Former Attorney General, the late Charles Njonjo, was not given justice when a Commission of Inquiry probed his alleged subversive activities during ex- President Daniel Moi’s regime.

In his autobiography, former appeals judge Onyango Otieno said the commission was the “worst” case he had ever handled in his decades-long law career.

“I do not hesitate to say that in all cases I appeared, this was the worst conducted case,” Otieno, who was a member of the commission, said in the book titled ‘From Village to Village’.

The commission was chaired by Guyanese-Kenyan Chief Justice Cecil Miller, with Justices CB Medan and Effie Owuor as members.

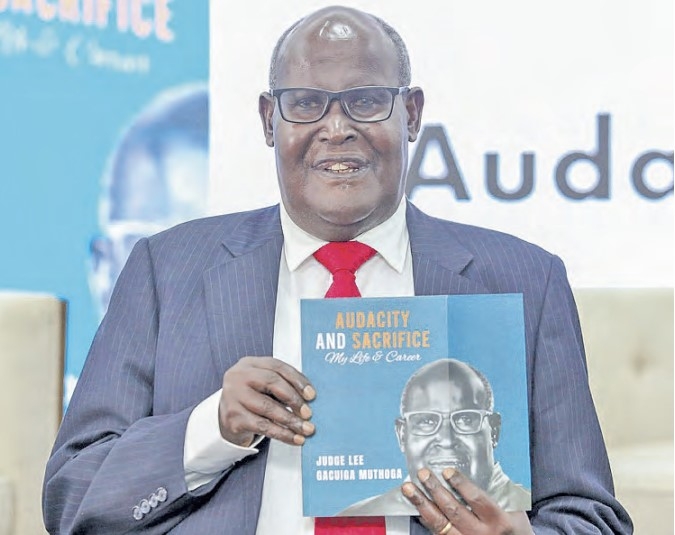

Moi formed the Commission against Njonjo and Otieno alongside Lee Muthoga and Timon Njugi were appointed prosecutors.

Lawyers AR Kapila and SM Otieno were appointed as consultants.

“My own observation as one of the assistants to the commission is that quite a bit of it was no more than politics,” Otieno writes.

Njonjo served as the MP for Kikuyu and as Minister for Constitutional Affairs. He midwifed the late Moi’s smooth ascendancy to Presidency in 1978, after the death of Jomo Kenyatta.

But less than four years down the line, accusations of plotting to grab power from Moi began to spread.

Njonjo was accused of amassing weapons and coordinating efforts in the build up to the 1982 attempted coup.

It was claimed that he used his power and clout as a Moi minister to develop international networks, before leveraging it to import a large cache of weapons and ammunition into the country.

Njonjo was also accused of installing “ground-to-air and air-toground transmitting and receiving radio equipment…” in a property along Lenana Road belonging to a family known as Haryantos.

But Otieno says all that was hot air.

From racist undertones against Njonjo’s lead lawyer William Deverell - who was white - to presiding judges being biased, the dice seemed to have been cast against the former AG even before the commission had its maiden sitting.

Njonjo hired Deverell, who later became a judge, alongside Paul Muite.

Miller frustrated efforts by Njonjo’s lawyers to mount a defence, as he would be openly biased and block them from cross examining witnesses.

“We did everything in search of hard facts. However, I must admit that not much came out which would have warranted “crucifying” Njonjo,” the book reads.

“In my humble opinion, on the criminal aspects, I could not see any tangible or proper evidence that would at least meet the required threshold to find Njonjo guilty.”

It was largely a political theatre, Otieno writes, disclosing that the commission was meant to be independent, but that was an illusion.

“... there were many issues on which we had to consult the then Attorney General Guy Muli [but] unfortunately, whenever we felt that certain aspects could not warrant prosecution and we wanted to bring the same to the attention of the President [as the appointing authority], we found that the Attorney General literally feared approaching the President. Our last resort was Simeon Nyachae, the then chief secretary, who was very useful.”

Otieno says while it was upon him, Muthoga and Njugi to push the cases against Njonjo, he was “not at ease with the way Miller conducted the proceedings”.

“He was also biased against Deverell. I still remember times he would point at the back of his finger indicating clearly that Deverell was a white,” the book reads.

But why did Otieno stay on, if he fundamentally disagreed with the conduct of the commission’s proceedings?

The judge explains that he did not want to be on the cross hairs, citing the political repression that was rife at the time.

“One may ask why I did not resign? The reason is that at this time of Moi’s Presidency, the authorities, particularly the President, was in practice not limited in his power as even powers of detention without trial existed. Further, Kenya was still a one-party state, meaning that such a risk would leave one with none to defend you.”

Njonjo was finally found guilty, but Otieno said justice was not served.

“...as a person who was a victim of some of [Njonjo] his actions as the Attorney General and also having seen and heard him in action, do not think justice was done to him.”

The victimisation Otieno references is that he was denied promotion to magistracy in the early 70s.

In 1972, James Wicks - the Chief Justice at the time - was to elevate Otieno to senior resident magistrate in Kisii.

But Otieno alleges Njonjo blocked that proposal before the Judicial Service Commission.

The decision saw him quit judicial service in a huff and ventured into private practice. He only returned to the bench in 1998, when he was appointed High court judge.

Otieno started his law career as a deputy registrar of the High Court and at the same time served as a resident magistrate.

He was elected to the appeals bench in 2003.

The judge, now retired and aged 83, lives a quiet life in his rural home in Asembo, Siaya county.