When he was forced to skip classes back in high school for more than nine months over lack of school fees, Dancan Odhiambo’s future looked bleak.

Never in his wildest dreams would he have imaged that he would rub shoulders with the best architects in the world some day.

But unlike many in his predicament, instead of whining about his sorry situation, Odhiambo took the lemons that life gave him and turned them into lemonade.

Determined to succeed despite the odds, Odhiambo borrowed text books and studied at home, sometimes running ahead of the syllabus.

When he returned to school in Form 2 third term at Kanga High School in Rongo, Migori county, the bright boy emerged top six in his class.

“The principal then wanted me to start from Form 1 all over again. I refused. I argued I had done well in the one-and-a-half terms I had been in the school before I was sent home. “It took a lot of convincing for him to allow me to go to Form 2 in the third term. He had given me many conditions, which fortunately, I fulfilled. He was surprised,” he says.

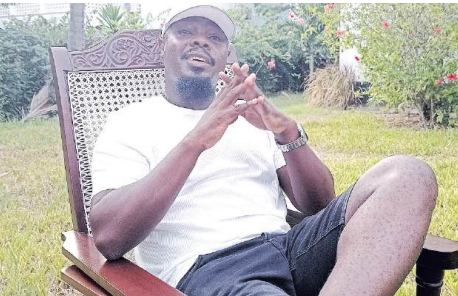

Odhiambo is now an architect who has done more than 450 projects in Kenya, Tanzania, Zanzibar and South Sudan.

He says Kenyan architects are mostly fire-fighting instead of using architecture for socio-economic transformation.

If you had asked him 30 years ago where he would be today, he would not have pictured himself designing and building iconic structures across borders.

Born and bred in Umoja 1 in Eastlands, Nairobi, and the fifth born in a family of seven children, Odhiambo says he enjoyed his childhood, more out of innocence than what was there to be enjoyed.

“I had a very interesting childhood. I can’t really say it was a difficult because I really enjoyed it. Those days in Eastlands, the planning allowed for social interaction. “There were no apartments built illegally. There were many playgrounds. You could see your neighbour anytime not what we experience nowadays,” he says.

He however admits that going through primary school (Unity primary) was the most difficult part of his life. It was not easy for his parents to raise the school fees for all the seven of them.

“My mum was a tailor. That is where I got my very modest architectural skills. My dad is a retired accountant who used to work with Kenya Finespinners,” Odhiambo says.

He was not among the best performers during his formative years because his parents were not that strict, probably because they were seven children and thus ‘there was no time to waste on one child’.

The social space allowed the children in the neighborhood then to play a lot.

However, his elder brother, Fred ,and neighbour Steve Aduda —who is now a doctor—were different from the neighborhood children, arousing his curiosity.

“While everyone else was playing and finding themselves in all kinds of trouble, these two were always studying. In Eastlands those days, there was petty crime and all manner of things. Education almost took a back seat,” Odhiambo says.

He was caught between the two worlds, but then decided to join the two and became some sort of a bookworm.

But when things became tougher for the family, they relocated to Migori county, their countryside home where he joined Bondo Nyironge Primary School.

From there, although his dream was to join Starehe Boys’ Centre, he had to make do with Kanga High School before things became tougher and he had to drop out of school at the beginning of Form 1 second term.

While at home he did menial jobs as he looked to raise money to pay the fees.

He also started buying maize from Migori and selling in Isebania while buying rice in Isebania and selling in Migori.

“I did all manner of jobs including charcoal burning so I could raise fees and study at the same time at night using nyangile (paraffin tin lamp). I was hopeful I would go back to school and finish my studies,” Odhiambo says.

His mother, seeing her son’s determination to succeed, decided to go back to Nairobi to hustle. A trip back to Nairobi, where they now settled in Kayole, saw them introduced to a Catholic priest, Fr Robert Vujs, an architect, who then stepped in and offered to pay the rest of the fees for the rest of Odhiambo’s secondary school.

“The Kanga High principal had insisted we pay the full year’s school fees for both Form 1 and Form 2 before he could re-admit me. I had refused to go back to Form 1. By then my mum had only raised one year’s fees,” Odhiambo says.

Now that his fees was secured, another setback came in. He started becoming sickly throughout Form 3 and Form 4.

“I was coughing all the time, going home when it became too much. My body would swell and I missed class most of the time,” he says.

Due to his good performances, he was placed in a group that the teachers expected to get an A in KCSE. “In Form 2, I was nicknamed Prof because I used to teach other students things taught in Form 3. I got an A plain in my KCSE exams and my name appeared in the papers among the best in the country.”

As a way of giving back to the society and to Fr Vujs, he offered to be washing the Donholm Catholic church in Nairobi every Sunday after mass.

Although he had applied to study medicine at university, he had to follow his passion and pursued a course in architecture at the University of Nairobi.

“Apart from passion, I also had to honour Fr Vujs who had told me I had only two options to pursue. He said I should either become a priest or an architect,” Odhiambo says.

After his first degree, Odhiambo got an opportunity to go to the Cologne School of Design in Germany for an exchange programme for about six months, courtesy of UoN and Goethe Institute.

“This really shaped my architecture. The architecture in Germany opened my eyes. There, I saw some of the greatest architecture by the greatest architects in the world,” Odhiambo says.

Architect Buli Ladu, Odhiambo says, also shaped him by linking him up with the UN where he did his internship.

“I mention these people because they gave me a different perspective of architecture. Architecture is not just designing and building structures. It should provide a way to enhance the socio-economic and environmental growth of the country,” he says.

Odhiambo has employed a lot of interns in his firm, BioSystem Consultants, because he believes in the power of internship.

He says his most iconic project is the Three Villa, a project that he owns. He bought a private parcel, which was derelict in Nyali, Mombasa, where people used to dump garbage.

“The developer, because it was a quarry, could not do anything with it. So, my wife scouted it and told me she had found land that was sloppy and had a lot of breeze. She did not tell me it was a quarry,” Odhiambo says.

“So when I went to see the site, I was shocked. I didn’t understand why my wife wanted me to buy a quarry, which was a big dumping site. But she told me she knew I am an architect and I can do something marvelous with the plot. “That challenged me and I also remembered architecture is about solving problems using designs,” Odhiambo says.

The project, he says, tells a story of

how man and nature should co-exist

and how we travel through time.

The project has been highlighted

in Construction Review, a prestigious

magazine on architecture, which has

published the site twice.