For 23 years, between 1981 and 2004, Jones Kirati, a member of the minority community Ilchamus, served as a senior chief in Mukutani, Baringo County.

Kirati, however, had to flee from where he had called home due to the constant threats he faced.

“I went to Kajiado with my family due to insecurity, leaving behind a 10-acre piece of land,” he says. He bought two acres in Kajiado but had to sell an acre to get school fees for his children. Kirati says insecurity peaked in 2005.

“The problem is land grabbing instigated by cattle raids. This occasionally displaces the community,” he says.

Since the hostilities began, the Ilchamus community has experienced increasing insecurity and armed attacks from neighbouring ethnic groups.

They inhabit the lowlands of northern Kenya’s Baringo county. Key rituals among the community include those that separate men's age grades, circumcision of boys as initiation into the status of moran, and ceremonies in which morans graduate to the status of junior elders.

The insecurity has curtailed these ceremonies. Kirati says the community is finding it hard to access some sacred sites.

INTENSIFYING ATTACKS

Since the year started, about 17 people are reported to have lost their lives in Saimo Soi ward, Baringo North constituency due to banditry disguised as cattle rustling.

At the same time, more than 11,000 livestock are reported to have been stolen, homes have been destroyed and many residents maimed.

Many have fled their homes and become internally displaced persons. There are more than four IDP camps across the county.

These include Moinonin, Kabaraina, Kimorok, Kaptombes and Chebarsiat.

Due to this insecurity, more than 19 schools in Saimo Soi and Bartabwa wards of Baringo North constituency were closed prematurely before the end of term one this year, when pupils failed to turn up for classes due to migration to safer areas.

Concerned by the recurring confl icts, the community in 2015 allowed the state to convert part of their land to public forest.

The community said poverty was increasing due to loss of traditional livelihood sources arising from the displacement of population from their ancestral homes.

There was also a spike in human-wildlife conflict, natural resource conflict and displacement of the community from their ancestral land.

The community resolved to address the challenges through conservation, management and protection of the hills by gazetting Mukutani Forest as a public forest.

They believed that such a move would guarantee improved water flows for domestic and irrigation purposes from the rivers emanating from the hills and community participation in forest conservation and management.

Other benefits included economic empowerment through ecotourism and other non-consumptive uses of the forest and open up a wildlife migratory corridor connecting Laikipia and Lake Baringo, thus promoting tourism and its associated benefits.

The community believes the conversion of their land into public forest will enhance peace and security in the region and beyond; allow access to the cultural heritage, sacred and religious sites; and opportunities for infrastructure, education, health and general development of other facilities.

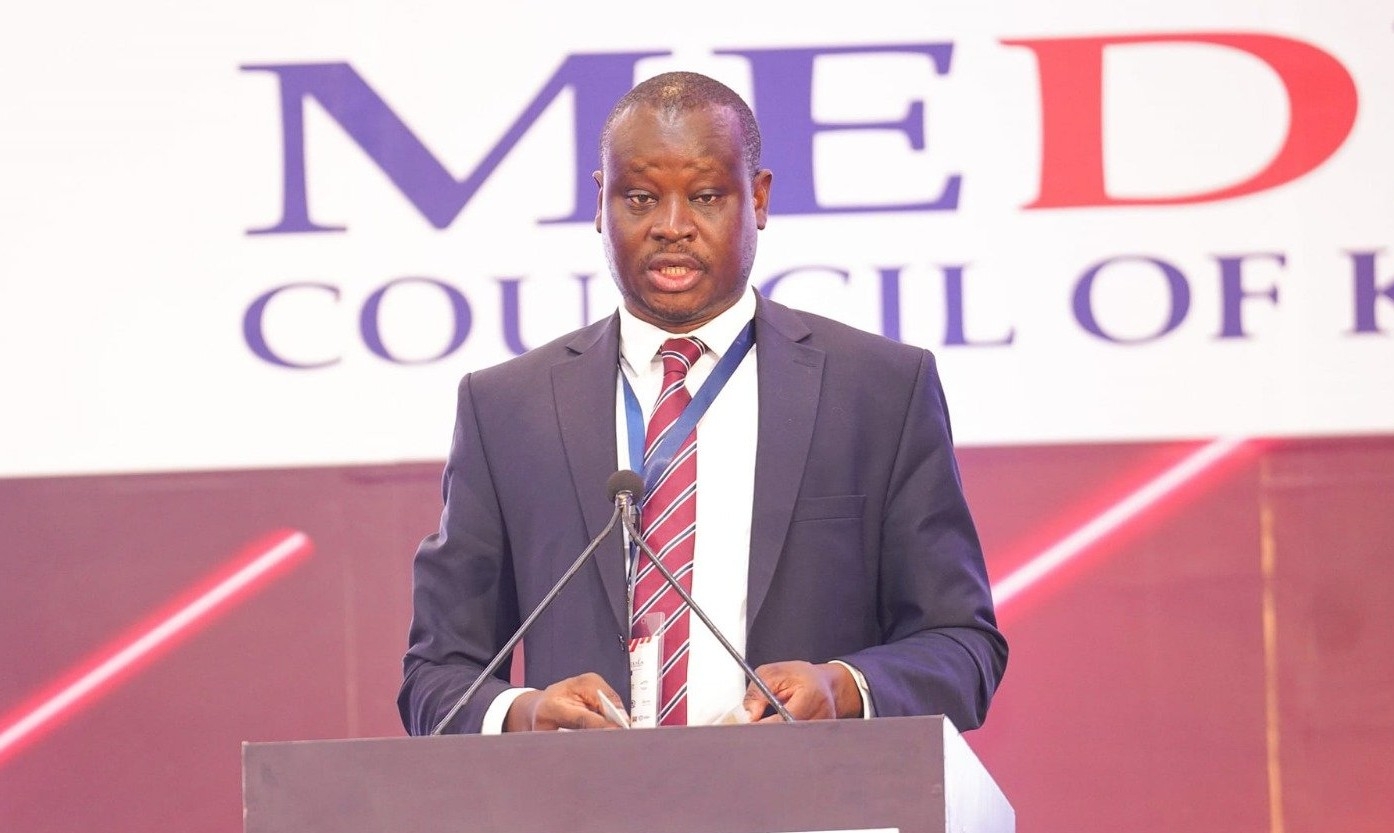

Lemaitai Mukutani Community Forest Association chairman Geoffrey ole Ngusuranga said they had to act after attacks from neighbouring communities intensified.

“We had plans to start a forest but they had not picked up. In 2005, there was a raid by one of the communities, where a number of people were killed,” he says.

“We had started moving out of land when all of a sudden, the displacing community started putting up schools using Constituency Development Fund.”

GAZETTEMENT PROCESS

Ngusuranga says the gazetted Forest is in Mukutani location, Baringo South and none of it is in Tiaty sub-county.

He wonders why certain leaders from Tiaty are meddling with land that is outside their own constituency.

Ngusuranga says the community, which has been marginalised for ages, tried engaging the state about the worrying state of affairs but there was no help.

“We have been marginalised for many years as we did not have representation,” Ngusuranga, a member of the Ilchamus community, says.

The community protested over what they term discrimination in boundaries delimitation, which has cost them elective positions in 2021.

They said their marginalisation was so bad that since the country’s Independence in 1963, not a single member of the community has ever been elected as a Member of Parliament.

The community said their marginalisation was so bad that since the country’s Independence in 1963, not a single member of the community has ever been elected as a Member of Parliament.

Twelve members of the community have filed a class action against the state, seeking an order to compel the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission to demarcate the boundaries of community land belonging to the Ilchamus and register the same as community land.

The Ilchamus, also known as Tiamus, Njamusi or Njemps, are a distinct indigenous Maa-speaking group that settled on the islands of Lake Baringo in the 18th century.

Before the delimitation of counties and wards by IEBC in 2012, they fell within Baringo Central constituency, which had 23 wards, five of which were occupied by the Ilchamus.

The 23 wards were under administration of 54 councillors, only four of whom were lchamus. The remainder of Baringo Central was occupied by Tugen and Pokot communities.

Following delimitation of boundaries, Baringo South constituency was allocated four electoral wards, namely Mukutani, Marigat, Mochongoi and Ilchamus.

The Kenya Population and Housing Census report of 2019 shows that Baringo County has 666,733 people, out of which the Ilchamus comprise a meagre 32,949.

BLOCKS, USER RIGHTS

Mukutani Forest comprises of two blocks, Lemaitai and Mukutani. The Mukutani block lies along the Laikipia Escarpment. It borders Laikipia Ranching to the East and is mainly hilly with gorges and river valleys.

The Lemaitai Block comprises the Lemaitai Hill and borders Lake Baringo to the West. The need for gazettement of two hills was informed by environmental, economic, socio-cultural and security challenges experienced by the community.

A Boundary Plan No. 175/437 was checked and authenticated or approved by the Director of Surveys before the Mukutani Forest block gazetted November 2017 through Legal Notice No. 265 of 27th October, 2017.

Ngusuranga says due process was followed in gazetting the forest and that the Community Forest Association is now reaping the benefits.

KFS has listed CFAs as key elements in forest conservation and management because they are formed by communities that live adjacent to forests.

Sheila Nakure, 28, says security has improved after the land was converted into a forest. Nakure says criminals would waylay her village any time before moving away with large heads of cattle, leaving a trial of destruction.

“We would be escorted by armed security to fetch water and even firewood. Cooking outside in the evening was a tall order as you did not know when the next attack lurked,” Nakure says.

The CFA member says they can now benefit from forest resources. “As a member, I buy fruit trees at a discounted rates of Sh100, while the non-members get a cost of Sh150. The fruit trees have helped improved nutritional value while at the same time increasing tree cover,” Nakure says.

Some user rights that CFAs benefit from include the collection of medicinal herbs, the harvesting of honey, the collection of dead fuel wood, grass harvesting and collecting herbs and honey.

Others are ecotourism, recreational activities and plantation establishments. Nakure says the presence of security forces such as KFS rangers has boosted security. Senior chief Benjamin Lecher said due process was followed during the gazettement of the forest.

“The CFA has since signed a Participatory Forest Management Plan and Forest Management Agreement with KFS, and we expect to get funds that will improve the livelihoods of CFA members,” he says.

Lecher said the presence of KFS rangers in a place that initially acted as a hideout for criminals has tamed illegalities.

The senior chief, who also doubles up as an elder, said attackers from Tiaty have for 10 years denied the community access to important sacred sites in Lemaitai and Mukutani hills, which is a constitutional right.

The eight sites were included in the forest to preserve them rather than having bandits control the area. The sites are now accessible through the invocation of user rights provided by the FCMA 2016.

The KFS is also putting up a training camp in the area, further deterring criminals. But even as the Ilchamus community embraces the gazettement of the Mukutani forest, some political leaders are unhappy with the move.

Early this year, Baringo Women representative Flowrence Jematia requested for information on the declaration of Makutani forest as a public forest. Jematia sought to find out if the process was done in brazen and egregious contravention of the Constitution and Forest Conservation and Management Act, 2016.

She also wanted the decision recalled as contained in the Legal Notice No. 265 dated 27/10/2017.

Jematia also sought to interrogate the process and order that fresh exercise towards the declaration of Mukutani Forest be undertaken by the Environment CS, KFS Board, the National Land Commission and all the relevant stakeholders.

Former Environment CS Soipan Tuya responded to the petition, saying the procedure of gazettement of Mukutani Forest was informed by forest laws where the Ilchamus community gave up their land right for forest conservation purposes for the good of the nation.

“Mukutani forest is a continuation of Laikipia escarpments, which includes Ol Arabel and Marmanet forest blocks,” Tuya said.

“The forest ecosystem largely contributes to the best practices on the management of forest resources for a win-win solution for environmental sustainability and livelihood improvement.”

Tuya said the gazettement of Mukutani forest has contributed more

than 13,000ha to the national tally

of protected forests, and hence the

national long-term plans to increase

the envisaged tree and forest cover.