A visitor to Kenya today would be forgiven for thinking it is Christmas. Towns are virtually empty, families are home.

But lingering posters and billboards show it is the eerie aftermath of elections and not the festive season.

Kenyans are constantly checking social and mainstream media and trying to make sense of the mixed signals on who could be their next President.

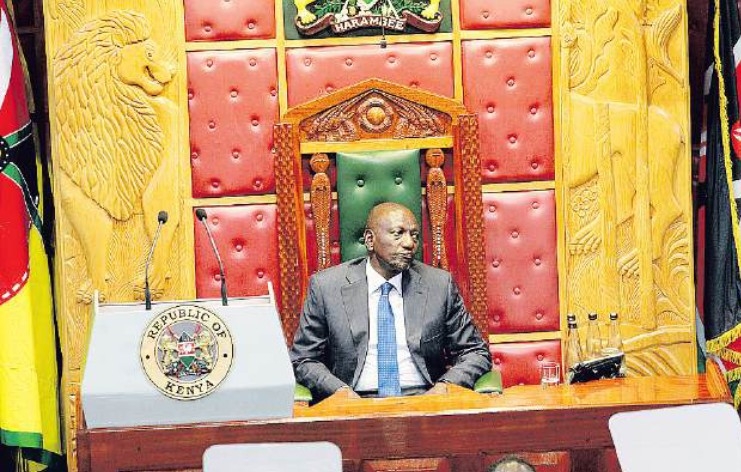

Deputy President William Ruto and Opposition leader Raila Odinga are neck-and-neck.

The electoral agency previously gave a running tally of results but has now left the media to take the initiative.

Chided for not “opening the server” in the past, IEBC granted universal access to the results on its website this time.

But that means results from more than 46,000 polling stations, yielding incremental tallies from a disjointed and under-resourced media.

Kenyans voted on Tuesday but the week is ending with the winner still a mystery, a delay foreseen by Kenya Editors Guild president Churchill Otieno.

“IEBC won’t declare the results until they get the manual forms,” he said at a forum with telcos ahead of the polls, terming it a step back to 2007.

“This opens the door to all sorts of mischief.”

2007 is indelibly marked in the consciousness of Kenya, hitherto a beacon of democracy in East Africa, thanks to the near-civil war that erupted.

The losing incumbent was suddenly declared the winner and sworn in at night, sparking tribal attacks that left more than 1,100 people dead and 600,000 internally displaced.

Critics say dredging up the violence in every election is scaremongering, but it has not been all rosy since then. 100 people died in clashes in 2017.

Still, Kenya has made great strides. Electoral commissions have been disbanded and reformed.

Security is enhanced before elections, with hotspots shifting depending on political alliances.

And network coverage has increased up to 98 per cent, enabling quick transmission of results.

“Many people ask us, ‘Can your employees interfere with the election?’” Peter Ndegwa, CEO of the leading telco Safaricom, said.

“No. Our role is [to be] a pipe for transmitting results to tallying centres. We don’t know and don’t influence the content.”

IEBC is erring on the side of caution after the Supreme Court overturned the last presidential election over irregularities.

The decision to declare results despite a breakdown in the results-transmission system was singled out by the Carter Centre as leading to legitimate questions about the accuracy of the results.

“It critically undermined the transparency of the tallying process and severely hindered verification efforts by parties and independent observers,” the centre’s report said.

So IEBC chairman Wafula Chebukati is taking his time this round.

“The issue of declaring results, that will not happen today,” he told reporters on Wednesday. “We have seven days to do that.”

He said the commission was holding off on tallying until it starts receiving the original form 34As and 34Bs from returning officers.

The forms started streaming in later on Wednesday, with some having to be flown in from remote corners of the country.

Still, the sheer volume and validation process means it will take a while, up until Saturday by one projection, even if the media finishes tallying sooner.

It is this prolonged wait for closure that awakens the ghosts of 2007.

Elections are otherwise usually peaceful and, save for some technical hitches, proceed quite smoothly.

Tensions rise with each day of counting and tallying of results. Businesses closed for the elections are yet to reopen. A wait-and-see approach is keeping the country at a standstill.

The last election gave hope that Kenya is maturing as a democracy. Rather than call for protests, the losing side went to court.

Telcos suspected of interfering with the election, officials accused of bungling it — all was dealt with in the Supreme Court, which showed historic independence in its judgement.

But the losing side boycotted the re-run, depriving the commission of a chance to redeem itself.

Misgivings preceded this election as well. Up until the eleventh hour, there were disputes; for instance, on the use of a manual register as a backup in case of technology failure.

It is not just politicians complaining. A Sauti ya Mwananchi survey in March found that only four out of 10 Kenyans believed the IEBC was capable of conducting credible polls.

The commission registered 1 million new voters out of a target of 4.5 million despite multiple extensions.

That apathy carried over to the election. The 14 million Kenyans who voted was a turnout of 65 per cent, down from nearly 80 per cent in 2017.

It baffled politicians spending millions on campaigns and seeing massive crowds at rallies.

Those who did not vote say they are disillusioned with the choices, if not skeptical of the promises to fight corruption and tame the cost of living.

Still, everyone is affected by the fear of violence. And the tightness of the race means whichever way it goes, half the country will be disappointed.

Rather than light at the end of the tunnel, a run-off is looming large, with the threshold of 50 per cent plus one vote eluding contenders.

The electoral commission should find a way to fast-track the outcome; otherwise, trust in elections will remain low.

The media ought to coordinate its tallying, as audiences are now treated to varying results depending on where each outlet has reached, breeding suspicion of rigging.

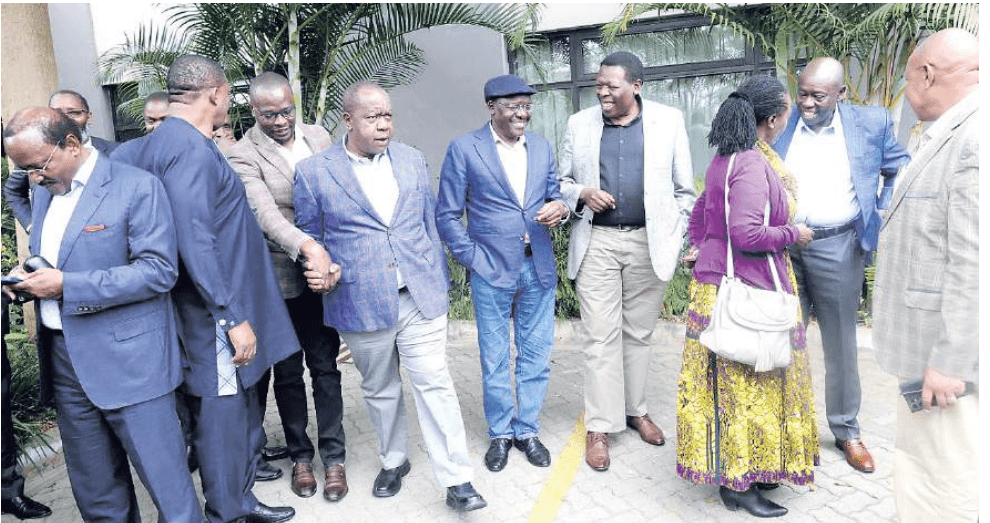

And the main contenders, Ruto and Raila, would do well to emulate opponents in lower seats whose results are out, even if not officially.

A growing number has conceded and congratulated the winner.

In case of any issues, the courts can decide.

For, much as Kenyans have their biases, the prevailing sentiment is: “Whoever wins, let there be peace.”