Founded in the early 1960s, the Luigi Broglio Space Centre served as a spaceport for launching Italian and international satellites from 1967-88.

With the launch of San Marco 2 satellite in 1967, Kenya became the first African country behind the then USSR and the USA to launch a satellite into space.

The centre ceased launching satellites but is still dedicated to receiving satellite data, telemetry and tracking launches.

Safe to say that our beautiful nation has done a number in terms of supporting space exploration. We were really ahead of our time.

In 2018, 1KUNS-PF Cubesat was the first Kenyan-owned satellite to be launched into space.

The Cubesat was developed with financial support obtained when the UoN won a competitive grant from the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) in 2016.

Technical support was provided by Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency.

However, Kenya is going to launch its first-ever operational EO 3U nanosatellite, dubbed Taifa-1, into outer space today.

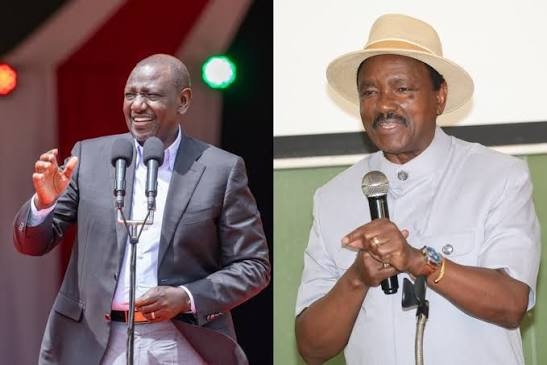

Kenya Space Agency acting director general Brig Hillary Kipkosgei says there are two Kenyan satellites launched into space.

But when it comes to the launch of an actual operational satellite, he said Taifa-1 counts as the first, and it was purely developed by Kenyan engineers.

“In terms of capabilities, the first satellite was basically a technology demonstrator to be used to give our engineers confidence and knowledge to understand what are the basic components of a satellite,” Kipkosgei said.

The Star had an exclusive interview with the KSA DG as well as the team of engineers from Sayari Labs who developed Taifa-1.

DEVELOPING THE NANOSAT

Sayari Labs is a research and development (R&D) arm of KSA used specifically for projects targeting satellite systems development.

Kipkosgei said the institution was founded to help the nation come up with ways to build on national capabilities in satellites and utilisation of satellites for socioeconomic development.

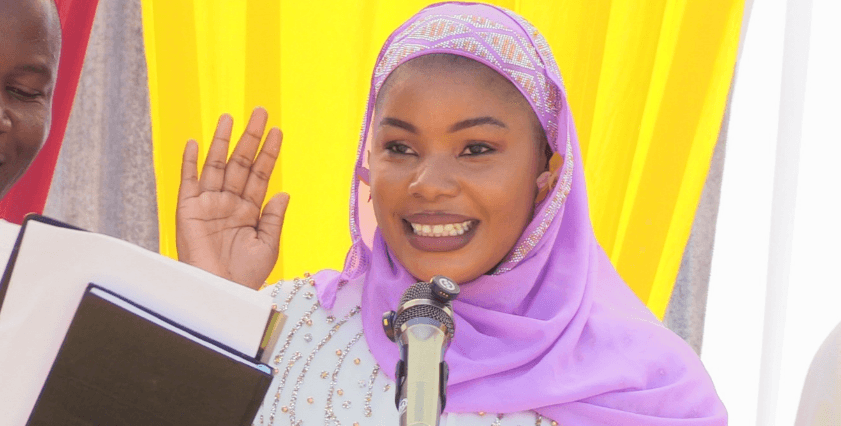

The success of Taifa-1 is greatly attributed to the team of 11 young engineers with a passion for R&D in space matters from Sayari Labs.

They include team and thermal control subsystem lead Rose Njogu, structures and mechanisms subsystem lead Aloyce Were, communication, payload subsystem lead Pattem Odhiambo, electrical power subsystem lead Jackson Koll.

Others are onboard computer subsystem lead Isaac Malin, ground application lead Hope Deche and attitude determination and control subsystem lead Evans Yomu.

There is also embedded firmware engineer Alvyne Mwaniki, structures and mechanisms engineer Maureen Wairimu, embedded hardware engineer Emmanuel Mwanik and business administrator Maureen Amoit.

In satellite sizing, there exist different sizes. These include large, nano and pico satellites.

Taifa-1 is an Earth Observation (EO) 3U nanosatellite.

Rose Njogu says a 1U satellite is a 10x10x10cm satellite, whereby the U stands for Unit.

“A nanosat is any satellite that weighs 1-10kg. Taifa-1 is, therefore, three units put together to form the 3U nanosatellite. A cubesat is a nanosatellite, but not all nanosatellites are cubesats,” she said.

Njogu is an aerospace engineer with nine years of experience working in unmanned systems before moving to space systems.

The mission of Taifa-1 is to take imagery of the Kenyan landscape, and the data recorded will be used for decision support in sectors such as agriculture, food security, general environmental monitory, defence and security.

"As a nation, we are contending with many problems. A number of them can be addressed through data-driven decision support,” Kipkosgei said.

Constituted in 2020, launching Taifa-1 marks the first step in a long series of steps to develop national capabilities in space exploration and exploitation.

“We are using this as a launching pad as we also look into extending our digital broadband footprint,” he said.

‘Taifa’ is a Swahili word that means ‘nation’, and the 1 takes meaning in the bid to become united in facing the challenges that are affecting our country.

Pattem Odhiambo said Taifa-1 marks the beginning of a series of a constellation of satellites that will be helping the country deal with its issues.

Odhiambo is a graduate in electric and electronic engineering from JKUAT, with four years of experience.

Captain Were said there were no specific criteria used to select the team of engineers.

The skillset was brought together based on the needs of the mission.

He is a military officer who graduated as an aeronautical engineer from TUK and acquired a postgrad diploma in satellite communications from Nigeria.

OPERATIONS, TRIAL TESTING

Once Taifa-1 is successfully launched, stabilised and each subsystem gradually powered on, it will basically be orbiting the earth.

Odhiambo said the sat operates by going around the earth in a horizontal position, with the camera placed at the bottom, facing the earth's surface.

The principal operation of the satellite is that when it enters the Kenyan territory, the camera will be taking photos of our landscape.

“It has a power subsystem on board, a computing, communication subsystem that will be supporting its work,” Odhiambo said.

He added that once images are taken, the onboard computing subsystem will instruct the camera to transfer images to radio modules.

The latter will then transfer images from the satellite through a radio link down to the ground station.

“When received, we will begin the image processing chain, where we basically correct the images,” Odhiambo said.

“Just like the way we apply filters on Snapchat or Instagram, our work will be to correct the image that might be affected by speed and atmospheric effects.”

Once rectified, the image is ready to be catalogued and distributed to proper channels for different use and stored for future reference.

In a single day, the satellite is expected to go around the earth 16 times, and out of this, there is a chance that it will be passing over Kenya.

“At night, when we are unable to capture data, we will be dowloading the data from during the day when it passes,” Odhiambo said.

Kipkosgei said Taifa-1 will be issuing imagery at 16m and 32m resolution, which will be used in developing mapping products, land and physical planning aside from solving agricultural issues.

“Imagery acquisition timeline is 5-7 minutes,” he said.

In a week, Taifa-1 will pass over Kenya once or twice, taking images, and four times when downloading the images.

The establishment of a ground receiver station is already at an advanced stage.

Kipksogei said it will be finished by June before it is commissioned around July.

The ground receiver will be located at a governmental site in Kasarani.

Njogu said this facility enables access to the satellite.

“We have a predictive ground track that allows us to tell that at a certain time, Taifa-1 is going to take pictures of a specific area,” Njogu said.

“By using the ground station software, we can task the satellite to take photos. This mission control software allows one to task the satellite even if we are not in the ground station physically. When Taifa-1 goes over Kenya, it will pick the command.”

In this way, Njogu said they can download images already within the camera, any other data, as well as check the health of the satellite.

The team focused much on virtual testing of the satellite having done a number of simulations to ensure the software engineering model worked perfectly.

This was made possible through their development partner, Endurosat.

Odhiambo said after numerous testing exercises, the team is 99 per cent confident Taifa-1 is going to function according to set expectations.

“We have followed the laid-out international standards for quality assurance on the manufacturing front. We are confident it will deliver on every intended objective,” he said.

Njogu said the satellite is expected to come into contact with space debris as well as other satellites, hence they created redundancies in the system.

DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES

The engineers faced a number of challenges in building a satellite from ground zero.

These included the manufacturing of electronics, shortage of electronics due to Covid, service gap, launch service provision, space testing facilities and skills gap.

Odhiambo said it takes a lot for engineers to deliver fully on the skills required to come up with a satellite, when there is little to no manufacturing of some components.

“This is a challenge we surmounted easily given the kind of training we get from our local universities. The shortage, however, really delayed our project,” he said.

Njogu also said the environment where the satellite is supposed to be is still very new to the team.

Nobody is sure what will happen, and it is impossible to bring back the satellite, check it and send it back.

“For it to work, the satellite needs to be worked on in a clean environment, where the electrics are clean,” she said.

“You need the right labs, to handle the components with the right standards and to do exhaustive testing.”

The latter requires a thermal vacuum chamber, which essentially exposes the satellite to all the thermal temperatures it will experience in space while also being in a vacuum.

She said in Africa, such facilities only exist in Egypt and South Africa.

Were said there exists a service gap as there are no insurance companies in Kenya that issue space insurance.

The team had to source for an international insurer, Marsh.

The local market also does not have a company that can provide a launch service.

“In the international market, we identified Exolaunch, which offers spaceflights using SpaceX rockets,” Were said.

CAPACITY SUPPORT

“It cost us Sh50 million to develop, test, launch Taifa-1 and train our engineers, considering the fact that we lack the technical capacity,” Kipkosgei said.

“It was important that we build capacity. There were also laboratory facilities as well as engineering development facilities provision.”

Endurosat, a Bulgarian aerospace company, came on board as a developing partner of Taifa-1.

Were said apart from desktop research and local lecturer consultations, Endurosat took the SayariLabs team through technical training in system engineering.

“They have also supported us through the mission, systems development, satellite registration and identifying potential partners in terms of launch and insurance.”

Endurosat is expected to support in the development of the ground station as well as the first phase of the mission.

“For at least six months, they will be relaying the data on our behalf until we have the ground station up and running,” Were said.

During the build, there were times when the Endurosat team jetted into the country and times when the SayariLabs team used to go to Bulgaria.

However, most of the time, meetings and trainings were done virtually to save on costs.

Locally available private stakeholders like Chalbi Industries also helped the team design space-grade structures and satellite casing.

The government, Were said, has also played a big part in supporting this mission.

“On the registration of the satellite, we worked closely with CA, who did the frequency filing, which was published, and later we were given a licence to operate the satellite,” he said.

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT

Kipkosgei said there is a lot of interest in having an equatorial launch facility, and Kenya, sitting along the equator, offers distinct advantages.

“Nanosatellites across the world are now becoming a thing because nations are looking at miniaturisation of electronics to come up with smaller systems that are capable of doing the job,” he added.

“After we demonstrate the kind of value that will come out of Taifa-1, we hope we will be given the support to come up with more satellites to form a constellation that will give us continuous coverage of what is happening in Kenya.”

“Hopefully, Taifa-2 and 3 will be higher capacity systems.”

Kipkosgei added that the government also plans to establish a commercial space launchpad.

Were said data is the next gold, and the country having acknowledged this proves that we are on the right track.

“Apart from satellites, KSA is spearing for other elaborative programmes, like the operational space weather, which entails studying effects of outer space on earth’s mankind,” he said.

He said equally, Kenya is now leveraging on AI and big data technologies to use data to solve problems.

“We may not be doing big because of limitations and prioritisation of resources, but the little steps we are making are solid,” Were said.

Njogu said KSA is doing a good job in reaching out to educational institutions to bring space learning to consumable levels.

“With the establishment of space clubs in school, children at the grassroots levels can get a chance to see how a planetarium looks like,” she said.

“We are building a young generation that is doing research with the available technology so that by the time they get to where we are, they are revolutionising this space.”