Life has not been a bed of roses for 49-year-old Benard Omolo, alias Kajwang’.

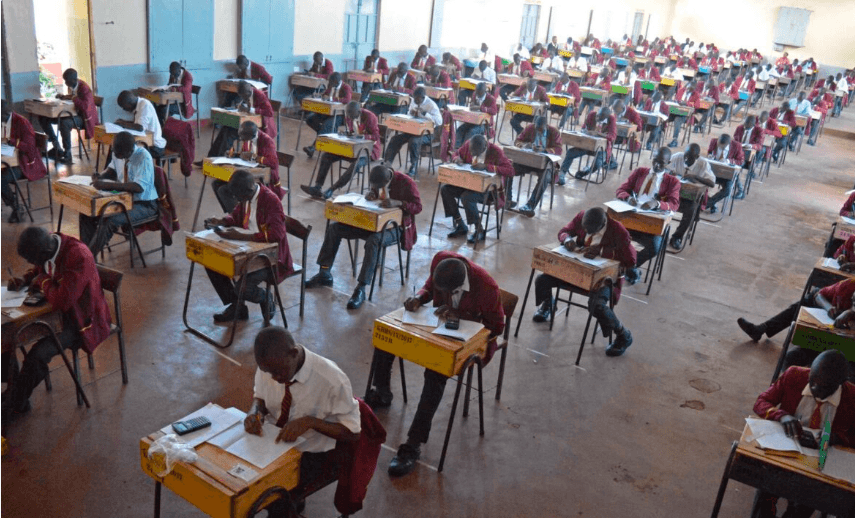

As bright as he is, he never got to fulfil his dream of becoming a doctor. At least, not yet. He had to struggle through primary and secondary school, being in and out because of lack of school fees.

Until he was forced to dropped out in 1989 while in Form 4 at Kokuro Boys High School in Migori county to stay at home in Homa Bay county.

“My father then, seeing I was doing nothing at home, asked me to go to Mombasa where my brother was, to try and find something useful to do,” Omolo says from behind his office desk, a camouflage jacket hanging from his chair.

That same year, he made the journey to Mombasa, where he did odd jobs.

“I have been in jua kali, I have dug trenches and fixed water pipes. I did cabro blocks until I became a specialist. I even did a stint at Kongowea Market,” he says in his husky voice.

At Kongowea, he was a porter, carrying heavy loads for shoppers at a fee, until someone contracted him to sell lemons. He was so good at selling lemons he was poached by a rival trader to sell cabbages. His wages were now higher.

Because he loved education, he did not give up on completing his secondary education. He started going to Mombasa Library and study the same year 1989. He found a way to balance between his odd jobs and studying, which then used to be at Tononoka Hall.

“At around 2pm, I would walk to Tononoka Hall from whatever job I got so I could read books at the library,” he says.

He was good in math and sciences and he quickly made friends, who would head to his seat at the library to be tutored.

In exchange, the friends, who would be in school uniform because they were from different schools, would give him their exercise books to read what they had been taught in class.

“One day [ 1989 ], someone who had been watching me teach other uniformed students at the library approached me and asked me a few questions about my education,” Omolo says.

It turned out the man was working at the Provincial Commissioner’s office and he was curious why students in uniform would always approach him yet he did not go to school.

“After he heard my story, he asked whether I would be willing to register for KCSE exam, even though the registration period had lapsed. It was around May. He made sure I registered at Kilindini High School and eventually I sat my KCSE exam and passed,” he says.

Owing to the experience he had gained at Kongowea, he eventually opened his own vegetable stall. He was elected the market’s secretary general.

“One day in 2015, I went to see the then DO at Kongowea over some matter and saw an advert for the position of chief. I read the requirements and I applied,” he says.

But when he wrote the letter, somehow he did not take it anywhere and stayed with it for almost two weeks, until the deadline day for submission lapsed.

“I stayed with the letter because I suddenly developed doubts about my chances of even being shortlisted. I was not a native, I had come from Homa Bay and was in Mombasa in search of livelihood,” he says.

One day, it had rained so heavily that the roads had been rendered impassable and trucks delivering food to Kongowea from other parts of the country could not access the market.

That meant there was nothing to sell. He stayed at home until he remembered about the application letter. He took the letter to the office of the Kisauni deputy county commissioner, where he went straight to the human resource officer “God gave me wisdom. The HR asked me what the letter was for and I told her I did not know and lied that I had been sent by the deputy county commissioner, I knew she could not call to confirm,” he says.

By this time, people had already been shortlisted for interviews and his name had to be “fixed” on the shortlist and two days later, he received a text message to go for interview.

“The day of the interview was on a Thursday and I was 12th on the list. But looking at the faces of those who entered before me, I got confident I would do better than most of them because their facial expressions showed they were unhappy with themselves,” he says.

He scored the highest marks with 89 per cent. His closest challenger had 69 per cent and the third highest performer, a native, had 59 per cent.

However, the results were withheld because political intrigues crept in.

“There were noises that I was not a native and did not deserve the chance and there was talk people would block my taking office at Maweni location,” Omolo says.

“However, I thank former county commissioner Nelson Marwa because he stood firm and I was escorted by police to the office in the company of Marwa himself.”

When he took office as Maweni chief, the crime rate was high.

He worked in collaboration with the police and arrests were made.

“But one day I sat in my office and asked myself a lot of questions. What is the benefit of these boys [suspects] going to prison? I thought of ways to make them quit crime and do something meaningful with their lives,” he says.

He started talking to them.

“At first they were rigid. How can a chief come talk to them? To them, I was like the police. But through persistence, they started accepting me because I would talk to them like a father,” Omolo says.

Word started spreading among the juvenile criminal gang community that chief Omolo is not like the others and is not bad.

However, some people started mudslinging him saying he was colluding with the juvenile criminal gang members.

“They even said the boys would steal things like phones and bring them to me to sell. However, my superiors who had started investigating me, eventually realised that crime rate in my area and the larger Nyali had gone down and the allegations against me were not true,” Omolo says.

His style eventually earned praise and he would be invited to other areas to talk to young people.

He has even been invited to Nakuru county to talk to wayward youth.

“We were having regular barazas. I used to take with me those who had reformed to the barazas and used them as examples that it is possible to reform and lead a normal successful life without fear of being killed by a mob or the police,” he says.

Many former juvenile criminal gang members who reformed are doing well. “Some got married, some have decent jobs and other have started businesses. That is my happiness,” he says.