From propping up other organisations to focus on the agitation for queer rights to providing legal and financial support to people pushing for visibility of LGBTQ+ rights, the Kenya Human Rights Commission has been the bulwark for queer acceptance of gays.

A new book details how the lobby has been proactive in partnering with other entities to mount strategic litigation to gradually open up space for LGBTQ+ rights, registering a major win when the Supreme Court decided that lobbies pushing for such rights can be legally recognised.

The book recounts the intrigues behind the lobby’s firm stance in advocating for acceptance and destigmatisation of sexual minorities dating back to the 1990s.

It is titled ‘Rights and Fights: 30 Years of the Kenya Human Rights Commission’s Impactful Legacy’.

The KHRC has over the years faced accusations of propagating homosexuality, a claim that has seen it targeted by state regulatory bodies.

Founding chairman, who served for 30 years upto 2022, Makau Mutua, says in the book that the founding conviction of the NGO was to advocate for all rights, not selecting the ones to focus on and ones to ignore, and that it was also ready to venture into unpopular areas.

“Our gay compatriots – and gay and lesbian rights – are here to stay. Homophobes can take this to the bank – gay and lesbian Kenyans are a political and social fact of life. Their power and influence can only increase. Slowly, more gay Kenyans will come out of the closet and proudly proclaim their sexual identities. This is the arc of history, and it’s unstoppable,” Mutua writes.

“I am not a woman, yet I support women’s rights. I am not a child, yet I support children’s rights. I am not disabled, yet I support the rights of persons with disabilities. I am not a criminal suspect, yet I support the rights of suspects. I am not a prisoner, yet I support the rights of prisoners. I don’t choose which rights to protect, and which to neglect.”

The KHRC took part in strategic litigation on cases that would gradually broaden the understanding of the public and duty bearers on the place of sexual minorities and why their rights should be respected.

The book cites case of RM, an intersex person who sought a court declaration that a third gender existed in Kenya.

The KHRC also published a report in 2011 that detailed the plight of queer Kenyans, their discrimination and what needed to be done for their inclusion.

The lobby hired a programme associate solely focused on LGBTQ work. Erick Gitari, who later formed the National Gays and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, describes how his work at KHRC opened his eyes to the more work that was needed on the rights of sexual minorities.

“I initially sought to register the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission as early as 2012 when I left my job at the KHRC, but the NGOs Coordination Board refused to reserve our name,” Gitari recalls.

Undeterred by the frustration and bureaucratic hurdles that met his efforts, Gitari persevered, making countless trips to the NGOs board to secure registration.

He would meet the board’s legal team who would

dismiss his push as futile, saying he was not the first

person to try to register a gay and lesbian organisation.

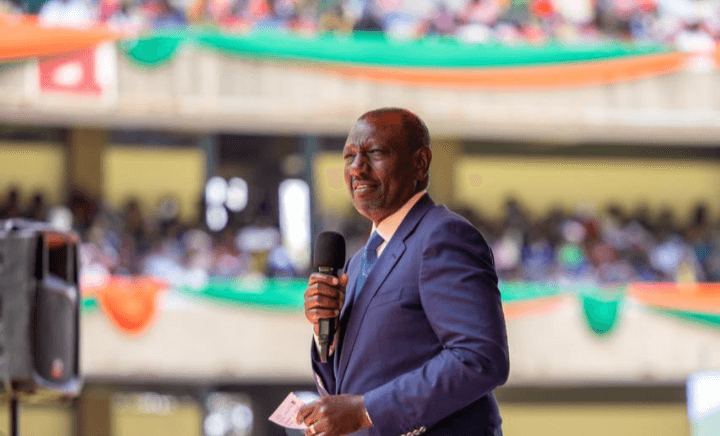

![[PHOTOS] Ruto launches Rironi-Mau Summit road](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F6f6601a6-9bec-4bfc-932e-635b7982daf2.jpg&w=3840&q=100)