Members who have sponsored highest number of Bills

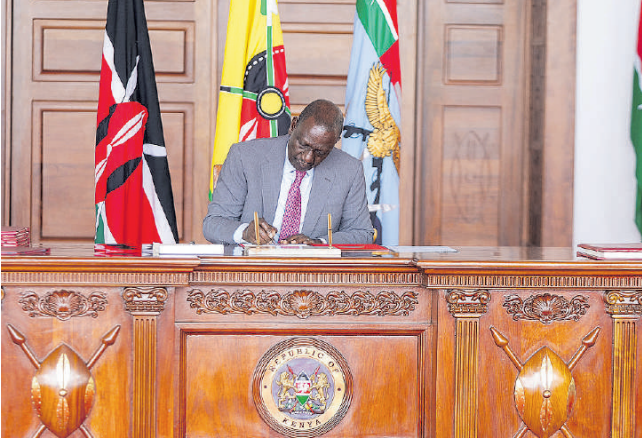

Since the inauguration of the current Parliament after the 2022 elections

Sometimes the Constitution provides consequences.

In Summary

Audio By Vocalize

The Constitution is full of time limits. Most of them say something must be done within a certain number of days or must not last longer than a certain number.

A few examples: A state of emergency must not last longer than 14 days unless the National Assembly extends it. (‡) Election petitions must be filed usually within 28 days after the declaration of the election results – within seven days in Presidential election petitions. (*)

Any by-election must be held within 90 days of a seat becoming vacant. Bills passed by Parliament must be sent to the President within seven days. And Bills assented to by the President must be published in the Gazette within seven days.

The President - not more than 30 days after a general election - must say where and when the first sitting of each House of Parliament will be.

If a motion of no competence in a Cabinet Secretary goes to a select committee of Parliament, it must report to the National Assembly within 10 days.

If a tribunal on the removal of a commissioner sends a recommendation to the President, he must act on it within 30 days. The In

dependent Electoral and Boundaries Commission must act within 90 days if the President requests it to conduct a referendum on an amendment of the constitution At least two months before the end of each financial year, the Division of Revenue Bill and the County Allocation of Revenue Bill must be introduced in Parliament.

Every four months, the Controller of Budget must report to Parliament on the implementation of the national and county government budgets. Parliament had to pass various laws by time limits in Schedule Five of the Constitution.

WHAT IF A TIME LIMIT IS EXCEEDED?

Sometimes the Constitution provides consequences. If the President does not assent to a Bill or refer it back within 14 days, the Bill is taken to have been assented to and become law.

That makes the time limit binding. Sometimes, delays clearly are a disadvantage to people not responsible for the delay.

The ones marked are a few like that. Court cases are the most obvious. So is prolonging a state of emergency, which may limit rights ( marked ‡).

Other time limits are for a good reason - intended to try to make government more effective, yet no consequence of failure is given.

However, the impact of failure to act at all would be very serious, for people who are in no way responsible for the delays. The unmarked limits are such examples.

I believe it makes no sense to say that if the IEBC does not carry out a constitutional referendum within 90 days, it loses the power to do so.

Does the amendment pass without the referendum? Or the amendment dies even if it had unanimous support in Parliament and great support in the public – as shown by opinion polls?

Or if a Bill is not sent to the President within seven days, can it no longer be sent?

Or if Parliament failed to pass law to achieve a constitutional objective in the specified time, even having given themselves a single (permitted) extension, could Parliament never pass such a law? I suspect your gut reaction to each is “Of course not”!

A RECENT CASE

This held that the consequence of not exercising a power within the period required was that it could not be exercised at all. A county assembly had failed to consider a report of the Auditor General on time.

The report concerned the Nairobi City County Alcoholic Drinks Control and Licensing Board and the Auditor General did not publish her report on it for nine months after the end of the financial year (Article 229 (4) gives six months).

Then the Assembly took 10 months to consider the report (Article 229 (8) gives three months). The judge held that the six-month time limit applied even though the Board’s own financial report was submitted more than 20 months late and the audit report came just three months later than that.

He said, “Article 229 (4) is couched in such mandatory terms that leave no room for any other interpretation than the interpretation that the audit and the report can and must be done within a specific timeframe.”

In other words, the constitution tells the Auditor General to do the impossible. The judge relied on several previous cases holding that timelines were binding.

These cases generally involved elections, indeed election petitions. One case was the governor Martin Wambora impeachment case in the Supreme Court.

“All indications … are that expressly prescribed constitutional time frames are binding on the governance processes in place. Even though our specific examples are drawn only from the constitution’s scheme of electoral justice...”

The Court held that the time schedule for the impeachment process of a governor must be adhered to, even if a court order had been issued to stop the process – a decision that raises its own problems.

But even the Supreme Court cannot make binding decisions about matters that are not before the court, so I would argue that this decision applies only to processes for impeachment.

Look at the practical consequences of the recent case. The Auditor General’s processes are extremely important for the nation. She (for the present Auditor General) reveals all sorts of mismanagement and corruption.

If the courts insist that her reports must be “on time” in this strict sense, you are not just penalising the party guilty of delay.

You are letting people identified in the Auditor General’s reports off the hook, giving them an escape route - namely submitting the reports of the body they serve late, making it impossible for this form of accountability to operate.

Similarly, to say Parliament cannot deal with the report beyond three months gives legislators a way to relieve people of the consequences of their failures.

People have already pointed out that Parliament must approve the Auditor General’s annual national audit reports in order that can be used to fix the minimum of allocations to the counties.

If they can’t consider a year’s report because they have not done so in time, the minimum allocation to counties may remain based on older budgetary realities.

A SOLUTION?

There is a concept in law that might be useful. It is of “directory” rather than “mandatory” (compulsory) provisions in law. In 1946, the Governor-General of New Zealand issued the warrant for a general election 26 days after the expiry of the previous Parliament instead of within seven days.

The Court of Appeal held that this was a directory provision and the GG’s failure did not deprive him of the power to issue the warrant.

The idea has been criticised, but if you think of it as a way to work out what the drafters intended, it makes some sense.

The NZCA must have thought: “The lawmakers can’t have meant the GG could no longer issue a warrant and the whole election – and the Parliament elected – were illegal.”

Similarly, if no consequences are specified in the constitution for failure to act on time and their failure means that their power to act is extinguished, with practical consequences that are very serious to the nation not to the people at fault, then the timeline was not intended by the drafters to be mandatory.

It was not the intention that the

courts would craft their own, drastic remedy, not envisaged by the

drafters.

In short, I suggest that - if common sense suggests that the result

of insisting that a timeline is mandatory is: (i) harmful to the public,

(ii) disproportionate to the fault

involved, (iii) seems to frustrate an

important constitutional objective

- then this was not what the constitution drafters intended.

The drafters did not intend ridiculous provisions.

Since the inauguration of the current Parliament after the 2022 elections