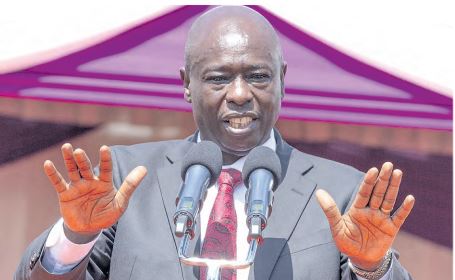

The movement is closely associated with the Mau Mau resistance of yore. Former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua styled himself as a direct descendant of Mau to ingratiate himself with the peasant Kikuyu tribesmen.

The strategy was to cut down Uhuru Kenyatta, who at the time was the leading political figure of the region by being the president. They painted Uhuru as a product of the Komerera, those who lie low and keep quiet. They were the leaders considered sellouts during the Mau insurgence.

They were tolerated but treated with contempt and suspicion. Gachagua did the Kenya Kwanza propaganda so well that the urbane politicians like Prof Kindiki Kithure could not succeed in their quest to be William Ruto’s running mate.

When Gachagua was deposed through impeachment, he turned the narrative into a clarion call. He has since parted ways with the President and emerged as the patron of this movement. The ultimate goal would be to ascend to the throne as the ultimate Gitungati in the mould of Dedan Kimathi.

The rise of this Kikuyu ethnic bile with Ruto and his government stems from the age-old platform of the politics of victimhood. Since independence, the Kikuyu community leaders have used victimhood to mobilise and consolidate their relatively large vote basket into one direction. In 1963, the ravages of the Mau Mau resistance brought them united under Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

This was in spite of the fact the core leadership of the movement deeply distrusted him. When Daniel Moi reduced the influence of his vice president,Mwai Kibaki and Attorney General Charles Njonjo in government, the community organised resistance using various underground movements.

The movements would later coalesce around Kenneth Matiba in the first multiparty elections in 1992. Matiba didn’t win, but Moi got a run for his money.

It was clear the community considered Matiba more of their liberator than Kibaki, with whom they had served in the Moi Cabinet. The duo had resigned to join the resistance movement, but Matiba got the medal when he was detained and later became ill.

Kibaki succeeded Moi because he had suffered under the second regime and consistently championed the people’s agenda. Under the 2010 Constitution, Uhuru and Ruto as his running mate won largely because of the ICC threat.

They had been charged at The Hague for crimes against humanity arising from the postelection violence of 2007-08.

When the Kenyatta’s presidency was dangerously threatened in 1969, the political leaders of the community resorted to oath taking.

There had been a string of unexplained deaths of senior political leaders, which observers considered to be assassinations. Pio Gama Pinto and Tom Mboya fell to assassins’ bullets in broad daylight, while Argwings Kodhek and Dickens Oruko Makasembo died in fatal and suspicious road accidents.

The oaths were therefore designed and administered to ensure that the community rank file remained faithful to their selfish interests and leaders. Since then, the community has had a deep aversion to betrayal and any of their leaders or influential members considered guilty are punished severely.

The Itungati movement is modelled on the framework of the Mau Mau. However, it is modern in organisation and deploys the latest digital technology in communication. For clinical effectiveness, it has deliberately retained the scorched earth ruthlessness of Kimathi’s Mau Mau and later Maina Njenga’s Mungiki.

The movement has totally eclipsed the Hustler movement of the Kenya Kwanza coalition in the Mt Kenya region. In fact, the latter is used as the antithesis of the community.

Any continued association with the Hustler ideology and the government spells doom for the political leaders. After his impeachment, Gachagua has deftly played the victimhood card to his full advantage. He appears in church services, covertly invited and always requested to greet the congregation.

This is against the guidelines issued by the mainstream church leaders in late 2024. Bishops Philip Anyolo of the Catholic Church and his ACK counterpart Jackson ole Sapit had instructed their juniors not to allow the pulpit to be used for political messaging. Indeed, they further ordered the rejection of any donations from political leaders. However, for fear of retribution from the Itungati movement, Gachagua enjoys this privilege unhindered within the Mt Kenya region.

He has proved his critics right. During the impeachment proceedings, he was roundly condemned for not being a national leader. He was accused of pushing and elevating the narrow tribal interests instead of fostering national unity.

Without the encumbrances of state responsibilities, he has heightened his jingoist campaigns. Coincidentally or by design, the media has provided him and team extensive coverage.

The mainstream media has a bone to pick with the current regime on account of business opportunities. They also find it difficult not to push this agenda because of their shareholding and editorial leadership profile.

Therefore, while airtime and space is granted equitably to the government and opposition forces, the content is skewed. The news about Ruto’s regime is more on the complaints and unfulfilled promises than successes registered so far.

The movement is granted prime time and space to dramatise the agony of being betrayed by the hustler that they made president.

By using the expansive virtual space, Gachagua has organised his troops to invade the support bases of political leaders perceived to be against him in the Gema region. He routinely castigates them as Ngaati while extolling the virtues of his supporters as Itungati.

The ground in the Mt Kenya has been hostile to the pro-government political leaders. Ndindi Nyoro of Kiharu and Irungu Kang’ata, the Murang’a governor, have deliberately chosen silence and neutrality.

They prefer not to be openly antagonistic to the government while covertly expressing sympathy with the movement for their survival in 2027.

The Kenya Kwanza political leaders who openly supported the impeachment are regularly denied the podium to address gatherings. And when they are invited to speak in such public events, the crowd becomes hostile either from incitement or base resentment.

Njenga has thrown himself into the mix. Since the heyday of the Mungiki movement, Njenga has remained their revered leader. He was instrumental in Uhuru’s debut presidential bid.

The movement was adversely mentioned in the organised displacement of citizens during the 2007-08 post-election violence. Forceful circumcisions in Naivasha and Nakuru were widely reported. He always found his space back within the government system.

This even at the height of the Mungiki extrajudicial killings to conceal evidence traceability for the Philip Waki Commission and ICC prosecution. His recent reentry into the Mt Kenya kingpin campaign has not gained traction. His critics claim his methods are outdated and rely on brute force supported by crude weapons.

This is considered inconsistent with the current business and social mobilisation models that rely more on technology that is quite dynamic. Gachagua seems to be aware of this, and thus undeterred.

The danger with the incessant campaigns by the Gachagua team is that they are intended to isolate the Kikuyu community for the political poker game. By making his misfortunes in government a community agenda, he has managed to inflame their anger against his erstwhile coalition partners.

For the first time since Kenya became a colony and a modern state for that matter, the Kikuyu community feel that they have been pushed out of government. What irks them most is that the process was successfully executed by the government; they worked overtime to install.

The movement is strategically pushing this propaganda to reinforce the victimhood narrative. Projecting the Kikuyus as the only Kenyans who fought for independence and are therefore entitled is utterly chauvinistic.

The flipside of converting Gachagua’s tribulations with Ruto as Gema betrayal is exclusionist.

The full implications of these activities, overt and covert, are not positive for the stability of the nation. The political leaders in the Mt Kenya region should instead engage in activities and messaging that promote cohesion and national unity.

The government leaders

should also resist any temptation

to engage in policies that would be

interpreted as punishment to the

community.

![[PHOTOS] Ruto shares a glimpse into his farming passion](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F03%2Fc3d9d9f8-3051-457e-93bf-e70e6d01b60a.jpg&w=3840&q=75)