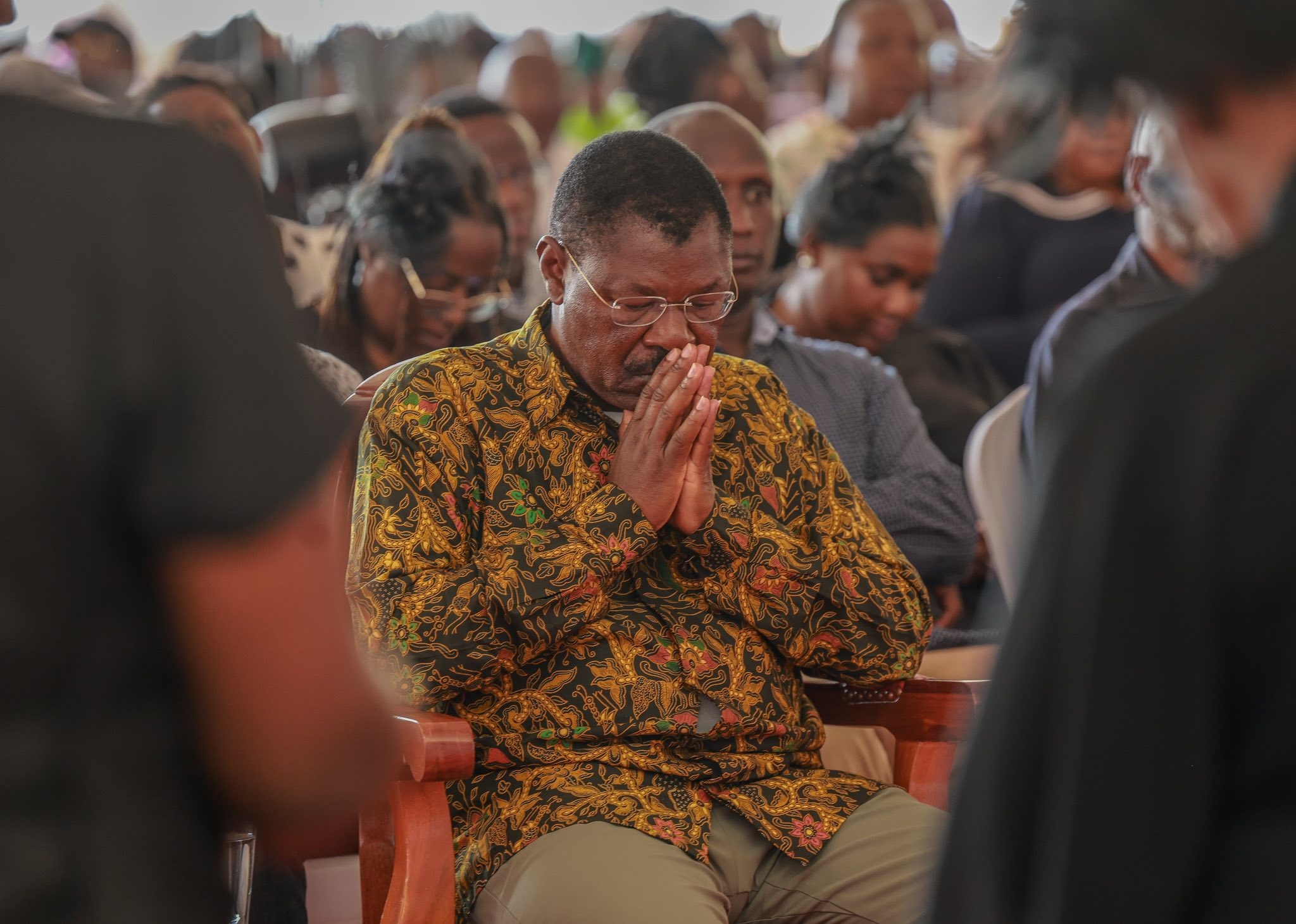

President Uhuru Kenyatta’s eye-catching African shirts have come to symbolise his crusade to revive the textile industry. But the sector manufacturers say could create 5 million jobs is reeling under competition from illicit trade in cheap textiles.

The volume of illicit trade in Kenya stood at Sh826 billion in 2018, according to the Anti-Counterfeit Authority (ACA), which oversees the war on not just counterfeiting but smuggling, piracy, transit fraud or dumping and trade in prohibited or restricted goods.

The authority said 20 per cent of illicit trade is in the textile industry. ACA chairperson Flora Mutahi said counterfeits of premium international brands that are virtually indistinguishable from the original products are sold at cheaper prices.

“It is not in dispute that Eastleigh comes out as a hotspot in Nairobi,” Mutahi said, referring to a shopping centre east of the capital city, popular for clothes and fabrics.

The Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) says another avenue of illicit trade is the use of ‘mitumba’ (second-hand clothes) business to import and export new clothing disguised as second-hand.

In the last six months, the ACA has made many arrests and confiscated Sh3 million worth of textiles and apparel.

“The arrested are mostly of Somali origin. This raises eyebrows on the possibility of the goods transiting through the porous Somali border,” Mutahi said.

But Omar Ahmed, organising secretary of the Eastleigh Business District Association, said you cannot bring goods from China or Turkey through ‘panya’ (illicit) routes and sell them in town.

He said 50 to 100 containers come to the Somali-dominated area every day through ports and planes, all are taxed between Sh2 million and Sh3.5 million each, and the traders have receipts to prove it.

“Those who say we evade taxes are jealous and nervous because we bring more goods. Eighty-five per cent of importers are members of the Somali community,” Omar said.

An incentive for an illicit trader would be to declare new clothes as second-hand clothes, thus allowing for undervaluation. For instance, a Sh600 new shirt is declared as a Sh40 mitumba shirt

MARKET DYNAMICS

Kenya imported Sh131 billion worth of textiles in 2019, Sh18 billion of which were mitumba, according to the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Forty-one per cent of all imports were from China, five times more than from the US, the top exporter of used clothing in the world.

Global Financial Integrity reported that imports from China are particularly prone to potential revenue loss to the Government of Kenya due to under-invoicing.

The Kenya Revenue Authority estimates that the country loses Sh125 billion every year in taxes to traders who falsify the value of goods and services. While it doesn’t include a sector breakdown, the ACA report put textiles as second only to the construction industry in illicit trade.

The import duty on secondhand clothes is 25 per cent or $0.20 (about Sh20) per kg, whichever is higher, while new clothes attract a duty of 30 per cent as from June 2020.

“An incentive for an illicit trader would be to declare new clothes as second-hand clothes, thus allowing for undervaluation. For instance, a Sh600 new shirt is declared as a Sh40 mitumba shirt,” said Abel Kamau, KAM textile and apparel sector executive.

He called for fair enforcement of customs procedures and standards to curb undervaluation, misdeclaration and tax evasion and to level the playing field between locally manufactured products, new imported products and mitumba.

‘BUY KENYA, BUILD KENYA’

Some 1.2 million graduates join the job market each year, but only 400,000 get absorbed in the labour market, according to the Labour ministry.

Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics indicates that 39 per cent of the population is below the age of 15. The unemployment rate, currently at 6.6 per cent, is bound to swell when they come of age.

It is a “recipe for social unrest”, says Ajul Shah, KAM local textile and apparel sector chairman. He asks which industry traditionally employs “hundreds and thousands” of people.

“It’s clothing. Because your shirt or trousers are still very much made by a group of people operating sewing machines,” he said.

“It’s not automated — you put in some fabric in one side of the machine and beautiful trousers come out at the other side; no. It still requires a lot of manpower to stitch.”

In fact, KAM estimates that a fully developed value chain in the textile industry — from cotton farms to textile mills to fashion — could employ 10 per cent of the population, or about 5 million people.

Shah said Kenyans need to be made more conscious of what they are wearing because demand informs supply. And that the government should make concerted efforts to promote local manufacturing.

The President began rallying Kenyans to the cause in 2017 through the ‘Buy Kenya, Build Kenya’ campaign. It encourages citizens and public servants to buy local products, touting their quality and affordability.

Government procurement has led to Sh100 million reinvestment in textile companies enhancing capacity. It is what is keeping the four large manufacturers still in operation afloat in an industry that once had 52.

“Let us encourage each other to proudly wear ‘Made in Kenya’ garments,” the President said when relaunching Rivatex in Eldoret in 2019, leading by example since then as he gets six shirts from the manufacturer every month.

This story was produced by the Star. It was written as part of Wealth of Nations, a media skills development programme run by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. More information at www.wealth-of-nations.org. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.