African leaders came to Baku full of hope that they will strike a trillion-dollar deal on adaptation financing, but as talks drag on and parties dig in, the hope is running out.

In its place, despair and fury have emerged, threatening to scuttle the last days of the talks and send the negotiators back to the drawing board.

At the heart of contention is a framework on a new finance goal, dubbed the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), which many had hoped would unlock the flow of at least $1.3 trillion to the global south from the north.

That money is unlikely to come, as the framework still remains fuzzy and grossly ill-defined.

Negotiators had hoped to have struck a deal on this important goal by Friday last week, but disagreements on four major issues, including setting an adequate target, expanding the contributor base, balancing adaptation and mitigation finance, and developing transparency and accountability mechanisms, had teams burning the midnight oil into the early morning on Sunday.

Still, they had not reached a deal by the time they broke off, and so the talks opened here on Monday with long faces and daggers drawn.

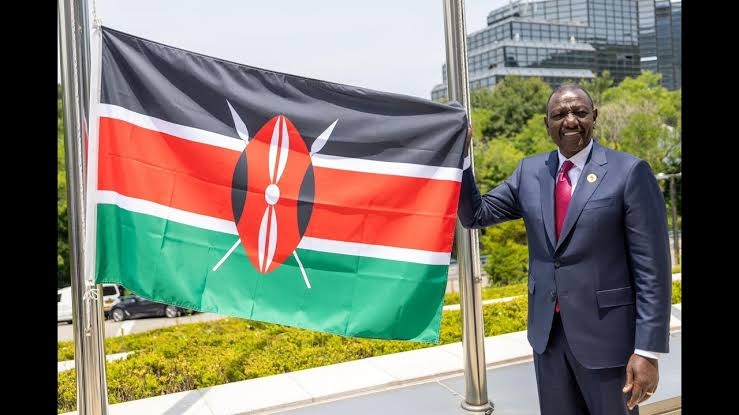

The first to draw blood was

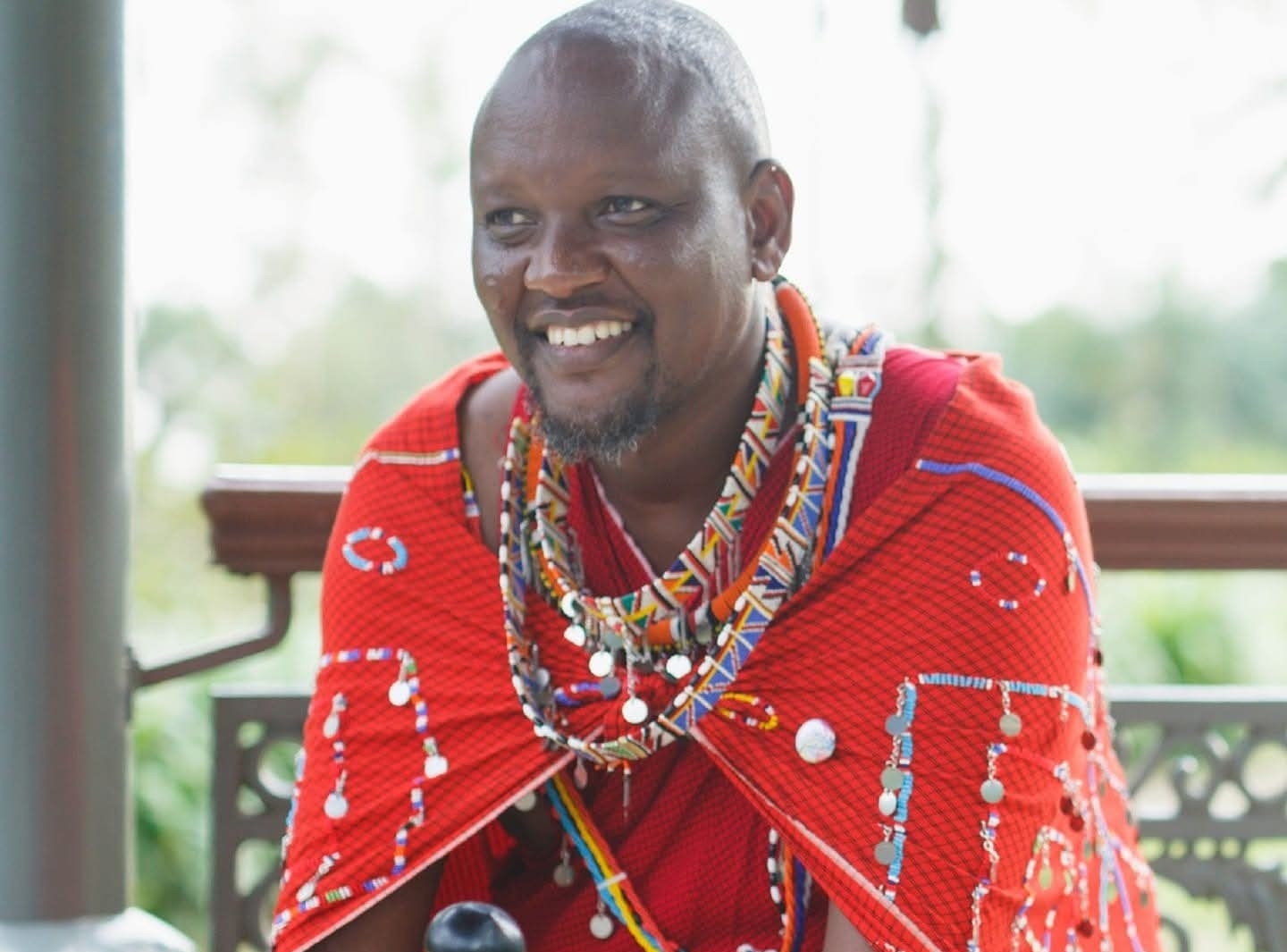

the African Group of Negotiators (AGN), which is led at these talks by Kenya’s

Special Envoy for Climate Change, Mr Ali Mohamed.

In a stinging statement to the plenary, Mohamed warned that “for Africa, the success of the Baku Conference transcends the adoption of agreed texts”, pointing out that success for the continent must manifest as tangible improvements “in the lives of our people, who bear the brunt of climate impacts, and foster a world where transitions deliver shared prosperity”.

“Regrettably,” noted Mohamed, “it appears that COP29 is not yet charting this course.”

A few hours later, the executive secretary of UN Climate Change, Simon Stiell, took to the stage to warn of the dangers of what he called “you first-tism”, or the habit of countries refusing to commit to an agreement unless their perceived adversaries agree to commit to another cause.

“We can’t lose sight of the forest because we are tussling over individual trees, nor can we afford an outbreak of ‘you first-ism’, wherein a group of parties dig in and refuse to move on one issue unless others move elsewhere,” warned Stiell in a short address to the plenary, adding that “this is a recipe for going literally nowhere”.

His words perhaps summed up what has been a painfully slow start to the Baku talks, and pointed to the long nights ahead for negotiators this week as they try to beat a Friday deadline to draw acceptable and agreeable outcomes.

Reacting to the slow pace, Lina Yassin, the adaptation negotiator for Sudan, told The Star that “the lack of ambition and commitment at this COP is deeply disappointing”.

She added:

“The Adaptation Fund falling short by over $200 million, with only $61 million pledged, highlights the persistent gap between rhetoric and action. Despite repeated recognition of the urgent need for adaptation and nature finance, promises remain unfulfilled, leaving vulnerable nations without the resources they desperately need to adapt to and build resilience against climate change.”

She went on to note that, for countries like Sudan and others in the global south, this failure is not just a broken promise; it is a betrayal of those who are already suffering the harshest impacts of the climate crisis.

“The unwillingness to prioritise financing for resilience and adaptation undermines trust and jeopardises the lives and futures of millions,” said Yassin, adding that vulnerable communities who contributed the least to this crisis and continue to suffer from it deserve better.

This afternoon, at a press briefing by a section of the African ministers, speakers protested at what they termed as “unwillingness by the West to engage” and the disdain with which, they said, African positions have been viewed at the COP.

The Gambian minister for environment, Rohey John-Manjang, wondered why rich nations continually refused to understand African perspectives and fund their adaptation plans, yet the continent continues to bear the climatic brunt of the historical pollution of the West.

Sierra Leone’s environment minister Jiwoh Emmanuel Abdulai was even more categorical, noting: “We hope there will be no further delays”.

Over time, the costs to our countries, economies, and ecosystems are rising. The situation is even worse in Tropical Africa.

Forests and biodiversity are particularly suffering from climate change.

The longer we wait, the more expensive it will be in the end. We hope that COP29 will deliver solutions, particularly on the critical issue of climate financing.

But with the tussling getting worse and time running out, hope is fading that Baku will deliver on its finance promise.

So far there have been deals on loss and damage, renewable energy transition and technology transfer, but these have tended to be bilateral in nature and so inadequate to cover the concerns and needs of the south.

Thus, while Africa is presenting a united front, the trickle of money coming in does not seem to target the continent as a collective, but individual countries and organisations.

Cristina Rumbaitis, senior advisor for administration and resilience at the UN Foundation, warned that the talks ran the risk of treating adaptation as an afterthought, and noted that the failure of donors to meet the funding target of the adaptation fund, “the only climate fund dedicated to meeting the adaptation needs of developing countries, is deeply disappointing”.

“We need to ensure that this COP, the finance COP, delivers a new climate goal that delivers the adaptation support that developing countries need. We cannot treat adaptation as an afterthought in this process. Rather, we must treat it as an equal pillar with mitigation as guided by the Paris Agreement,” added Rumbaitis.

And so, as the summit inches towards the finishing line, global attention is now focused on its achievements and shortcomings, as well as its potential legacy.

The coming force of the Loss and Damage Fund, initially established at COP28 in Dubai last year, has been a central focus, with negotiators pushing for mechanisms to make funds accessible to the most vulnerable nations.

However, there are still concerns over whether developed countries will follow through on their financial commitments.

And, as Yusuf Hussein, the Climate Finance Lead at the Office of the Special Envoy for Climate Change in Kenya, said, “calls for innovative funding sources, including levies on fossil fuels and shipping, have gained traction, alongside proposals to increase the capacity of multilateral development banks”.

While the chaos and disagreements of the first 10 days could end up defining the outcomes of the Baku summit, its accidental legacy could be the fact that this is the first COP that emphasised climate justice, with discussions highlighting the disproportionate impacts of climate change on Indigenous communities, women, and climate migrants.

Negotiators have advocated for policies that address these inequities and integrate marginalised voices into decision-making processes, even though, in the end, achieving consensus on legal protections and financial support for these groups has proven challenging.