When the deadliest tsunami in history swept halfway around the world from Asia to East Africa on Boxing Day in 2004, the government of Kenya issued an alert, instructing people to vacate the beaches immediately.

However, most people were reluctant to leave because they did not know what a tsunami is and the seriousness of the situation.

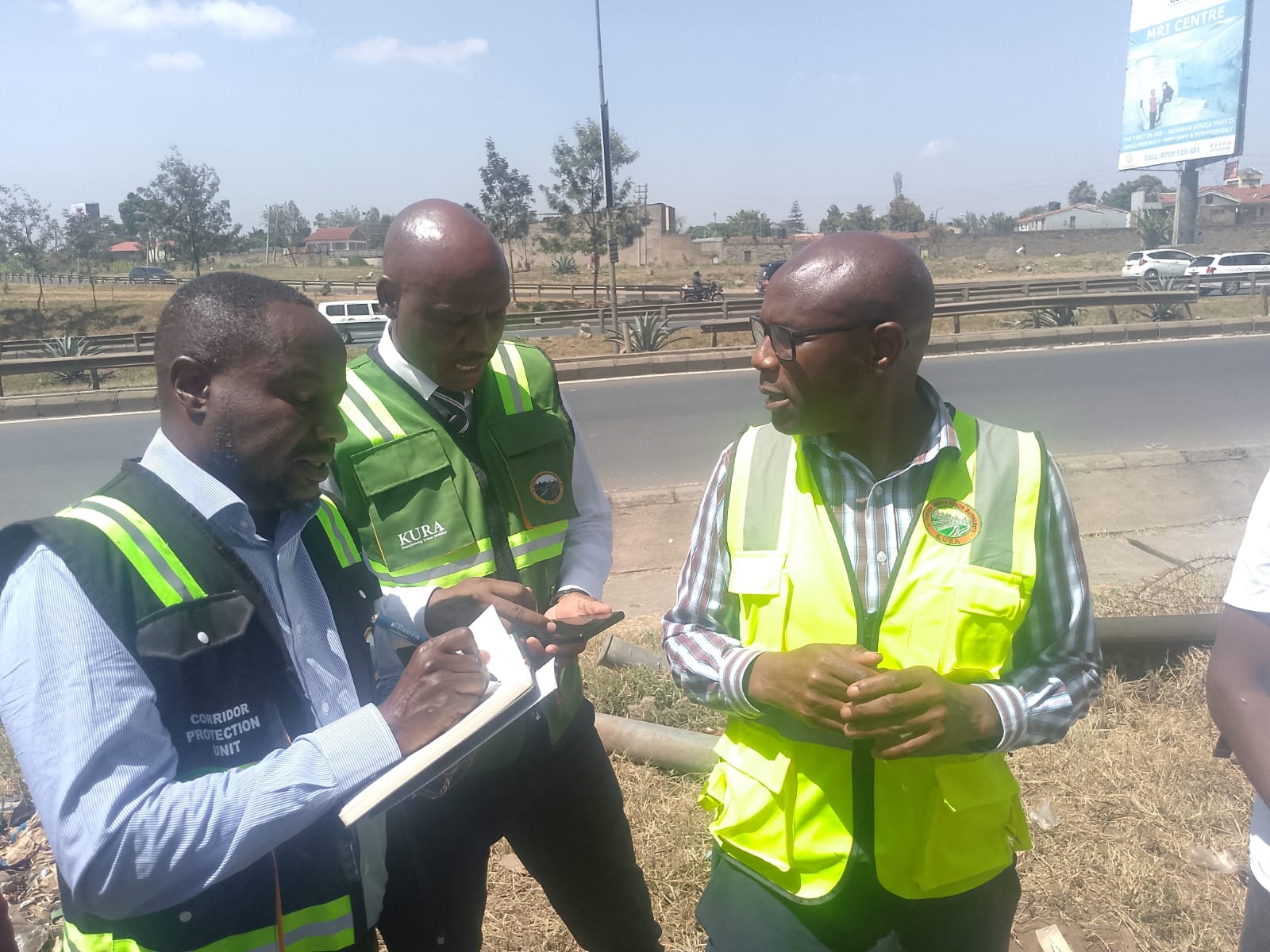

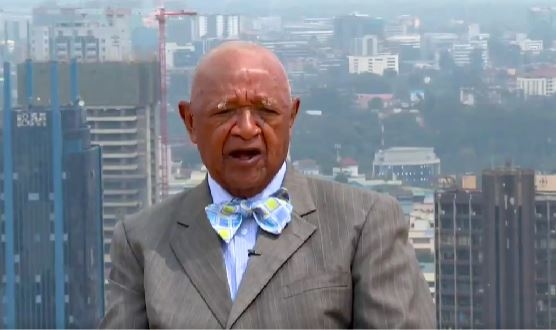

“Out of curiosity, some were even trying to move closer to the beaches to ‘see’ the tsunami,” recalls Charles Magori, a scientist with the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI).

But this was no tourist attraction. It was a disaster in waiting triggered by a 9.0 magnitude earthquake on the seafloor near Aceh, about 100 miles off the coast of Indonesia’s Sumatra Island.

Waves as tall as 30m moving at a speed of 800km/hr were travelling 6,000km to Africa. And though they shrunk and slowed significantly by the time they reached, they still wreaked havoc on the East African coastline from Somalia, where 110 were killed, to Tanzania, which lost 11 lives.

Though only one Kenyan, Samuel Njoroge, was killed, the country’s unpreparedness made it a sitting duck. Rising sea levels and loss of coastal vegetation also make Kenya vulnerable to worse impacts in future.

Countries closer to the epicentre bore the brunt. Overall, the tsunami killed more than 230,000 people, left millions homeless and caused between Sh800 billion and Sh1.5 trillion in damages across India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

Following this tragedy, the international community urged the prompt establishment of a tsunami early warning system in the Indian Ocean, with the intention of extending it to be a multi-hazard system with global coverage.

Kenya had tide gauge stations in Lamu and Mombasa, but there were no official information, warning and response networks. This called for change.

“The 2004 tsunami was a wake-up call for all the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean,” Magori said.

Locally, the fishing industry in Malindi suffered the most due to the destruction of fishing gear and boats and the loss of man-hours.

“Malindi Bay at the Coast was the most affected because it is wide, shallow and open, and there are no coral reefs to shield the bay from the waves propagating from the deep sea,” the scientist said.

The 2004 tsunami was a wake-up call for all the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean

MEASURES TAKEN

A National Tsunami Warning Centre has since been set up at the Kenya Meteorological Department. It works closely with KMFRI and the National Disaster Operation Centre.

In Lamu, the tide gauge station is now a dedicated component of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (IOTWS). Through regional collaboration, the IOTWS was established to assist countries in the region share data and information.

The Lamu station was established in 1996 as part of the Global Sea-Level Observing System network of tide gauges for monitoring sea-level rise as a result of global warming. The Mombasa station was set up a decade earlier, in 1986. Both are maintained and operated by KMFRI.

Magori says data from the stations and others like them in the region can be used to either confirm or cancel a tsunami warning throughout the region.

In addition, the stations can detect and record other extreme oceanic events, such as storm surges and tropical cyclones.

During the 2004 tsunami, the Lamu tide gauge was able to capture and record the tsunami wave that had struck the Kenyan coastline.

Magori says there is a possibility of a tsunami happening in Lamu but says it will all depend on the epicentre and magnitude of an undersea earthquake.

“Tsunamis move silently and most are unnoticed. That was the situation in 2004, when a tsunami came from Sumatra Island in Indonesia. But with the station in place, we won’t be caught off-guard,” Magori said.

“For instance, if the epicentre of the tsunami wave is in Indonesia, the waves will be detected and recorded in countries like India, Sri Lanka, Maldives and Mauritius before they finally hit the Kenyan coastline.”

Through the network, offshore countries will alert the Kenyan station of the wave before it arrives.

It takes about one and a half hours for the wave to arrive in Lamu from Mauritius, which Magori says allows for enough time to alert and evacuate people before the tsunami arrives.

HOW STATION WORKS

Magori says the tide gauge station measures sea level and sends data in real time to the global sea level database at the University of Hawaii's Sea Level Centre in the United States.

The data is used to monitor short- and long-term trends of sea-level variations as part of climate change studies. It is also used by KMFRI to produce tide predictions for Lamu, after which such predictions are distributed to stakeholders and ocean users to facilitate research, navigation and recreation activities.

There are only two tide gauge stations in Kenya: The Mombasa station at the Liwatoni Jetty in Kilindini harbour, and the Lamu station at the Lamu Mangrove Jetty in Lamu island.

Magori explains that tide gauge stations rely mostly on three sensors: the encoder, pressure sensor and radar sensor, which work concurrently to generate and process data.

The encoder consists of a floater and weight, which move vertically, depending on the tidal level and record the water levels.

The pressure sensor is installed below the water to measure the hydrostatic pressure and converts this to water levels, while the radar sensor is installed above the water and sends a radar signal to the water surface. It then receives an echo back and automatically calculates the water level.

“Any slight change in water level is recorded and the sensors are also able to show why,” Magori said.

The station also makes use of satellite antenna for real-time data transmission, solar panels and rechargeable batteries for running the equipment.

The equipment was donated by Unesco-IOC, with financial support from the governments of Finland, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the European Commission.

The KMFRI has deployed two technical staff at the station to manage and ensure a smooth operation.

As a country, we are ready in the event a tsunami hits us. We are investing in the best technology to ensure we record and interpret the smallest of occurrences under the sea

ACHIEVEMENTS

Magori says the station has been crucial in generating data and information that has been used to produce tide tables for Mombasa and Lamu.

The tables have assisted ocean users to plan well for their respective activities.

The scientist explains that analysis of data collected from both the Mombasa and Lamu stations has revealed that the sea level is rising at a rate of about 2mm per year, which is consistent with projections by the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

He says currently, KMFRI, with the support of partners, is building up the two sea-level databases, something he says is crucial in the coastal management and planning as well as mitigation measures.

“What we are saying is, as a country, we are ready in the event a tsunami hits us. And that’s why the government, together with our partners, continues to invest in the best technology to ensure we record and interpret the smallest of occurrences under the sea,” Magori said.

In Kenya, the tsunami hazard is classified as medium which means that there is more than a 10% chance of a potentially-damaging tsunami occurring in the next 50 years.

Research shows that a rise in the sea level can significantly increase the tsunami hazard, which means that smaller tsunamis in future can have the same adverse impacts as big tsunamis would today.

Kenya has only experienced one recorded tsunami, which arose from the Indian Ocean earthquake of 2004, the impact of which was relatively minor.

According to assessments, the Kenyan coast is vulnerable to 2m-high waves and water reaching 500m inland.

Edited by T Jalio