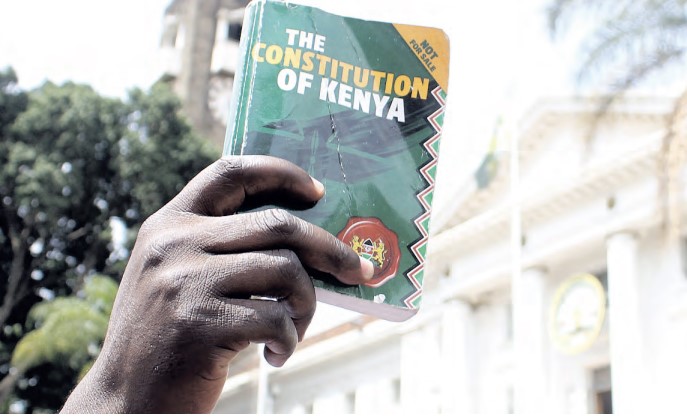

The Kenyan democratic narrative took on a new identity following the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution.

The framers of the constitution led by constitutional expert, Professor Yash Pal Ghai, drove the interests that were presented, represented and protected then.

Those in the situation room now are different; some even vehemently campaigned against the constitution.

How will they infuse old words with their intended new meanings?

Today’s fissured political culture, combined with the ripple effects of the ongoing restructuring of political coalitions and the push by the citizenry to be active public participants in key decision-making, represent another upheaval and create the opportunity to propel social justice.

The three arms of government are responsive to the citizens of the Republic of Kenya.

Those are the clients they serve. In the political arena, truths are claimed and recast by whoever holds the reins of power in the situation room.

In Kenya, the constitution is supposed to be the steadying influence as its words shape and constrain policies and programmes. But the meanings, and even the spirit, of its words, shift with the times, reflecting who has the advantage.

The conundrum we face is how government in its totality can revere the constitution while simultaneously grappling with its contradictions.

Truth be told, this is an internal conflict between constitutional liturgy and political reality.

Are the words enshrined in the Kenyan constitution assuming different meanings over time? Who are the purveyors of this meaning remaking?

The President and his team of executives and civil servants have the duty and responsibility to honour constitutional traditions and a democratic republic while mindful that the meaning of words evolves as the political community transforms.

Contemporary socio-economic problems and cries for social justice accelerate the challenge to broaden our constitutional ecosystem beyond what transpired at the Bomas of Kenya, Kilifi or even Naivasha where our constitution underwent various modes of political midwifery.

Contrasting myth with reality, it is critical to trace how values have been interpreted and reinterpreted since 2010.

What, for instance, swayed the thinking of the judges during the nullification of the 2017 presidential election and the 2022 Building Bridges Initiative, as well as the upholding of the 2024 presidential elections?

In impeaching the deputy president, was Parliament guided by the scripture of the constitution or gyrating to a political tune? Indeed, social change is accompanied by a redefinition of constitutional values; as meanings evolve, privilege shifts.

The Greek word mŷthos refers to the underlying system of interrelated beliefs that characterise a culture. Mythos provides meaning through narratives.

The Kenyan democratic mythos centres around concepts of freedom, transparency, accountability, equality and justice.

Constitutional mythos lulls Kenyans into complacency and conceals contradictions. Moreover, those who draw attention to this imperfect reality are castigated as radicals until altered meanings become the norm.

It is not for nothing that Gen Z activists were christened ‘criminals’.

While Kenyans uphold freedom as a principle, reality demonstrates that a positive vision of freedom — one in which individuals are free to pursue the Kenyan prayer, “Justice be our shield and defender,” and to attain “Plenty within our borders”— is out of reach for most.

While Kenyans pledge allegiance to prosperity and justice for all, the justice system favours the wealthy and imprisons the poor and weak.

The work of state offices is not just complying with the Constitution.

It is about infusing the words and spirit of the constitution and national narrative with meaning.

Commitment to this challenge requires deep reflection if it is to lead to shifts in policy and practice in a way that advances social justice.

As Raila Odinga’s off-and-on association with President William Ruto shows, meaning-making is a moving target that shifts with time, interests and context.

Even when there is reliance on evidence-based decision-making, evidence is always used as part of a narrative, and it is the narrative that alters the constructed images that guide political action Government agencies and state officers through policy-making and development administration are interpreters and implementers of constitutionalism and political reality as are protesters in the streets.

While representative bureaucracy is a given, rarely is it sufficient to ensure that all voices are heard.

Similarly, coproduction efforts, through coalitions, bring more voices to the table, but that, too, is insufficient.

It is the combined effect of three factors — administrative action, representative participants actively engaged in decision-making, and a guiding narrative — that propels social justice and equitable policy implementation.

The writer teaches

Globalisation

and International

Development

at Pwani

University and is

a programmes

associate at DTM, a

media CSO