Parents of the children

with Down syndrome during a walk in Mombasa.

Parents of the children

with Down syndrome during a walk in Mombasa.They say the limited number of institutions offering such services has left many children without proper care, learning opportunities, or access to crucial therapy sessions.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder that occurs when a child is born with an extra copy of chromosome 21, resulting in developmental and physical challenges.

According to Dr Kathrene Oyieke, a paediatric neurologist at Aga Khan University Hospital in Nairobi, a typical baby is born with 46 chromosomes (23 pairs), but those with down syndrome have 47.

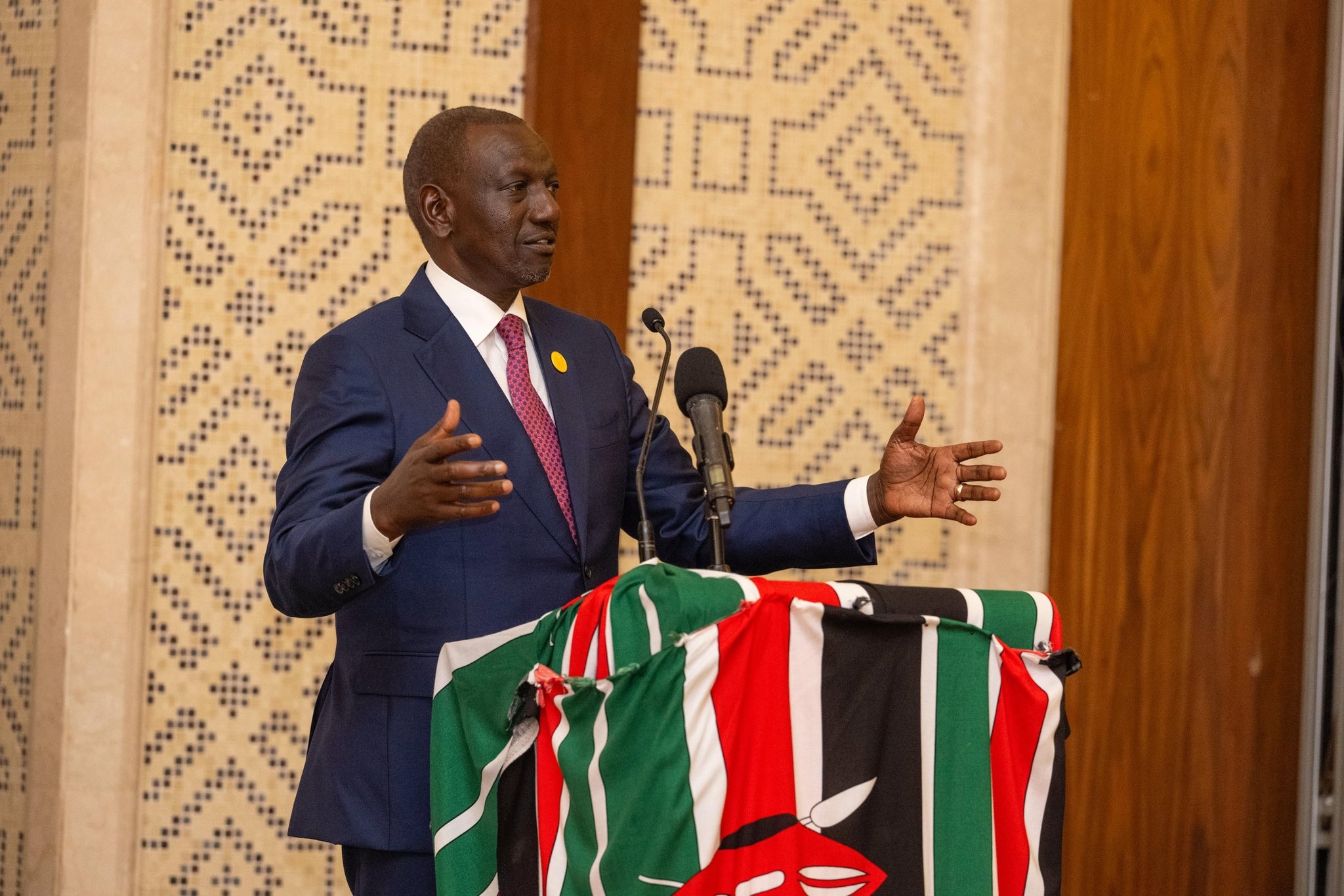

The parents made their appeal during an awareness campaign that began with a procession at Kengeleni in Nyali subcounty and concluded with a colourful event at Kongowea dispensary.

Samuel Wambugu, a parent of a child with Down syndrome, urged fellow parents not to hide their children but to seek help and support.

“This is a lifelong condition. A child can live a normal life, though there may be stunted growth. With proper care, they can develop like other children,” he said.

Wambugu called for the creation of more schools for children with autism and Down syndrome, noting only three such institutions currently serve the entire Coast region.

Wambugu also urged the government to train more teachers in special needs education.

Parent Mgeni Mwachiro shared her experience of fear and confusion when doctors first informed her that her child had Down syndrome, but said counselling helped her accept the situation.

“I want to tell parents not to hide their children. They should come out, meet others and let their children interact. Keeping them indoors only slows their development,” she said.

Mwachiro further appealed to the county government to subsidise the cost of therapy sessions, which she said are often too expensive for many families.

“Most schools that cater to these children are private. The government should build more affordable ones for our families,” she said.

Parent Priscilla Chebocho narrated how her daughter had to undergo heart surgery in India shortly after birth due to complications linked to down syndrome.

“It would be better if local hospitals could perform such surgeries at an affordable rate. Many children die as parents struggle to raise funds for overseas treatment,” she said, adding that therapy should come before formal education.

“Education comes later. First, the child needs to walk, communicate and be self-sufficient. Therapy is crucial, and we would like every dispensary to have an occupational therapist.”

Jonathan Metet, head of disability mainstreaming at the Technical University of Mombasa, urged parents to fight stigma and myths surrounding disabilities.

“Children with disabilities need love, care, and support—not neglect or shame,” he said.

Linda Okusimba, an occupational therapist at Bright Beginning Centre in Nyali, encouraged expectant mothers to attend regular antenatal clinics for early screening and intervention.

Fredrick Muhando, a special needs teacher, reminded the public that children with down syndrome have potential just like any other child.

“They can learn, grow and thrive if given equal opportunities and the right environment,” he said.

Instant analysis

Parents of children living with Down syndrome in the Coast are urging the national and county governments to establish more special schools and therapy centres. They say limited facilities have left many children without access to essential care, education and therapy.