Kenya on Tuesday, marked 45 years since the death of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

This will be the third time that there are no public commemorations as had been the tradition.

Kenyatta, who was Kenya’s first President died on August 22, 1978, at 3:30 am in his sleep at State House, Mombasa.

His mausoleum and statue at Parliament Buildings is a landmark in Nairobi and Kenya and symbolic of the expression 'Here lies a man that walked the country like a colossus.'

A mausoleum is a stately or impressive building housing a tomb.

In 2019, the Kenyatta family through Retired President Uhuru Kenyatta, announced that going forward, the commemoration of the death of Kenya’s first president would be a private affair.

He said the agreement was reached after consultations with the entire Kenyatta family.

"As President, I have consulted with the family of Mzee Kenyatta. We have agreed together that this is going to be the last celebration of 41 years of Mzee in this manner," Uhuru said then.

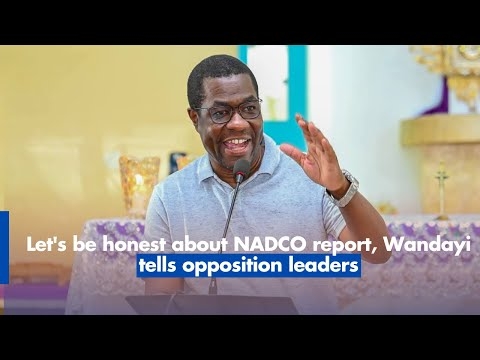

This was during the memorial service that was held at the Holy Family Basilica, Nairobi.

Previously, Kenyatta’s memorial ceremonies were marked with a church service attended by the Kenyatta family led by First Lady Mama Ngina Kenyatta, the President, and senior government officials.

Also, there was the laying of the wreath ceremony that was conducted by the Kenya Defence Forces, including a military parade.

The military has always guarded the mausoleum which, ironically, was never opened to the public and is considered to be Mzee Kenyatta’s resting place.

However, visiting Heads of state up to date choose to go pay their last respect at the mausoleum if they wish so.

History

Despite Kenyatta's death leaving a whole nation shell-shocked, there were signs that his health was waning and that he would not be able to hold on to power any longer.

In 1968, he suffered a stroke prompting conversations among local politicians and the British government about possible successors.

A 2016 article by Poppy Cullen in the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History reveals that the British government had developed a contingency plan for Kenyatta Sr's state funeral as early as 1968.

"The plan covered a range of specific details including the timing and location of the funeral, the coffin, transport, lying-in-state, guests and burial," Cullen reveals.

Cullen adds that Bruce McKenzie - the only European minister in Jomo's cabinet - was tasked with the responsibility of presenting this plan to then Vice President Daniel Arap Moi, Minister for Defence Njoroge Mungai, and Attorney General Charles Njonjo.

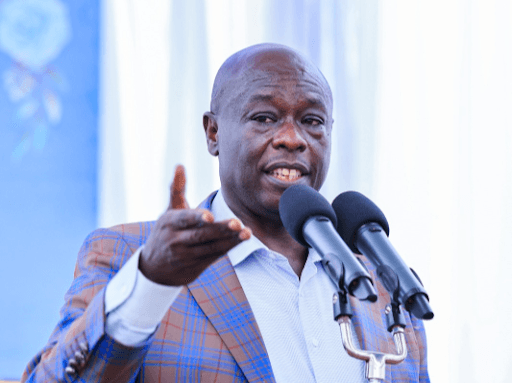

On the local political scene, there was a spirited campaign by hardliners loyal to President Kenyatta to prevent then Moi from ascending to power.

Known as the Change the Constitution Movement, the group led by Kihika Kimani and Njenga Karume, campaigned for a constitutional amendment that would bar the vice president from succeeding the president in case the latter was incapacitated.

However, Njonjo - determined to oversee a peaceful and rightful transfer of power from Kenyatta to Moi - warned that it was treason to imagine the death of a sitting president.

Upon Kenyatta's demise, however, the contingency plan developed by Britain was amended because it had not been properly communicated to many within Kenyan government circles.

Whereas the initial plan was to engage an embalmer from Kenyons Ltd in England, this was scrapped in favour of Frank Clayton, a Kenyan-based English embalmer with extensive experience.

An embalmer is a person whose job is to use chemicals to prevent a dead body from decaying.

"Frank Clayton had been superintendent of eight cemeteries in Nairobi for 20 years until 1968. As Clayton was not himself an embalmer, he turned to a colleague, Allan Sinclair, to assist," Cullen says.

Sinclair almost never made it to Kenya in time for lack of a passport.

Oblivious of earlier plans to secure a coffin, Sinclair arranged for the transportation of a casket from Britain to Kenya.

Apart from assisting with the equipment needed to provide a befitting sendoff for Mzee, British military officers also guided their Kenyan counterparts on the procedures for a state funeral, including lying in state.

Cullen adds that the funeral programme for Mzee Kenyatta was largely borrowed from that of former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who was interred on January 30, 1965.

"Given that Kenyan policy-makers had asked to receive programmes from Churchill’s funeral, it appears that those organising the president’s funeral lifted the text almost entirely, editing only slight details," Cullen says.

And so the founding father went to rest in an elaborate ceremony symbolic of his status as the head of state and government.