Part 1: Learning law isn't for money

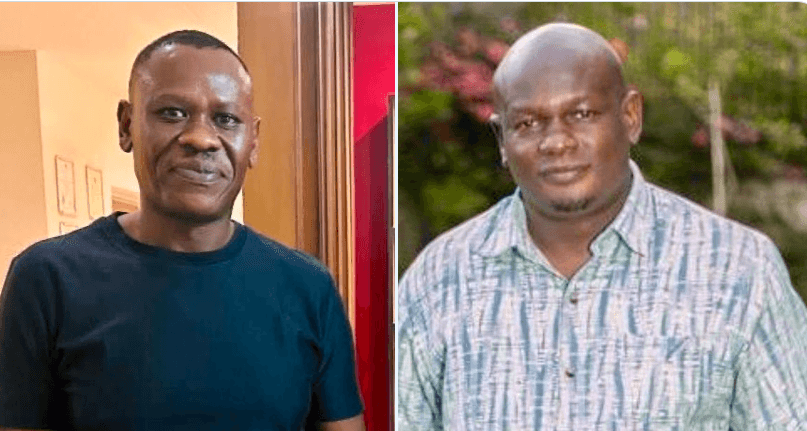

There is a story Makueni Governor Prof Kivutha Kibwana’s wife Nazi Kivutha doesn’t like because she says it is deeply embarrassing. And yet when I meet Kibwana at his hideaway private office in Nairobi’s Kileleshwa estate, the governor laughs and shares the tale. In true Kibwana style, the office is furnished austerely, suggesting that if Kibwana had the option of no office, he would seize it.

The nondescript building, a refurbished old bungalow in an expansive compound, bears no sign it could be a governor's office.

When Kibwana was enrolling at Machakos School for his O Levels, the only thing the 13-year-old aspired to was a job so he could afford food. It was that simple.

Born into a family of 26 children — Kibwana’s mother had 13 while his stepmother had 16 offspring — Kibwana spent his early years first at his grandfather’s home then later at his aunt’s. He went to school in both places; food was still hard to come by.

While at his grandfather’s Kibwana accidentally enrolled for school, out of boredom and curiosity.

"My grandfather’s baby brother and my aunt were attending a nearby school," Kibwana says, "so I followed them. No one imagined I was learning anything but I was enjoying classes and learning a lot. Unfortunately, the school had only Classes 1 and 2, meaning after Class 2, the syllabus was completed.

They circled back and started over. "Fortunately, that's when I moved to my aunt's," Kibwana says.

His aunt was a widow with no means of support, so the six-year-old used to carry boiled maize and vegetables to school for lunch.

At school he sat with children from well-off families who carried better food and tastier dishes, which at first they shared with him. Then they decided he wasn't worth their generosity since his own food was terrible.

Kibwana was banished and cried.

"That day," Kibwana says, "I vowed to study hard so I could afford food."

Kibwana never told his parents he was suffering lest they withdrew him from school. Much as he missed his parents and siblings, Kibwana made up for this by attending Friday and Saturday night folklore sessions in the village. He developed his love for poetry and theatre. These sessions proved useful later when he started writing in Kikamba.

And so Machakos School was a utopia for Kibwana. There was plenty of food, and all he needed to do was show up at the dining hall. It was here that he wore his first pair of shoes and for the first time met people from all over Kenya.

This is where the story Nazi Kivuta detests comes in.

"In my early days at school," Kibwana says, "one day I went to the toilet for he big job. I kept looking over my shoulder and seeing a hanging chain. With a young man's curiosity, I pulled the chain to see what would happen, only for a loud noise to descend on the room.

"I dashed out even before I had buttoned up properly, afraid I had broken something and was about to get into serious trouble."

He waited for his crime to be discovered but nothing happened. Then he got up the courage to ask a Form 4 what pulling the toilet chain meant.

The response, "Don't be a fool. You simply flushed the toilet."

The toilet mortification, Kibwana says, was closely related to another misdemeanor in the Physics lab. An adventurous Kibwana was messing around with a socket, only for his British teacher to rush over and shout "You stupid boy, do you want to kill yourself?"

From that point onwards, Physics and Kibwana became like water and electricity.

But aside from these early mishaps, Kibwana generally enjoyed his time at Machakos School. During his A Levels, Kibwana opted to study the Arts, keen on studying Literature at the university. He had written plays and acted at the National Drama Festivals.

Much as he didn’t play any sports actively, Kibwana remembers participating in a 60km walk as a Form 1, rom Machakos School to City Hall in Nairobi to raise funds for the school swimming pool. Kibwana was the last arrival and was gifted Sh10.

When Kivutha Kibwana arrived at the University of Nairobi in 1973, aged 19, 26-year-old future Chief Justice Emeritus Dr Willy Mutunga was about to be hired to teach Commercial Law. By the time Mutunga embarked on his lectures, Kibwana was in his second year.

He taught and mentored Kibwana.

"Back then he was simply known as John Mike, John being his baptism and Michael his confirmation name in the Roman Catholic denomination," Mutunga says when I ask about his earliest memories of Kibwana

‘‘He was one of the brilliant students, and I also knew he spent a lot of time with the radicals in the Literature Department, joining their Free Traveling Theatre project that took students all over the country performing plays. All plays, without exception, had radical messages.’’

At the Literature Department were the likes of Okot p’Bitek and Ngugi wa Thiong'o.

"Those days, much as I was a student of law," Kibwana says, "I could pick which other lectures I wanted to attend just for my own general knowledge. Classes were small and I would attend Okot p’Bitek's literature lectures, and those of many others.’’

For Kibwana, it was all a thirst for knowledge.

Mutunga doesn’t shy away from how he deliberately taught his students, saying that as a graduate of the University of Dar es Salaam - which Mutunga calls the Mecca of revolutionary university education - he had mastered teaching methods that valued the students' intellect, embracing history, socio-economics, culture and politics.

"Kibwana was one of the key adherents of this approach given his practical multidisciplinary pursuits at the university," Mutunga says, "and if I played any role in his academic and other progression, then it is that he and others became brilliant disciples of the radical teaching method of the law." Kibwana concurs.

"There had been conservative professors who taught you law so you could became a big time lawyer, make a lot of money and have a big name," Kibwana says.

"But then came a new breed of professors, people like Mutunga, who taught us that education can be used to serve the people, and in me they found fertile soil to receive knowledge that would help me actualise some things that I thought were right as a young person. So yes, whether it is Willy Mutunga or Ngugi wa Thiongo, those of a reformist and progressive bent - they were of course called radical, socialists and even communists - they influenced my generation in a major way."

And yet, for Kibwana, these ideals went deeper than what his professors taught him.

"For me, it wasn’t theoretical radicalism," Kibwana says. "It was something borne from my lived life experiences, and maybe that is why it is usually consistent, because it is something from childhood, something from boyhood, and it is something in maturity."

Kibwana tells me of how while in primary school, whenever his aunt went to the shopping centre in Emali, all she came back with were bones. Unfortunately, Kibwana says, he never got to ask her whether she was given the bones for free or paid for them.

This is why whenever a goat died in the village, Kibwana and others would get excited since that was their opportunity to eat real meat, a rare commodity.

"Tied to this was my religious teachings, to love my neighbour as I love myself, and lessons from Akamba folklore where the bad guys always ended up in some misfortune or other,"Kibwana says. Western religion, African folklore and radical intellectualism had intersected in Kibwana.

But beyond listening to his professors, Kibwana was also a frontline student activist.

"I was minister for information and propaganda in Oluoch Obura’s government," Kibwana says with a chuckle. "W had unusual names for our roles, but those days students were really unhappy with the Kenyatta government.

"Our heroes were people like JM Kariuki and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who remain my heroes to date. It was a difficult terrain".

On completing his undergraduate law degree, Kibwana earned two postgraduate scholarships, one from UoN and one from the University of London.

Kibwana chose London.

'The thing about these universities is that you got a first-class education," Kibwana says of his time abroad. "Teachers were sent on annual sabbaticals in industry and government to learn what was really happening. We also had 24-hour libraries and we mingled with students from all over the world." To Kibwana, it was all books.

After a year in London, Kibwana returned to Kenya and taught at the University of Nairobi. He was only aged 23 and hadn’t attended the Kenya School of Law. Its principal, British barrister Tudor Jackson, wasn’t eager to have Kibwana at the institution following his history of student activism.

But Kibwana was didn't care. His entire academic life was ahead of him, he would finally work alongside his mentors.

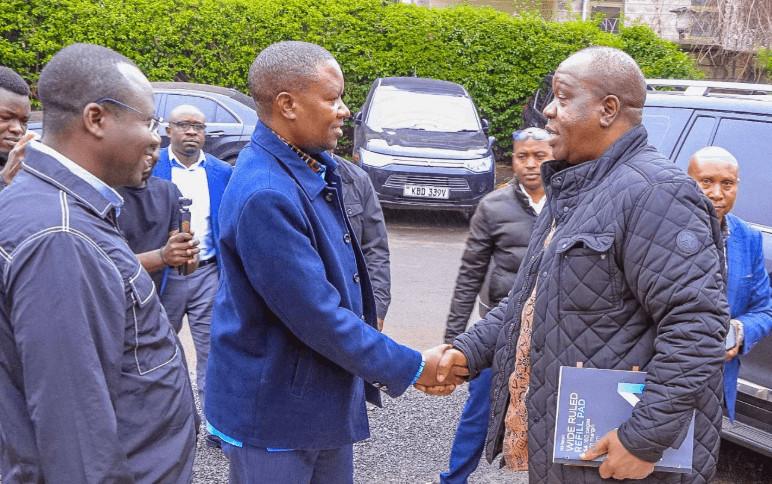

"Kibwana and I built a comradeship when he came back from London and joined the Faculty of Law as a colleague and comrade,"Mutunga says.

"Having him in the radical and progressive wing of the faculty and the university was important. Our numbers were small (initially there were four of us who I could count as radical teachers and thinkers—the late Dr Oki Ooko Ombaka, Professor SBO Gutto, and Professor Robert Martin, a Canadian scholar).

"The issue of teaching approach came up and we had a retreat to discuss it. This was a serious battle-struggle of ideas in the teaching of law. Our group won, courtesy of the moderates in the faculty teaming up with the radicals and the radical student representatives in the faculty board."

What does Mutunga remember most about Kibwana?

"One visit stands out by Kibwana and his wife Nazi to Industrial Area Remand Prison. I was held in ustody for two months facing sedition charges," he says.

"These charges were later dropped and I was detained without trial for 14 months. Kibwana was the only colleague from the faculty to visit me although the other progressive colleagues attended court sessions. Nazi was pregnant with Ngumbau. The stench in the prison was too much for her and she fainted. I have never forgotten the act of courage and humanity by the two of them."

It wasn’t long before Kibwana was off to Harvard University for his second master's degree.

Read part 2 tomorrow in the Star, Mgazeti.com and Debunk Media. This article is a collaboration between the Star and Debunk Media whose Editor-In-Chief is Isaac Otidi Amuke

(Edited by V. Graham)