Tucked away in a corner of her house in Kanyaluo village, Homa Bay county, Peninah Adhiambo gazes pensively at the smartphone before her.

The gadget belongs to her grandson who is waiting for them to be allowed into a virtual court session.

A judge is set to rule on a bail request for Peninah's son who's locked up at a Kisumu prison for stealing and slaughtering a neighbour's donkey.

Peninah would have had to travel to Kisumu for the ruling but the fact that the court would deliver its verdict virtually meant there was no need to take a bus.

Her case is one of the many scenarios brought about by virtual court sessions that are not only saving time and costs but also helping to reduce backlog.

At the start of the current financial year on July 1, 2023, the overall case backlog across the courts stood at 276,678 according to the State of the Judiciary Annual Report for 2022-23.

That represented a decrease of 17 per cent compared to the previous year when the backlog stood at 336,119 cases.

The report attributed the achievement to efforts by judicial officers to expedite hearings and the adoption of technology.

While virtual court proceedings became pronounced in mid-2020 following the coronavirus pandemic, the Judiciary commenced its reforms in automation and digitisation back in 2017.

The piloting targeted electronic filing of case and a case tracking system. These were informed by the need to cure the maladies brought about by the reliance on manual systems which were marred with a lot of inefficiencies.

Today, cases of lost files or litigants travelling long distances and queuing to get services have been collapsed into just logging into the system and filing their cases.

"The introduction of the use of information technology systems in the Judiciary has greatly improved service delivery both in the courtrooms and in the court registries," deputy registrar in charge of automation in the Judiciary Elizabeth Tanui says.

With the e-filing system now effectively rolled out in 13 counties including Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu, the Judiciary is not only looking to improve access to justice but also seeking to clear backlog and have cases concluded within the shortest time possible.

Today, thanks to technology, judicial officers in less busy stations can be assigned to hear and determine virtually, matters from stations with higher caseloads.

For instance, a magistrate in far-flung Lamu, with not many cases, can help hear and determine matters lodged in Nairobi, which is often a busy station.

Tanui says the initiative, dubbed Mahakama Popote (court everywhere), was launched in October 2022. The aim is to leverage on resources and ICT to expedite cases.

"In the 2022-23 financial year, 6,469 cases were referred and 3,313 of them were heard and determined," the annual report states.

The virtual hearings could not have come at a more appropriate time for the Court of Appeal which is struggling to clear a backlog of about 11,000 cases with a shortage of judges.

The court has only three benches in Nairobi and one each in Mombasa, Nakuru, Nyeri and Kisumu. While a fully-fledged court has been inaugurated in Eldoret, it is still served by visiting judges as is the case with sub-registries in Malindi, Kisii, Meru and Kakamega because of shortage.

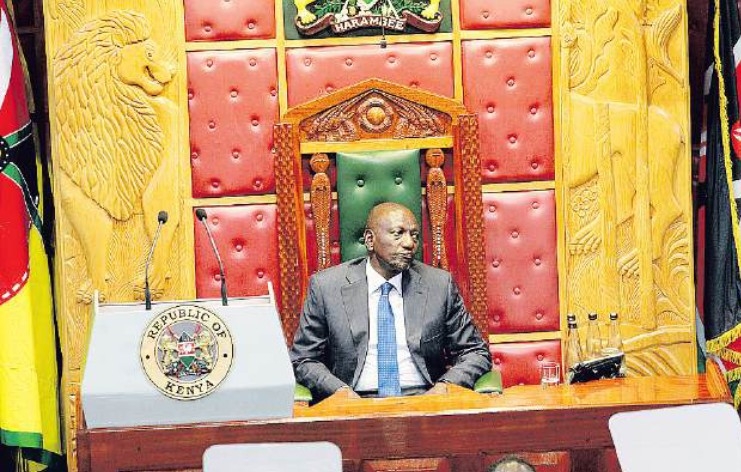

The Court of Appeal is served by 29 judges after President William Ruto appointed four more judges in September 2022. There are ongoing proposals to increase that number to 70 for efficient service delivery.

Court of Appeal president Daniel Musinga, however, says technology has helped the court deal with backlog that would have otherwise increased.

Because of its nature, this court must sit as a bench of at least three judges, says Musinga.

"The challenge comes in situations where a judge has to recuse herself/himself in a matter yet they are only three. It means another judge from another station has to step in for that matter to be heard and determined," Musinga told court reporters during a workshop in Nakuru last month.

"Virtual hearings that enable judges to sit from anywhere will come in handy in such a case. I have personally heard cases even when I'm out of the country," he added.

The annual report shows the Court of Appeal had an increase of 25 per cent in filed cases compared to the last reporting period pointing to the highly litigious nature of Kenyans.

According to Tanui, digitisation has cut on costs, saved time, reduced corruption and improved transparency, brought efficiency in courtrooms and registries and made access to information much easier.

"The e-filing system has especially eradicated the aspect of collusion between judiciary staff and the parties on payment of court fees as revenue leaks are completely sealed off," Tanui told the Star.

Lawyer Moses Audi says virtual sessions have brought massive convenience.

"It has made access to justice easier for litigants especially the old, lactating mothers and people with disability whose physical attendance would have been a challenge," he says.

For lawyers, the benefits are numerous, Moses says. It has enhanced safety by cutting off travel and risks of accidents as lawyers move around to attend courts in various stations across the country.

"It has made it possible for me as a lawyer to attend to cases outside my location of practice. I can attend to a case in Mombasa, Nakuru and Nairobi all in the comfort of my office," Moses says.

Community Initiative Action Group of Kenya executive director Chris Owala has lauded the digitisation process saying its should be supported.

"Enabling people to attend court from wherever they are has greatly saved on costs and time. It has massively improved access to justice," Owala said.

However, virtual court sessions have brought with it a downside that many are still grappling with.

Apart from the problem of internet connectivity especially in remote areas, there are other challenges like power blackout and insufficient infrastructure.

"We are still looking for alternative power for our court stations in case of blackouts. In terms of infrastructure, we have ensured that our magistrates and judges have laptops for virtual hearings. We are now working to see to it that even court assistants are properly aided to help the judges during court proceedings," Tanui says.

Lawyer Danstan Omari, however, feels adoption of technology in the Judiciary has brought with it a disaster.

"Initially, an established lawyer would send the younger colleagues to hold their briefs as they attend to other matters. With virtual sessions, a lawyer is able to attend to all his matters from the comfort of his office. That means a lot of young advocates do not get jobs," Omari says.

"It has also reduced the employment of magistrate and prosecutors because files can be sent to any station. Technology had resulted in 50 per cent of the joblessness currently in the legal fraternity."

He also says the adoption of e-filing systems, which often experience breakdowns, have rendered many cases useless.

Cases filed under certificate of urgency often end up overtaken by events in case the breakdown persists, for say, two days, he says.

With affidavits now served in the e-filing system, clerks who used to work in law firms now have no job.

People like Peninah also believe virtual hearings do not allow family members to meet their relatives in remand unlike physical courts where they would meet and hug in the courtroom.