HIS body was found in the dense woodland of a US state park a mile from his home, after a 19-day search by police teams, helicopters, family members, friends and neighbours. And in spite of the sadness of the discovery, some might say it was a fitting end to the extraordinary life of a bohemian maverick whose overriding passion was being in the wild – and particularly, as it happens, in the wilds of Kenya.

Peter Beard, who had dementia and died aged 82 after wandering from his Montauk home on New York’s Long Island, first arrived in Nairobi in 1961, and the spectacular photographs he thereafter took of Kenyan wildlife brought him worldwide acclaim.

Beard befriended Karen Blixen, of Out of Africa fame, in the last year of her life and in 1965 he bought a 45-acre plot next to her former home in Karen. Reportedly, Beard was granted a special dispensation to own land by President Jomo Kenyatta, so that he could promote the people and wildlife of Kenya. (He eventually also had the rights to the film Out of Africa.) Beard named his plot Hog Ranch and this was to be his base for the next four decades.

Hog Ranch was a hodge-podge of tents with thatched roofs – rough and ready, but with the occasional velvet sofa alongside chairs made from bits of dead wood, and bejewelled with an astonishing collection of artefacts and animal remains and everything imaginable that Beard could scavenge. Wild animals wandered through the camp day and night, from leopards and giraffes to the eponymous hogs.

Beard hosted there everyone from royalty to Hollywood royalty, from the world’s immensely rich to local conservationists and models. His film-star good looks and charismatic demeanour ensured he was always surrounded by the most beautiful women and lovers – often several at a time. It was the era of ‘sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll’ and Hog Ranch was no exception.

Beard’s life had begun rather differently. He came from wealthy stock in the US, where his great-grandfather had founded the Great Northern Railway, his grandfather was wealthy tobacco heir Pierre Lorillard, who lived in Tuxedo, New York (and who is credited with inventing the tuxedo) and his father was a Wall Street broker.

Beard grew up in a nine-room apartment on Manhattan’s East Side and studied art at Yale. But he was ‘different’ all his life, eventually rejecting the wealthy and opulent lifestyle he had inherited (though he reportedly had a $1.2 million trust fund).

That is not to say he was not equally at home in New York society as he was at Hog Ranch. He counted among his friends John F Kennedy and his wife Jackie (Beard had an affair with her sister), painters Salvador Dali, Francis Bacon and Andy Warhol, the Rockefellers, writer Truman Capote, numerous film stars, and Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones. His second wife was Cheryl Tiegs, the first American supermodel.

But Beard was happiest in Kenya and he made his photographic reputation with a book about Kenya’s wildlife and the threat to it posed by encroaching civilisation and inadequate conservation methods. The End of The Game: The Last Word from Paradise was published in 1963.

Beard went on to publish many other photographic books, including Eyelids of Morning: The Mingled Destinies of Crocodiles and Men, and Longing for Darkness, the latter the tale of and drawings by Kamante Gatura, Karen Blixen’s erstwhile house steward. Beard sought out Kamante after Blixen’s death in 1962 and eventually took him to live at Hog Ranch, where they set up the unlikely Hog Ranch Art Department.

Beard also ‘discovered’ Iman, the Somali model who is the widow of singer David Bowie. He followed her in the streets of Nairobi until she agreed to let him photograph her, and her career quickly went stratospheric. Iman was the daughter of a diplomat and a doctor living in exile in Tanzania, but Beard, with his taste for colourful hyperbole, promoted her as a goatherd he had found in the wild. Iman, well-educated and multilingual, said she had never come into close contact with a goat in her entire life.

During his career Beard also photographed couture collections for several top designers in the western world of fashion, including at locations such as Lake Turkana.

And one of his pictures of a crocodile was carried aboard Nasa’s Voyager 2 space probe in 1977, as part of what was called the Golden Record, a gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images intended to portray life on earth – just in case any intelligent extra-terrestrials happened to stop by. Beard would have loved that.

Although his photographs were much sought-after, some selling in recent years for tens of thousands of dollars, Beard often lightly dismissed his skill, once describing himself as a “relentless parasite with two panoramic cam[era]s”. Nevertheless, he was one of the first to raise the alarm about poaching and the environment, and his books form a lasting record.

Another record is in the form of his diaries. Jackie Kennedy gave Beard a notebook, insisting that he record his amazing and unusual experiences. It was the beginning of a deeply ingrained habit. For the rest of his life, he assiduously kept a record of his days.

The diaries are not in the conventional narrative style. They are often written in blood – his own and cow blood – and also contain a weird and wonderful collection of the detritus of his everyday life, stuck to the pages.

This could be a sweet wrapper, a dead beetle, a bus ticket, a feather, a receipt, a flat pack of matches, animal droppings, random provocative headlines cut from newspapers, bits of bone and skin, his own doodles, often his hand or footprint made in blood – and all extensively embellished with poetry, from Euripides to TS Eliot’s The Wasteland, which resonated with him strongly.

The diaries were eventually recognised as works of art and, along with his photographs, have been exhibited all over the world, including at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

**

It was February 1992, and in Court Number 1 at the High Court of Kenya the ‘show’ trial of Peter Kipeen and Jonah Magiroi was taking place. The two Maasai game wardens had been wrongly accused (and were eventually acquitted) of killing, dismembering and burning the British tourist Julie Ward, whose remains had been found four years earlier in the Maasai Mara game reserve.

I was covering the trial for The Weekly Review and was sitting as usual with Julie’s mother, Janet, when Peter, attracted by the court drama (as by anything with a hint of spectacle) came in and sat down next to us. He was in his preferred garb – dirty and torn shorts and shirt, a tattered kikoi thrown over his shoulder and rubber sandals made from old tyres.

He was himself none too clean either, but with his skin bronzed deep-brown by the sun, blonde hair, superstar good looks and friendly demeanour, somehow you overlooked it, and Peter became a regular.

One day, he arrived with a guest whom he introduced as an aspiring photographer friend of his. During a break in proceedings, we went to the City Hall cafe for a coffee.

Peter’s guest turned out to be Pamella Bordes, a former Miss India who in the late 1980s had worked in a London brothel that supplied services to a range of well-known names, including clients of the now-disgraced celebrity publicist Max Clifford.

A public scandal had erupted when it was discovered Bordes had a House of Commons parliamentary pass, and was said to be simultaneously ‘dating’ Andrew Neil (then editor of UK’s The Sunday Times), Donald Trelford (then editor of The Observer), UK Conservative minister for sport Colin Moynihan, and billionaire arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi.

Such was life around Peter – always something surprising.

Peter Beard is survived by his Afghan-born third wife, Nejma Khanum, and their adult daughter Zara. Despite a sometimes tempestuous marriage (Nejma once had him committed to a mental institution after he arrived home one day accompanied by two Russian prostitutes) the family was still living together in Montauk at the time of Beard’s disappearance.

Beard often described himself as an escapist, saying that, in Africa, you could escape forever. He was a latter-day adventurer more typical of colonial times but his warning was as modern as can be – the destruction of our wildlife is a harbinger of our own future.

His family’s tribute to him included these words: “Peter was an extraordinary man who led an exceptional life. He lived life to the fullest; he squeezed every drop out of every day.

“He was an intrepid explorer, unfailingly generous, charismatic, and discerning. Peter defined what it means to be open: open to new ideas, new encounters, new people, new ways of living and being.

“He died where he lived: in nature.”

Peter Beard, 22 January, 1938 – 19 April, 2020

Edited by T Jalio

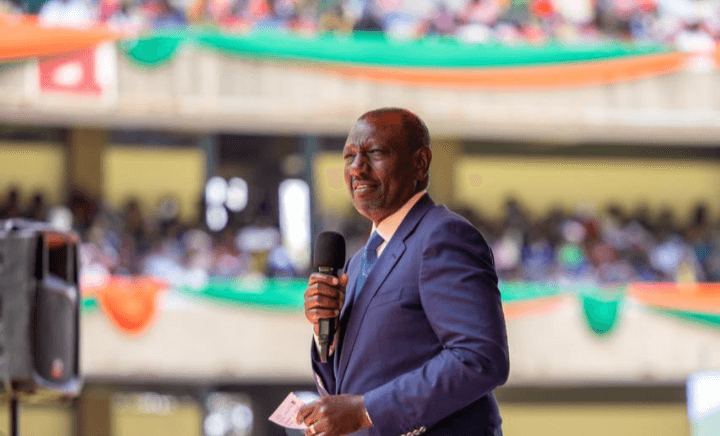

![[PHOTOS] Ruto launches Rironi-Mau Summit road](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F6f6601a6-9bec-4bfc-932e-635b7982daf2.jpg&w=3840&q=100)