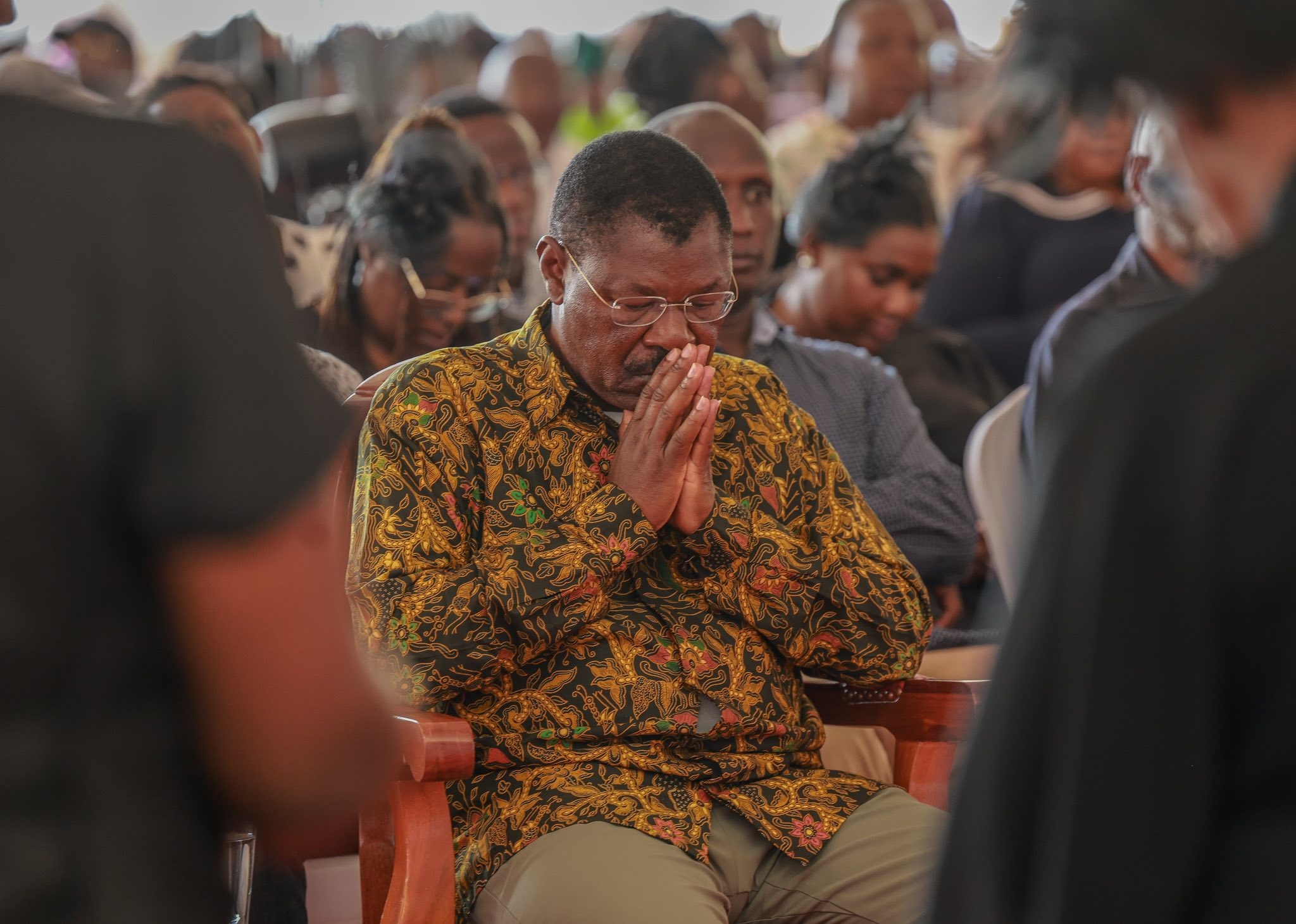

On Thursday, June 25, John Waluke, the Sirisia MP and Grace Wakhungu were sentenced for fraudulently acquiring Sh297 million from the National Cereals and Produce Board. In what may be a truly groundbreaking case, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions was able to prove to the court that the pair had illegally obtained the money from the state agency in a scam related to the procurement of 40,000 tonnes of maize.

One of the key elements of this investigation was getting evidence from South Africa that nullified the defendants’ claims of making payments for storage of the maize. A company called Chelsea Freight in South Africa was alleged to have been paid substantial sums for storing the maize by Erad Supplies & General Contractors Limited, of which Waluke and Wakhungu were co-directors.

The invoices were false, but to prove that required evidence from South Africa. Waluke and Wakhungu had assumed this would be unattainable. Unluckily for them, through international cooperation with South Africa under the provisions of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission was able to get hold of the evidence. In addition, the EACC managed to arrange for the witnesses to come to Nairobi and testify.

The process for getting international assistance is not straightforward. However, Kenya and the EACC in particular have taken great strides in this area. Kenya was the only Commonwealth country in Africa to score 100 per cent in mutual legal assistance in corruption matters in a United Nations assessment in 2018.

As we move forward into a digital society, there is a growing need for international cooperation on criminal matters to evolve. It remains a highly resource-intensive exercise and requires particular skills and experience to fully comprehend the intricacies of the different countries and their requirements.

For example, most people can easily transfer funds from an account in one country to an account in another with an app on a smartphone. In contrast the investigator, to trace that money, would need to go through a lengthy procedure that can often take several years and require judicial orders to be sought and granted in very different legal systems and often translation into official languages.

There have, however, been good developments in cooperation at an operational level. There are now better avenues for states to work together on matters of mutual interest and particularly in tracing assets believed to have been looted from the state.

The International Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre is one example of such an innovation, as is the work of the International Centre for Asset Recovery in facilitating international cooperation in asset recovery cases.

Despite the importance of the Waluke and Wakhungu case, Kenya should not take its foot off the pedal. There are countless grand corruption cases at various stages of investigation or trial and each should be properly concluded. This is critical to Kenya’s global position and its post-Covid economic recovery as a destination in which investors can have confidence.

Kenya should continue to look to significantly increase its cooperation with other jurisdictions at both an operational and evidential level, continuing along this very important road and driving others to join in.

International cooperation is not a job for the impatient or the lazy. What it actually needs is an innovative mindset, for seeking agreements that respond to how we live in a digital age and acknowledge that we can work harder, smarter and more efficiently.

We need to be proactive in presenting cases that make the most of the best evidence we can obtain. Why? Because a poorly presented case that lacks crucial evidence from abroad leaves too much wriggle room for a defendant to escape.

Step by step, this progress is making Kenya a better place – and a place where one day long in the future we might be able to look back at corruption as a thing of the past.