Arrested in 1953 during the state of emergency in Kenya, Mau Mau veteran Maina Macharia was hauled before a kangaroo court at the Criminal Investigation Department and sentenced to death by shooting in Ngong forest.

Instead, he spent five years and four months in 10 different detention camps around the country, flirting with death. Inmates were flogged on the ground to “instil discipline”, some were kept for eight days without food or water as “punishment”, others were stuffed with soil in the mouth until they stopped breathing. But looking back at the age of 95, Maina says he and fellow detainees never lost hope of freedom.

“We didn’t even think of it,” Maina, whose detention number was 7363, says. He embodied the spirit of the liberation movement, officially called the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, which sprung from the Kikuyu in 1946 under the name Forty Group but grew to encompass Embu and Meru communities, as well as units of the Kamba and the Maasai.

Since 1902, Kenyans had been pushed out of the fertile ‘White Highlands’ favoured by Europeans to arid and disease-prone ‘Native Reserves’. And from 1919, they were treated like dogs who had to hang a ‘kipande’ (identification book) around the neck, a humiliation withdrawn after three decades when labour supply exceeded demand, only to be reintroduced in Mt Kenya during the 1952-60 state of emergency, restricting residents from moving without a stamp from an administrator.

FORGOTTEN HISTORY

‘Mau Mau’ was a rallying cry in response to these and other grievances, reflecting a desire for the white man to ‘Get out’ and let Kenyans live freely in the land of ‘Our grandfathers’. The British had their own definition: ‘Civil disobedience’, casting it as a barbaric reaction by savages to civilisation attempts. Which set the stage for a brutal response that persecuted mostly innocent Kenyans, details of which remained covered up for half a century.

Maina’s ordeal is part of that forgotten history. Freedom came at last for him in 1959. He formed the Kiambu Freedom Party in 1960 and joined the campaign to release Kenya’s founding father Jomo Kenyatta and other detainees. His repeated flouting of a directive prohibiting mention of Kenyatta’s name got him banned from addressing public meetings. But he left his mark in politics by preparing, alongside James Gichuru and Dr Munyua Waiyaki, a three-coloured flag for Kenyatta’s party Kanu that later morphed into the National Flag.

From there, Maina turned to education and welfare initiatives, and, with the help of various groups, travelled to India and Pakistan for eight months in 1961. The highlight was meeting Indian Prime Minister Jawahrlal Nehru, whom he requested to liberate the Goa. This activism cost him his passport when he returned to Kenya, but Kenyatta returned it when he became Constitutional Affairs Minister.

After Kenya’s Independence from the British in 1963, Maina focused on trade union affairs, joining the Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotels, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Workers (Kudheiha), which he served for 37 years until 2001. In between, he was invited to Germany in 1989, where he campaigned for the release of Nelson Mandela and dismantling of the Berlin Wall.

LIFE IN RETIREMENT

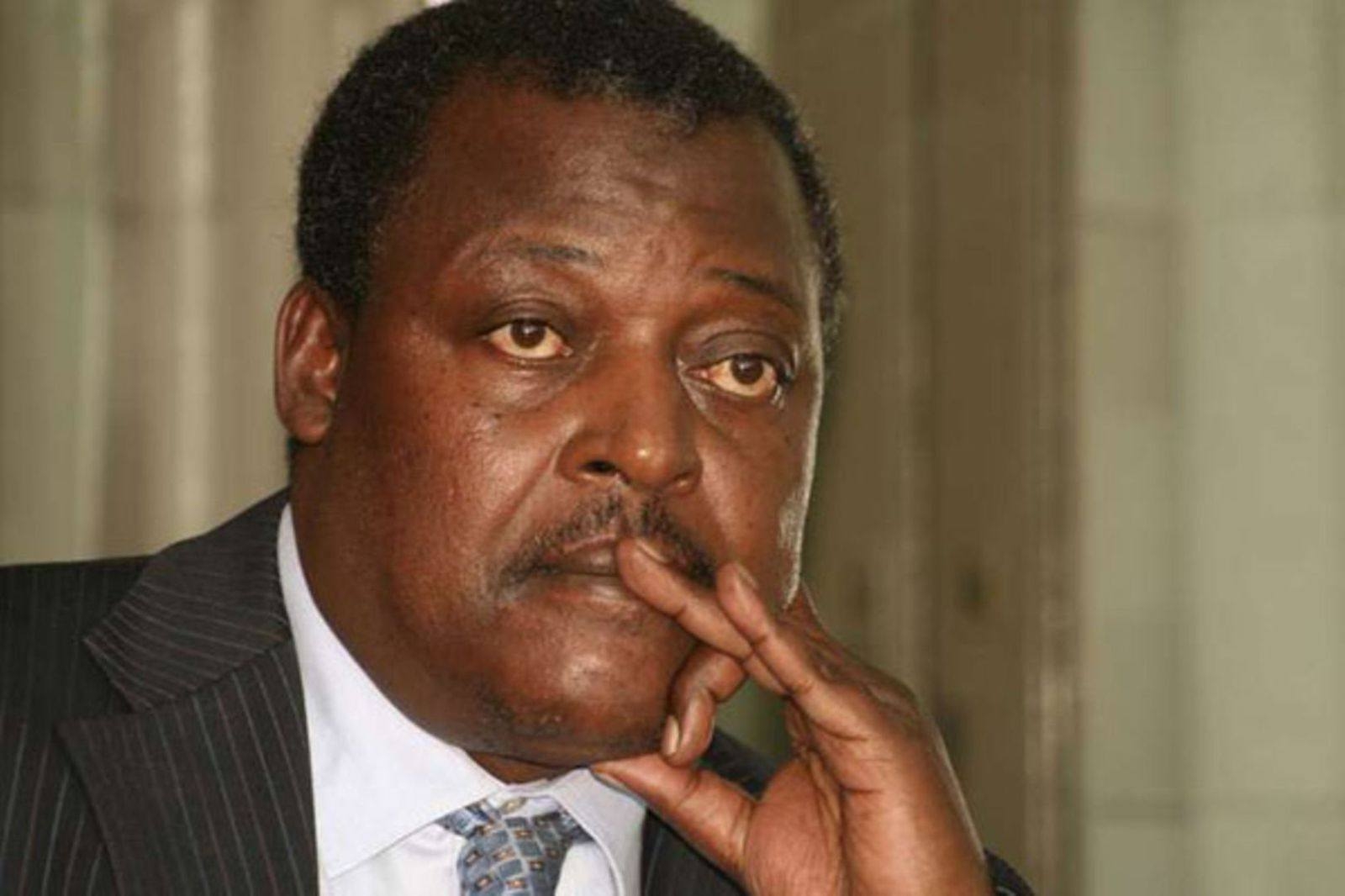

On a warm July afternoon, we find Maina watching the news at his home in Utawala, a 23km drive east of Nairobi CBD, in a single-storey brick building that harkens back to the colonial era. Even at 95, Maina still walks upright. He is lean but healthy. His voice is husky but clear. His memory is sharp, recounting details from as far back as the 1930s, when he was growing up in Kambara village, Murang’a county. His shirt and trousers are official enough, but he pulls on a half coat to dignify the interview.

The mists of time have clouded his countenance, but he only wears glasses at one point, to read our entries in the visitors’ book. He eats solid food without assistance. He hears my soft voice from a metre and a half away, and does not tire as I interview him for two hours. A caretaker helps with housekeeping, but Maina is otherwise independent. “He’s in better shape than I am,” my 76-year-old fixer, Dana, remarked on our way here.

Is the secret his diet? Is it exercise? “It’s God’s will,” says Maina, whose Christian name is Wilson. “Mostly, I don’t drink. I don’t smoke,” he adds.

Maina has outlived his wife, Grace Njeri, and lost one son, but still has five daughters and one other son. One daughter, Laura Njambi, who married into the family of famous British Kenyan author Marjorie Oludhe, was visiting as we arrived. During introductions, we discussed how her father is a mine of information.

Maina longs to write a book some day. He keeps records meticulously, as a tour of his library shows us later. He is a historian who has been camping at the National Archives since the 1970s, unearthing such gems as files from the trial of Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi. In a divide-and-rule system that had many collaborators, Kimathi was sentenced to death by an all-black jury of fellow Kenyans.

Welcoming you to Maina’s home is a framed photo of him and Marjorie alongside Mau Mau Central Committee member Bildad Kaggia. Maina is the last one standing from that photo, which Dana took around 1990. He is one of the last living members of Mau Mau altogether, with most of the rest found in rural areas.

POLITICAL AWAKENING

When you mention ‘Mau Mau’, most people think of dreadlocked warriors raiding the farms of white settlers and African ‘traitors’ at night, hacking them with a panga or shooting them with arrows and homemade guns, destroying their livestock and stealing firearms, before retreating to caves deep in the forest.

Maina took the same oath as the fighters, but he is among the working-class Kenyans who helped the militia from outside. “Even the British thought that only the people in the forest were Mau Mau, they did not know they already had many members in detention,” he says.

His journey to Mau Mau and trade union activism began with his growing up in a world of discrimination. He first went to school in 1935 but dropped out at the end of 1936. In 1940, his father took him to Nairobi to seek employment.

Maina found a city where shops, cinemas, hotels and toilets were classified as: “whites only, Africans and dogs not allowed”. In January 1941, Maina was hired as a kitchen boy in Kilimani, a whites-only residence, where he stayed with his father at the servant’s quarters. By December, he had seen workers being harassed by employers. He also overheard their grievances at a meeting of house boys (they were all called boys regardless of age) working for Europeans. They were restricted to a kanzu (robe) and a khaki short, and not allowed to wear shoes or live with their wives and families.

“I developed a question of: How can I help these people when I get an education?” Maina says. It’s a fire that kept burning in him when he went back to school in 1942, attending a boarding school in Kagumo, Murang’a county, until 1948. He found his voice in January 1947, when he discovered a strength and a way of thinking that he did not know he had before.

He just woke up one day a week before schools opened and decided to form a group with his friends that would stand up to bullies who used to torture newcomers. They named it after the locations they were from in Murang’a: Karigu-ini and Gathuki-ini youth group. From there, they started to fight even against teachers who normally punished them.

TAKING THE OATH

Africans were at the bottom of an academic pyramid that racially segregated schools and curriculums. It put Europeans first, then Goans (Indian-Portuguese), then Indians, Arabs and finally Africans. There were only two high schools for Africans — Alliance and Mang’u — and one college that wasn’t even in Kenya but Uganda, Makerere. “Our education was almost zero,” Maina says.

Trade unionist-turned-politician Tom Mboya would later try to address this by soliciting scholarships in America and Canada for promising African students, which opened doors for such subsequent history makers as Wangari Maathai and Barack Obama Snr.

Maina challenged the ‘colour bar’ in 1947, when he boarded a Kenya Bus to Kilimani and sat in the whites-only first-class section. “All white passengers stood for they could not sit with ‘black monkeys’,” he says. “That’s the name they used to call Africans.” He endured this prejudice without escalation, with the journey proceeding like that. It was nearly a decade before Rosa Parks became famous for similar defiance in America, when she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in Alabama.

All white passengers stood for they could not sit with ‘black monkeys’. That’s the name they used to call Africans

In 1949, while working with the East African High Commission, Maina bought things reserved for whites, such as a tie of the British brand Tootal, and an English newspaper called The Mirror. They refused to sell to him at first, but he argued until they agreed to.

He later formed the Clerks and Commercial Workers’ Union, alongside Bildad Kaggia. Then in 1950, he joined the Transport and Allied Workers’ Union, alongside other Mau Mau icons Fred Kubai and Makhan Singh, and took part in a general strike (coordinated union strikes) when Kubai and Signh were arrested, demanding their release as well as a minimum wage and sick leave.

In 1951, Maina was transferred to Mombasa while working with Weights and Measures, a colonial government department. He joined the Kenya African Union, a nationalist movement that championed land and labour reforms, and that successfully got the ‘kipande’ system abolished.

Discrimination still shadowed Maina, whose trip to Mombasa was marred by a spat with a restaurant manager at Mtito Andei who served his boss but kicked him out, saying food was for whites only.

The final straw came in 1952, when he questioned the use of the Union Jack to decorate Mombasa town while soon-to-be Queen Elizabeth was in the country. Accused of royal insult, Maina was given an ultimatum: apologise or quit. He resigned and joined the Mau Mau.

Maina was elected chairman of the Coast wing of the Mau Mau. He is cagey about the oath-taking, simply terming it a process. But research by Boston University indicates it involved stepping over a line of a goat’s small intestine while pledging to fight to the death for the land and freedom of the country, with the repeated vow that should one betray the cause:

“May this soil and all its products be a curse upon me!”

To be continued.