In a society where FGM and child marriage are deeply entrenched, it takes great courage for men to stand up and openly fight against them.

Their determination and dedication to protect the rights of their daughters, sisters and wives is truly commendable.

Men who have come out to openly denounce the once deeply rooted illegal culture depict and echo the message of progress and equality.

For most Maasai girls, culture deems it necessary for them to undergo FGM, an illegal act that has left thousands of them physically and emotionally scarred.

They are continually robbed of their innocence, voice and future, all in the name of tradition.

In the struggle to find justice for young girls in the Maasai community, women have joined in the race to protect their girls.

The community effort to eradicate the menace now cuts across generations and genders as they seek to be directly involved.

Their scars range from the experiences of their daughters, sisters and siblings who have faced FGM.

Now they are enlightened and empowered to fight FGM to protect girls and nurture their dreams collectively.

LESSONS LEARNT

To Saruni Lenkosho, 48, the trauma of his sister being married off at 13 years is still fresh, like it happened yesterday.

The psychological scars he has sustained from his unsuccessful effort to save his sister is a pain he can’t explain.

To him, the future of his four daughters is more important than the societal recognition one gets after marrying off their young girls.

Lenkosho, a Nyumba Kumi patron in Kimana, explains the repercussions he faces for his stance against FGM and early marriage.

“My four girls have not undergone FGM because I have been enlightened on the dangers of it,” he said.

“My community has been practising that culture for a long time, but I decided to go against it. I encourage my fellow men to end the culture. Some of them listen but others are deeply rooted in it.

“It is hard for them to stop because, in the Maasai culture, mothers are close to their daughters and fathers to their sons. It becomes difficult for the women to convince their husbands otherwise.”

Lenkosho added that there are several advantages in the community that the men are afraid to be denied if they do not follow the culture of the latter.

“There is some small contempt in the society, especially for the men who go against the culture. You get isolated and you will not get information on the happenings in the community,” he said.

He said men who do not take their daughters through FGM are not allowed to eat certain meat in ceremonies. The meat is considered an important part of their culture.

He, however, said that despite all the challenges he faces due to his stance, he will relentlessly continue to fight to protect girls and create awareness against FGM.

For Joseph Lonana, 29, the early marriage of his classmate broke his heart to pieces.

Lonana, a Moran who was born and brought up in Kajiado, went against all odds to study, graduate and become a teacher at Lenkai Christian School.

His passion to save girls from the dreaded knife began when he was just a young boy in Form 2.

Lonana, who was close to his mother, got to learn why girls should be treasured and their dignity preserved.

To him, women were undermined and their right to education was violated due to FGM and early marriage.

He was triggered by a close friend in his class who was married off at a young age.

The girl, he said, was very bright in class, and most classmates looked up to her.

He was pained to see the bright future of the young girl go to waste due to a community that valued their customs more than the dignity of women.

When he finished high school in 2015, Lonana’s passion grew stronger, and he vowed to protect the future of girls in the community.

“After finishing school, I directed all my energy to fighting FGM. At that time, the family, especially my father, isolated me because I decided to help girls around,” he said.

Lonana painfully narrated how he was chased away from their home after he helped his younger sister run away from a planned FGM.

“It was on a Valentine’s Day in February at around 8pm. My father and other community members planned for my sister to undergo FGM. I helped her escape to my grandmother’s place,” he said.

He said word spread around the community and his father found out that he went against his plans.

On coming back home, Lonana found all his belongings packed and he was chased away by his father for two years.

“My father was pained because he had planned everything. Meals were prepared, goats slaughtered and everyone was looking forward to the ceremony, only to find out that my sister was missing,” he said.

To the sister, he is not just a family member but a hero who saved her life and got her educated.

Lonana explained that after everything was calm, he got to reconcile with his father, who allowed him back to the community.

Through his efforts, his sister is currently doing her nursing course, and the father is proud of her.

Lonana has since been in contact with the Hope Beyond Foundation, which rescues girls from FGM and early marriages.

He helps create awareness through speaking in community functions, where fellow moran and men participate.

WOMEN'S VOICE

In the face of patriarchal norms and customs in Kajiado, women have not been left behind in the fight against the vice.

They have courageously faced the risks involved, ranging from criticism to abandoning their matrimonial homes to save their daughters.

The fearless women are determined to put an end to the brutal tradition imposed on girls and women for centuries.

Now empowered, they are raising their voices, breaking the cycle of silence and advocating for the rights of young girls.

Esther Sankau, a mother of six children, is working tirelessly to educate her community, change mindsets and empower other women to stand up against FGM.

As we stepped into her home, we were greeted by a warm and inviting atmosphere. The environment is a sight to behold.

The home has neatly trimmed lawns and a vibrant garden surrounded by different types of fruit trees.

Sankau’s home is filled with the sounds of children playing and birds chirping, creating a welcoming and lively atmosphere.

She attributes the spectacular design of her home to her daughter, who is in college.

Sankau, a farmer and beadmaker in the Noomayianat area in Kajiado, has four daughters and two sons.

She said out of her four daughters, two of them underwent FGM, which was propagated by their late father.

Sankau painfully described the challenges she went through after she refused to let her two other daughters undergo FGM.

“When we went against the culture, we were isolated by our neighbours. It was a must for you to follow what your husband wanted and if not, you were viewed as an abnormal person,” she said.

“It has taken a long time for the community to accept change, but I thank God we have tried and the culture has reduced.”

Sankau said two of her daughters dropped out of school due to FGM, but the other two have successfully been educated and one graduated from university.

“I can now see the difference because my two daughters have gone to school and they will both finish school. Their father had a strong stance and wouldn’t listen to anyone,” she said.

Sankau says women were not allowed to make decisions regarding their daughters.

She has taken up the role of helping other women by speaking during the women's group meetings in a bid to end the illegal culture.

Through the example of her children, she has demonstrated how FGM affects the future of girls in the community, she said.

Women who tried to speak up against the culture of the community suffered immense consequences.

Margaret Naiyeso, a resident of Noomayianat in Kajiado, recounted how she was forced to choose between her marriage and children.

Naiyeso left her matrimonial home and relocated to her parent's place after she refused to circumcise her daughters.

“FGM affects the girls, it leaves a permanent scar that makes it painful to give birth in future,” she said.

“This is why we have stood our ground to fight for their rights. We fight them, and when we hear somebody wants their daughter to undergo FGM, we rush there and try to block them. We have no other way but to do what we can.”

Her three daughters have gone to school. One is married, the second born is in college and the last girl is in high school.

Stories of successful girls in Kajiado have been received with utmost joy from parents and communities.

Parents have indescribable joy narrating the success of the girls despite the harsh community cultural norms that have oppressed them.

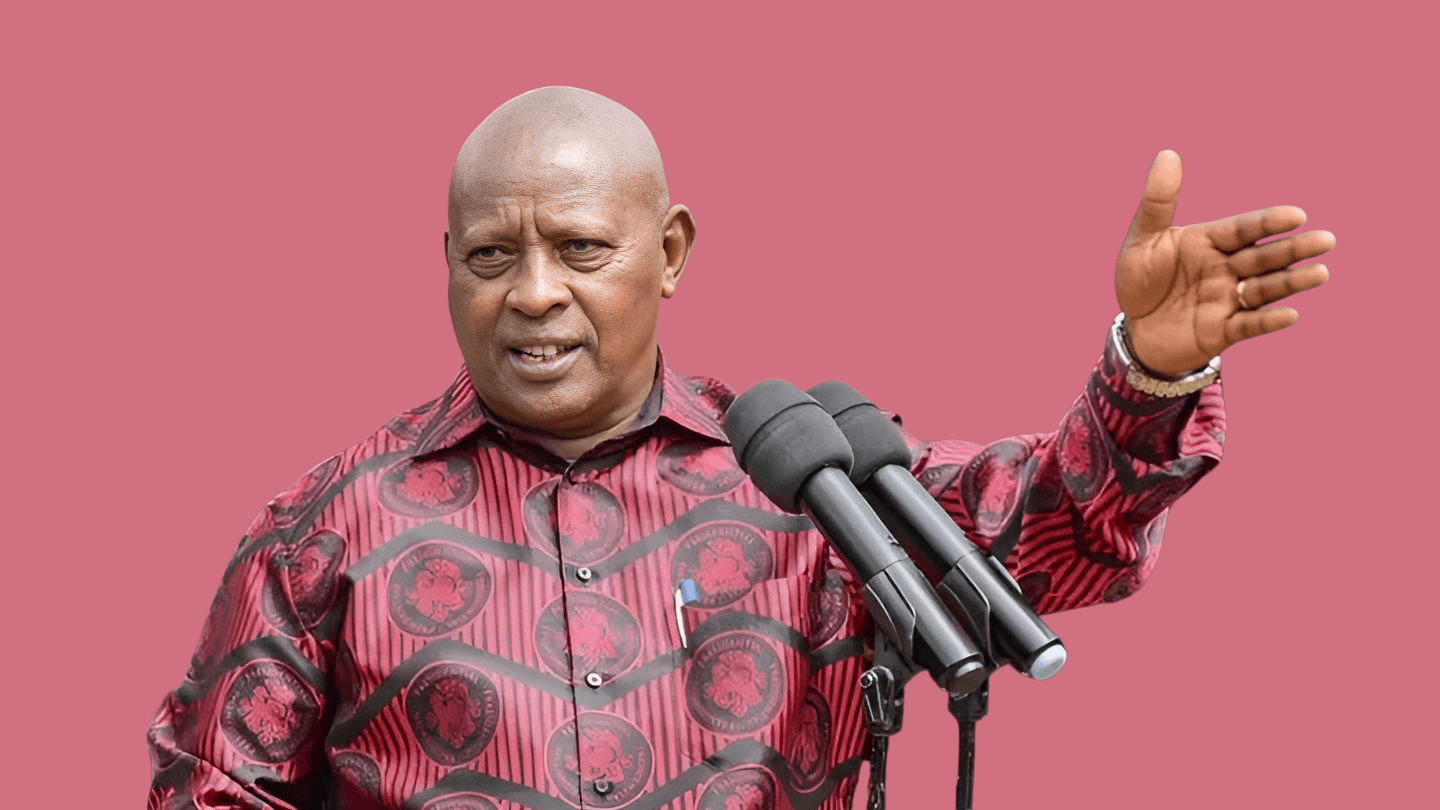

Lekarokia Ole Nang’oro, a proud father of 19 children, has ensured none of his eight daughters was subjected to FGM.

Nang’oro said he observed other tribes that were not subjecting their girls to the illegal culture and decided to emulate them.

“I’m a proud father of eight daughters who have all schooled and one of them is a successful business owner in the United States,” he said.

“It gives me joy to visit her once in a while and affirm my love as a father.”

Like other fathers who stood their ground against FGM, he, too, has not been spared of castigation by fellow community men.

“It is hard to change the minds of old men in the community,” Nang’oro said.

“The only way to end this menace is to teach the young generation of men the dangers of FGM and early marriage. They are young and can easily accept change.”

COMMUNITY JOINS FORCE

Equality Now, an international organisation, has partnered with Hope Beyond Foundation in Kajiado to implement and draft policies on eradicating FGM and economic women empowerment.

Pina Ercolano-Woodward, who works with Equality Now in the End Harmful Practices Project, said the law on FGM was enacted in 2011, cases have reduced but some communities still practise it.

“Most people are away from local advocacy. They have found other interesting ways to circumvent the law,” she said.

“People are now practising cross-border FGM, where some cross to Tanzania to do it.”

She said the organisation has strived to end cross-border FGM by sensitising communities.

Pina said there has been a challenge with data collection because most cases of FGM go unreported.

Dorcus Parit, the founder of Hope Beyond Foundation and Rescue Centre, said they create awareness in communities on the dangers of FGM and child marriage.

She said communities should be engaged with the help of organisations, police, chiefs and Nyumba Kumi to eradicate the menace.

Parit added that the foundation tries to rescue girls before they undergo FGM and provide them with education.

“Men, including fathers and Morans, have come out in large numbers to help in the fight. It has helped us prevent a lot of cases. The rate of FGM was very high in Kajiado,” she said.

Parit said the rate of FGM and child marriage in the county has reduced from 20 per cent to 15 per cent.

Despite the challenges men who fight FGM go through, she said, they have vowed to end the illegal culture.

“We ask the Maasai community and other people who are practising FGM to be at the forefront in fighting for the rights of girls and their future,” Parit said.

WHAT COSTITUTION SAYS

The FGM Act 2011 in Kenya is one of the most comprehensive laws against FGM in Africa. It clearly defines FGM and criminalises the performance, procurement, aiding and abetting of all forms of the practice.

Both medicalised FGM and cross-border FGM are criminalised and punished under the legislation regardless of the age or status of a girl or woman.

According to the Constitution, perpetrators of FGM face imprisonment for a minimum of three years and/or a fine of at least Sh200,000.

If the FGM procedure results in death, Article 19(2) states that the maximum sentence is life imprisonment.

Anyone who performs FGM, including those who are under the supervision of a medical professional or a midwife, commits a criminal offence.

In some countries where FGM has become illegal, the practice has been pushed underground and across borders to avoid prosecution.

Kenya shares borders with other countries where the existence and enforcement of anti-FGM laws varies widely, including Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

The movement of families across borders to perform FGM remains a complex challenge for the campaign to end FGM, leaving women and girls living in border communities vulnerable.