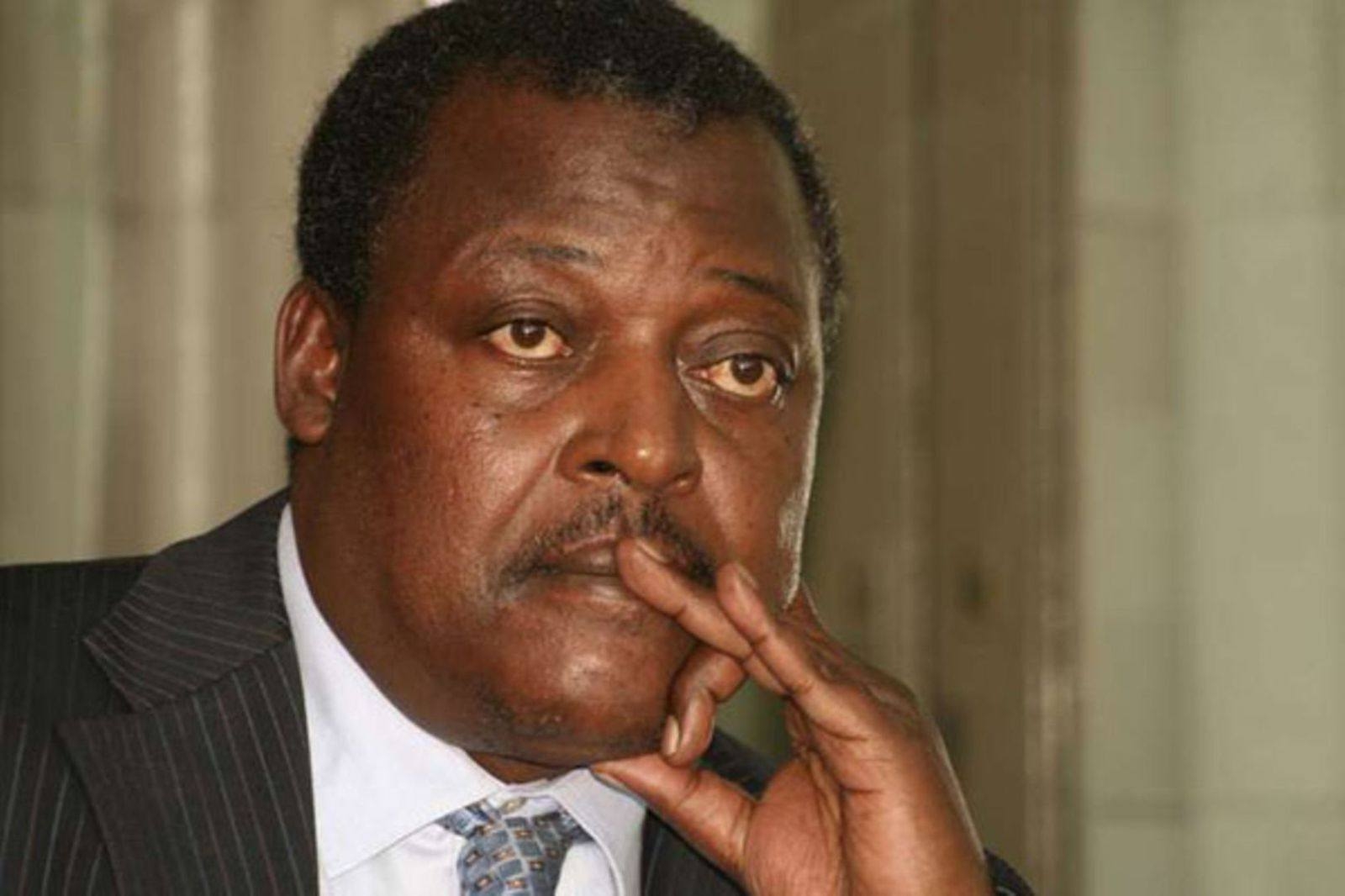

Lately, Dr Mukhisa Kituyi’s favourite phrase is ‘Enterprise Kenya’. That’s a country not merely surviving but prospering and fulfilling its obligations to its people.

But don’t get it wrong. The man who can readily talk shop and jargon has his roots in the deepest struggle for Kenya’s Second Liberation. He may not show it but he is alive to his painful peasantry background.

Journalist Isaac Otidi Amuke replays his two-hour conversation with Kituyi, as the former Unctad secretary general shares his trials, tribulations, triumphs and ideas on Enterprise Kenya.

This is the second of three parts.

After Mukhisa Kituyi was done with Makerere University in February 1982, bringing back a BA in Political Science and International Relations, Dr. Apollo Njonjo, Kituyi’s University of Nairobi professor, offered him a soft landing as a researcher in his consultancy firm.

While working with Njonjo - in a National Water Master Plan baseline study that took Kituyi to all 45 districts in Kenya except Mandera and Kuria - Kituyi made a Norwegian connection, and ended up spending seven years in Norway starting in 1983.

Stationed at the University of Bergen, Kituyi obtained a diploma in Comparative Production Systems - and fell in love with and married a student of medicine at the same institution, Ling Andersen (later Dr. Ling Kituyi) in 1984.

Kituyi then turned down an earlier scholarship from Georgetown University in the United States - he had gotten it while in Nairobi but opted to defer - and instead pursued an MPhil and PhD in Social Anthropology still at Bergen.

But before setting off for Norway, the stage for Kituyi’s return to Kenya was set.At the tail end of July 1982, Kituyi’s friend Koigi wa Wamwere sent for Kituyi and his cousin Michael Kijana Wamalwa to travel to Nakuru for a little chat.

When Kituyi and Wamalwa arrived, Koigi told them he had picked from the grapevine that a coup was in the offing, and that he wasn’t sure if he would be safe.

With that being said, Koigi informed his two guests that he just wanted his family to know them as his friends, in case the state came after Koigi post-coup.Kituyi went home.

The following day there was an attempted putsch.

"Some of those things about the early ferments of discontent in the country stuck with me," Kituyi says, "and also mark the point where I significantly started to re-engage with processes of resisting oppressive government, an engagement that I was to carry on for the next 40 years."

As it turned out, Kituyi ended up hosting an on-the-run Koigi in Norway not too long after.

And as Koigi was in Kituyi’s place, Kituyi shared a draft manifesto of what he imagined could be used to start mobilizing the Kenyan masses. Koigi took the rough notes, made copies and embarked on a series of dispatches of the same into Kenya.

The Special Branch got wind of this and started arresting Koigi’s addressees in Malaba and Namanga borders, and charged them with sedition.

"The document wasn’t seditious in any way at all," Kituyi says, "it was still a very rough draft."

Kituyi was back in Nairobi in 1989.

Raila had been working with us but when things got very difficult, he had to flee

Upon reconnecting with his teacher Prof. Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, a political cell was quickly born. Working for the Norwegian Agency for International Development (NORAD) at the Norwegian embassy, Kituyi got in-too-deep with the agitators.

"We were a small group of people who were discussing what are the next steps, wondering whether the conditions were ripe for change," Kituyi tells me of the earliest stages of what grew to become the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD).

Among them, and Kituyi won’t mention names, were some who fancied the flowery language of the Russian revolution.

"I even remember some doctrinaires saying the Bolsheviks should now take advantage of the numbers of the Menesheviks to have a critical mass and move the process forward."

We both burst out laughing.

This group comprising Kituyi, Nyong’o, lawyers Paul Muite, Gitobu Imanyara, James Orengo and Pheroze Nowrojee - and sometimes joined by Joe Ager - was what Kituyi considers the core of what became the Young Turks.

Kituyi was at least 10 years younger than the rest.

"Raila had been working with us but when things got very difficult, he had to flee," Kituyi says.

"I hid him in my house before my wife and I drove him to the American embassy. The Americans couldn’t take him in, and so he sneaked out of the country through Uganda, and made his way to Norway where his first stop was my father in-laws house as he was seeking refuge."

In that initial phase, Kituyi says their discussions were centered on whether Kenyans were ready to be led by an intellectually mature but biologically young team as a coalescing point around which to carry out the struggle for the second liberation.

The answer was yes and no.

A decision was made - which in hindsight Kituyi sometimes regrets - to bring in older leaders with whom to build a broader coalition, strong enough to shake the foundations of the powerful Moi state.

"A critical moment of decision making, rightly or wrongly, expanded our ranks from this group called the Young Turks, to now bring in Jaramogi Oging’a Odinga and his inner circle; Masinde Muliro - who came with Musikari Kombo, Michael Kijana Wamalwa and George Kapten," Kituyi says.

"Kenneth Matiba was abroad, but because there was talk of him running we invited his people, represented by the likes of Philip Gachoka, Martin Shikuku and Japhet Shamalla."

By this time, Kenya had severed diplomatic ties with Norway, and Kituyi’s program at NORAD had come to a halt. Kituyi found a job at the Calestous Juma-led African Center for Technology Studies (ACTS).

It was while at ACTS that Kituyi’s dalliance with the Young Turks proved costly. Two board members, former Supreme Court Justice Prof. J.B Ojwang and Prof. Hastings Okoth Ogendo pushed for Kituyi’s resignation, on grounds that he was associating with dissidents.

"Prof. Ojwang and Prof. Ogendo started applying pressure on Calestous that Kituyi is a rebel, an enemy of the government who is dealing with enemies of the government," Kituyi says, insisting he wants this fact recorded, "he should either cut ties with them or leave ACTS."

Kituyi’s stay at ACTS became untenable. He was made to quit, and gave himself to the struggle.

As all of this was unfolding, Kituyi remembers a Young Turks meeting where James Orengo proposed the name FORD, which became a pressure group with Kituyi as its Executive Director.

"I was perhaps the only person with a personal computer at home," Kituyi says.

"We met in all manner of places, including restaurants, and discussed a wide range of issues. But every time we had resolutions, Pheroze, Orengo and myself were tasked with capturing them. But all documents that were reduced to text were done on my computer at home in Mountain View."

At this time, the cracks in FORD were emerging. Jaramogi and Matiba were pulling in different directions, with Muliro making an effort to narrow the rift between the duo.

"A lot of people don’t understand just how averse Muliro was to controversy," Kituyi says.

"We even had a joke as the Young Turks that whenever there was a hard decision to be made or some of us hotblooded folk wanted to escalate things politically, Muliro was to be found doing a pilgrimage to the Holy Family Basilica, to meditate and pray for a non-controversial breakthrough with Cardinal Maurice Otunga."

Unfortunately, Muliro died before Jaramogi and Matiba closed ranks. Thereafter, two splinter groups emerged, domiciled at Jaramogi’s Agip House and Matiba’s Muthithi House offices.

The factions became known as FORD-Agip and FORD-Muthithi, before FORD-Agip became FORD-Kenya and FORD-Muthithi morphed into FORD-Asili.

All the Young Turks, without exception, sided with Jaramogi and went into what became FORD-Kenya.

I ask Kituyi why the Young Turks followed Jaramogi en masse.

"Neither of them (Jaramogi and Matiba) was saying all the things we wanted to hear," Kituyi says.

"But of the two, Jaramogi was more willing to listen to us and be more accommodative. But on Matiba’s side, our impression was that they were not interested in listening to ideas but were more fascinated about building a movement around a personality."

And with that, FORD-Kenya and FORD-Asili hanged separately during the 1992 general election.

At the time, a FORD-Kenya rally was incomplete unless Kituyi sang. And it wasn’t just any ballads.

Kituyi had specialized in particular Daudi Kabaka oldies, which he made a habit of corrupting then perfecting.

He would swap the original lyrics with his own satirical compositions - designed to ridicule President Daniel arap Moi and his yes men - then master their rhythms and tempo, delivering them with such effortlessness as if he was Daudi Kabaka’s body double.

Mukhisa calls this jigging during the FORD-Kenya rallies building electricity.

"We were intellectually the finished product," Kituyi says of their prowess and antics.

"But we also knew delivery was important. And so we tried to find the best ways to engage the crowds."

And yet for Kituyi, there was more to the singing than met the eye.

"I had a battered Isuzu Trooper, which had no music, nothing," Kituyi says, "and so whenever I drove from Nairobi to Bungoma, I kept myself from dozing off by improvising new lyrics and singing Daudi Kabaka classics. I would then try the songs out on crowds to see if they worked."

State fragility often challenges security and development in nations.

— Debunk Media (@debunkdotmedia) October 20, 2021

Having experienced the brutal effects of a failed state, Mukhisa Kituyi lives with the constant reminder that we ought to guard the peace we (Kenya) have jealously.

Read the story ➡️ https://t.co/ir9AQCgtJf pic.twitter.com/mHIwys0Krp

For other (unnamed for now) Young Turks, getting Kiswahili tutors became necessary.

Having the ability to fluently work crowds in both English and Kiswahili was mandatory.

In Kimilili Constituency, Kituyi was facing off with Elijah Wasike Mwangale, a powerful KANU minister and a man of means. Other than his jalopy of an Isuzu Trooper, Kituyi had a little esimba, the one he built while a student at the University of Nairobi.

There was not much to write home materially about him. But Kituyi tells me the Bukusu had decided.

It was chibili chibili across Bungoma, chibili being two, signifying FORD-Kenya’s two finger salute.

Kituyi made his parliamentary debut at 36, becoming opposition Chief Whip.

"It wasn’t out of any of my doing - my brilliance, my ideology, or my oratory prowess," Kituyi says. "I owe it to the moment and the movement, and can’t take credit that I did anything unique other than stand up in courage to be counted at a time when Kenya needed us."

But after everything is said and done about that epoch, a question and a personality linger in Kituyi’s mind.

The question is, were the Young Turks right to rope in the older leaders, and the persona is Jaramogi Oginga Oding’a, a man who afforded Kituyi a level of rare trust.

"I think that one of the betrayals we made for the struggle in this country is that when the country was warming up to what we stood for," Kituyi reflects, "we kind of compromised by surrendering to preexisting factions within the political landscape. Matiba and Jaramogi each represented certain continuities of battles of the yesteryears, which were not ours."

Kituyi remembers that it was Raila Odinga, more than anyone else, who urged the Young Turks to venture on their own and chart their destiny - including away from his own father.

Paul Muite too entertained this idea, but the rest of the Young Turks seemed to prefer costly pragmatism. But as they say, hindsight is 20/20.

I ask Kituyi how Jaramogi came to trust him.

"Raila Odinga and Anyang’ Nyong’o cultivated that bond between me and Jaramogi," Kituyi says, "in a way that when we met I could tell him some of the things I thought were useful for him to do. And he accepted. And already very early when we started doing press releases, my owning the first computer in the group meant I prepared some of his speeches, and he seemed happy with what I brought him. In acknowledgement of this, he opened himself up to me."

Kituyi tells me that over time, Jaramogi became very candid with a small group of them, up to his death. Kituyi, Orengo and Nyong’o - and sometimes Muite - had also become very close.

"He told us some very intimate things," Kituyi says, "which have remained off the record but which give us a sense of who we are and what were the pitfalls in Jaramogi’s own reckoning."

I ask Kituyi a question; does the secrecy shrouding these conversations feel like there was an oath of silence?

"Almost," Kituyi says without hesitation.

"The last meeting Kijana Wamalwa, Gitobu Imanyara, Paul Muite, James Orengo, Anyang’ Nyong’o, George Kapten and myself had with Jaramogi in his hotel room in Mombasa a week before he died," Kituyi says, "he told us things knowing he was about to die. And he told us he had called us purposefully, and told us very profound things which we’ve never shared with the Kenyan public. It was a thank you and a goodbye meeting as he told us his body clock was slowing down. He thanked us for our service and for making him feel and be young again."

Kituyi won’t say anything more than that.

Read part 3 this evening in the Star, Mgazeti.com and Debunk Media. This article is a collaboration between the Star and Debunk Media whose Editor-In-Chief is Isaac Otidi Amuke