I felt a piercing pain that paralysed my body. I thought I was going to die but luckily my husband, Laban Keben, was nearby and heard me screaming. He rushed over to rescue me

On August 9, 2021, 13-year-old Cherop Samut bid her class teacher farewell and promised to report to school early the next day dressed in a clean uniform.

At 3pm the Grade 3 pupil and her two friends went to Lake Baringo to wash clothes and bathe.

It was there that she was attacked by a crocodile.

The animal emerged from the water, grabbed Cherop's leg and started pulling her towards the lake.

Her two friends tried to pull her but the animal was too strong and they watched helplessly as the crocodile swam away with Cherop, said Samuel Korir, Katuwit Primary School head teacher.

“I am yet to believe my firstborn daughter is dead and gone,” says her mother, Toyoi Lokodong, 37.

“Since then, I have been camping at the flooded lake, watching as the wind blows the water just in case remains of my deceased appear on the shore, so I can bury her and get closure.”

Since mid last year, Rift Valley lakes have doubled in size following heavy rains, pushing crocodiles and hippos closer to residents.

Lokodong's family, for instance, previously lived in Chesesoi village, a kilometre away from their current location, Katuwit.

But the area is now under water and the family had no choice but to move.

Lokodong found shoulder bones that were taken to the Government Chemist for tests but the family is yet to be told whether they belong to Cherop.

Her husband, David Sangut has made frantic but futile efforts to get the bones for burial and compensation.

Another loss

As the family was still coming to terms with losing one child, death snatched another from them.

Their two-year-old son died of malnutrition-related illness in February this year.

“Before losing my daughter and son I used to do menial jobs like fetching water, collecting and selling firewood to feed my family but I dropped everything to focus on searching for the body of my beloved girl,” Lokodong says.

He [Reuben Chelimo, 65] threw a stone to scare away the animal and went ahead to cast his net to fish, little did he realise the hippo's calf was standing near him

She had no milk to feed the child as she was starving.

“There is no food left in the house. I am so hungry. I would offer my child empty breasts to suckle and supplement that with water,” she says.

The family lives in a shack in Katuwit village at the edge of the flooded Lake Baringo.

Amputated

A few kilometres away in Meisori village, Baringo South, lives Winnie Keben, 28, who lost her left leg in a crocodile attack a few years ago.

The place where her family home originally stood is now seven kilometres inside the lake.

Winnie was bending to fetch water from the lake at 5pm when a crocodile jumped out, grabbed her leg and pulled her into the water.

"I felt a piercing pain that paralysed my body. I thought I was going to die but luckily my husband, Laban Keben, was nearby and heard me screaming. He rushed over to rescue me," she says.

During the struggle, the animal let go of her leg and grabbed his leg. "He screamed and a passerby heard him and came to his rescue," Winnie says.

The two were taken to Baringo County Referral Hospital in Kabarnet. Winnie was referred Nakuru General Hospital, where doctors amputated her leg.

Life has changed drastically since the attack.

Before, Winnie worked as a casual labourer on farms at the Perkerra irrigation scheme to help meet the family's financial needs.

"Now I can't help. I just stay at home waiting for my husband, a casual labourer, to go out alone, hustle and feed the family," she says.

The couple has six children and together they live in a mud-walled, grass-thatched house.

They are struggling to feed and clothe the children, and pay their school fees.

Listen to this story via Podcast

Cherop and Winnie are some of the victims of intense human-wildlife conflict in the area, especially with crocodiles and hippos.

Appeals to the government for compensation go unheard

Reuben Chelimo, 65, was fishing in the shallow waters at 1pm on September 10, when he spotted a hippo.

“He threw a stone to scare away the animal and went ahead to cast his net to fish, little did he realise the hippo's calf was standing near him," Peter Chepkwony says.

The furious mother hippo chased him and attacked him, killing him.

Fabregas Kemboi, 10, was killed by a hippo in February 2019. He and his friends had gone to the lake to bathe and fetch water when he was attacked.

Two weeks later his hand was recovered and his parents, Winnie Chebii and David Kiplagat, buried it.

Instead of people staying away from these dangerous animals, they build their houses near conservation or protected areas, fish and roam on the lakeshores, exposing their lives to danger

Douglas Keitany, 42, was out fishing on Lake 94 when his boat was overturned and he was eaten by a crocodile in July last year.

Braving attacks

Faced with few prospects in life, the residents have no option but to learn to live with the deadly animals.

“Life here has been reduced to survival of the fittest,” says fishmonger Sarah Koech.

She says sometimes they see people and animals being attacked but cannot help.

She works on the shore of the lake with other women, offloading and sorting fish for sale.

Joshua Chepsergon of Lake Baringo Water Rescue and Safety International says many people have been attacked and killed by crocodiles and hippos.

Livestock too are killed daily, hurting livelihoods, he adds

The notorious shores include Komolion Island, Kampi ya Samaki, Loruk, Ilchamus and Island camp.

"There is no place to live in the flooded Lake Baringo after the water pushed crocodiles and hippos closer to people's houses, schools and farms," he says.

Chepsergon urges the government to provide a solution—either move the animals or relocate the residents.

“The victims should also be compensated and measures put in place to curb or minimise the attacks,” he says.

Chepsergon says there's need to dispose of the rapidly breeding crocodiles.

“A single crocodile lays and hatches up to 60 eggs per year and I guess they have really multiplied,” he says.

Baringo Kenya Wildlife Services warden David Cheruiyot blames the rising human-wildlife conflict majorly on human encroachment.

"Instead of people staying away from these dangerous animals, they build their houses near conservation or protected areas, fish and roam on the lakeshores, exposing their lives to danger," he says.

Cheruiyot says the government will only compensate genuine cases, and only after proper investigation and provision of sufficient evidence of the occurrence.

Intervention

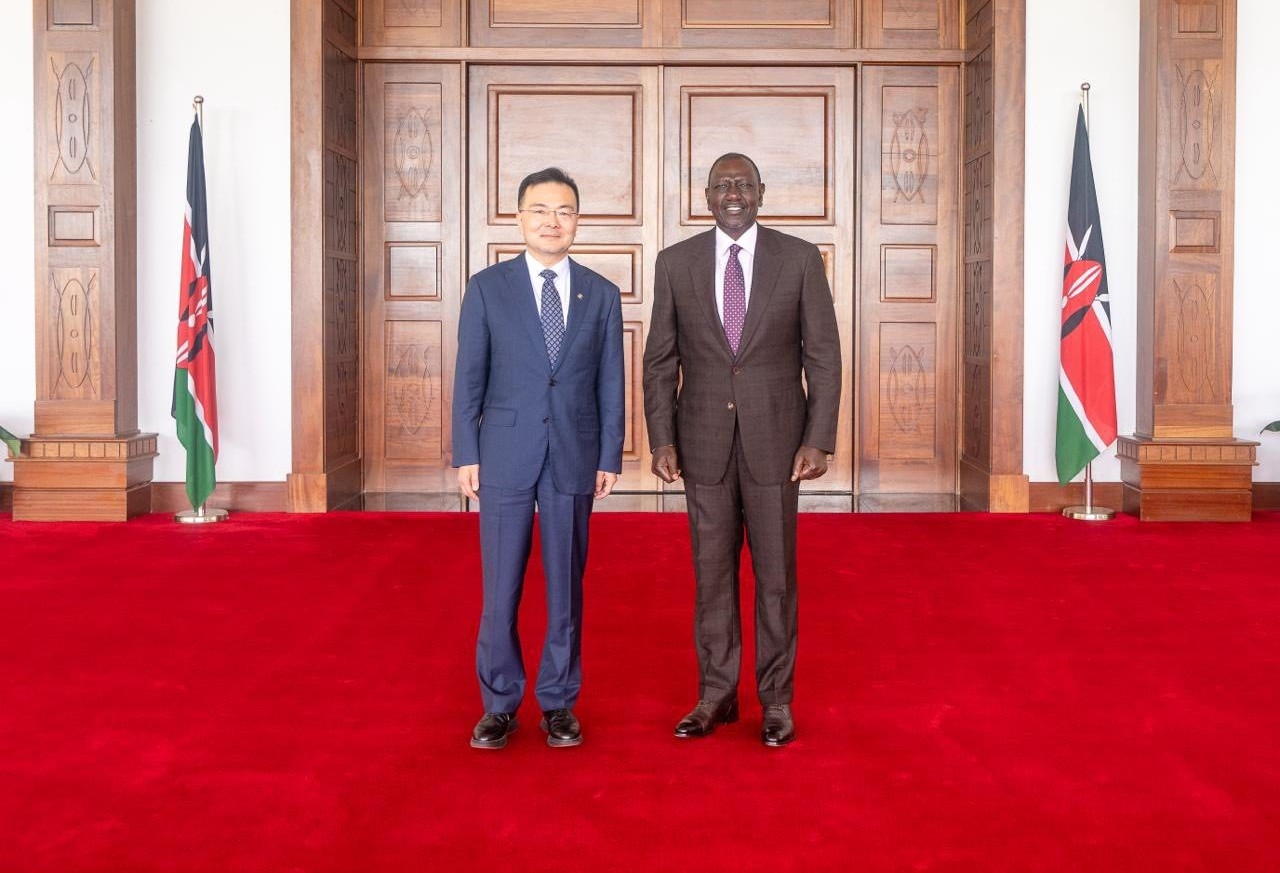

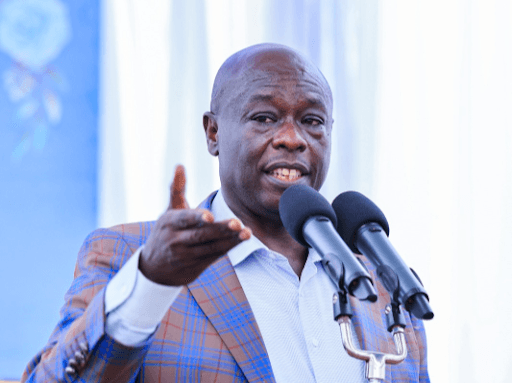

Baringo Governor Benjamin Cheboi has called for the deployment of more Kenya Fisheries Constable Guards to help in rescue operations.

He has also urged the communities living on lakeshores to exercise caution.

Last year the government, through the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife, launched Sh500 million compensation for victims of human-wildlife conflict.

Then Tourism CS Najib Balala commissioned the payout at Kampi ya Samaki in Baringo in June.

He said the payments would clear a backlog of claims lodged between 2014 and 2021.

“We have further allocated Sh600 million for compensation in the coming financial year, 2021-22,” Balala said.

The CS, however, decried the low allocation, saying it was not adequate and stakeholders, including MPs, should think outside the box to raise money for the claims, which stood at Sh3.1 billion.

This story was produced by the Star Publications in partnership with WAN-IFRA Women in News Social Impact Reporting Initiative

Edited by Josephine M. Mayuya