Orgies conjure in our imagination the world of Greek and Roman Antiquity, thanks to more or less titillating films portraying debauched emperors, or maybe specifically Fellini’s Satyricon. The term is also used today to signify all sorts of excess. For us, the orgy stands for the ultimate celebration of the pleasures of the flesh, in an ancient world free from moral constraint. But what were they like in reality?

From orgia to orgies

The word comes to us from the Greek orgia. This denotes rites practised in honour of gods such as Dionysus, whose cult celebrates the regeneration of nature. It concerns so-called mystery cults – that’s to say, those limited to initiates, men and women, previously sworn to not divulge their secrets.

The term orgia suggests passion and thrill. Orgiastic rites – little known about because of the mystery surrounding them – could involve brandishing objects of a sexual form, in the course of ecstatic and violent displays which aimed to reach a state of collective stupor.

But it was only after 1800, over the course of the 19th century and notably in French literature, that the orgy took the meaning of group sexual practices, most often associated with excesses of alcohol and food. Flaubert conceives in his tale Smarh, written in 1839, “A night-time festivity, an orgy full of naked women, beautiful like Venus”.

Prostitutes… and fish

An orgy, properly defined, is not, however, a modern invention. Banquets mixing gastronomy and erotic delight are familiar in classical texts. Thus in the 4th century BC, the Greek orator Aeschines, in his speech against Timarchus, accuses his enemy of having surrendered to “the most shameful vices” and “everything which a free nobleman shouldn’t let himself get subsumed by”.

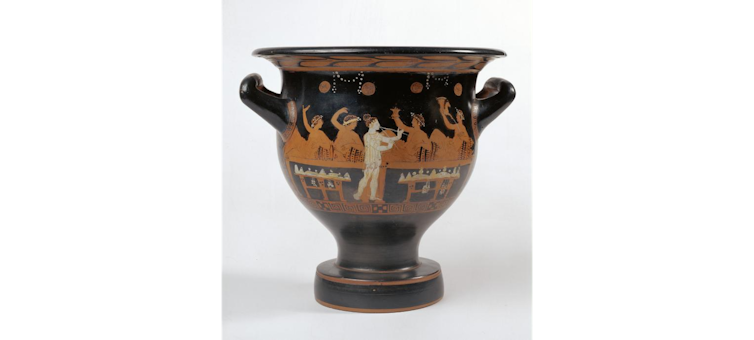

What were these forbidden pleasures? Timarchus invites home flute players and other reprobate women, and dines with them. We figure out that the flautists weren’t there simply as artists, picked solely for their musical talent, but young prostitutes primed to satisfy diners’ sexual demands.

As well as picking up courtesans, eating very expensive fish was a detail particularly noted by 4th century BC orators. Demosthenes links these two aspects of debauchery together in his False Embassy oration.

In 346 BC, the city of Athens had sent ambassadors to King Philip II of Macedon, who was threatening Greece with his troops. But the ruler had corrupted some of the Athenian ambassadors, to the point that they supported his imperial ambitions.

One of these envoys, who had been bought by the Macedonian king, is accused by Demosthenes of squandering his ill-gotten gains on “prostitutes and fish”. A double dose of gluttony, both carnivorous and carnal.

Roman debauches

Roman historians also described sumptuous feasts, pairing sex and food. In the decade 89-80BC, the tyrant Sylla was the first Roman political leader to convene erotic drinking parties. He would have taken the concept from the Greek East, where he had been waging a military campaign. Sylla caroused until the morning with comic actors, musicians and mime artists, Plutarch writes (Life of Sylla, 36).

Erotic dancing was one of the courtesan’s additional skills, and likewise it wasn’t rare that prostitutes turned to mime artistry. They writhed while sometimes simulating sex acts.

The Latin historian Suetonius portrays Tiberius as the archetypal debauched Emperor. In his palace at Capri, he staged daringly pornographic spectacles. He had enlisted a company of young actors who before his very eyes engaged in sex acts called spintriae – a Latin term, very likely from the Greek sphinkter (anus), suggesting a daisy chain (Life of Tiberius, 43)

Caligula, Tiberius’s successor, would, according to Suetonius, sleep with his sisters, in view of his guests (Life of Caligula, 24). Incestuous and exhibitionist, he thus broke two Roman taboos at once. He would also display his wife Caesonia on horseback, dressed as a warrior, or alternatively completely nude. A willing accomplice in her husband’s foibles, the Empress would have particularly enjoyed these special sessions, because she was, Suetonius claims, “lost to debauchery and vice” (Life of Caligula, 25).

Some 20 years later, the Emperor Nero “made his parties last from midday to midnight,” Suetonius writes (Life of Nero, 27). All the senses needed to be sated in the course of these long feasts. They were symphonies of food, music and pliant bodies – to look at or to ravish – while slaves made flowers rain down from the ceiling and filled the air with perfume.

During a feast of the Emperor Elagabal in around AD 220, guests were suffocated to death “and were unable to break free” if one believes the author of the Historia Augusta (Life of Antoninus Heliogabalus).

But these decadent banquets were no more commonplace during the Roman Empire than they are today. There’s no doubt about the meaning of these descriptions of orgies by ancient authors. There’s always a moral purpose: condemn “debauchery”, in the name of moderation and temperance.

Christian denunication

The Christianisation of the Roman Empire only reinforced this moral perspective. There’s a good example in St. Augustine’s work (16th Sermon, on the beheading of John the Baptist).

The portrayal of Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee’s banquet, with food piled high, underlines the gluttony of the guests. Augustine adds a depravity which is entirely Satan’s work. Herod asks his great-niece Salome to dance for him. The baleful young woman, after revealing her breasts in the course of her frenetic dancing, demands in return for her favour the head of John the Baptist, served on a platter.

From Rome to Babylon

Breaking with classical texts, Damien Chazelle’s film Babylon confronts the viewer with a huge orgy scene without casting clear moral judgement over it.

That’s perhaps one reason that reactions have been strongly polarised, between detractors calling it an outrageous film, and admirers hailing a miraculous “visual orgy”.

Translation from French to English by Joshua Neicho.![]()

Christian-Georges Schwentzel, Professeur d'histoire ancienne, Université de Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

© The Star 2024. All rights reserved

© The Star 2024. All rights reserved