Kuvunjika kwa mwiko, sio mwisho wa kupika ugali. —Swahili proverb

Bungoma Governor Kenneth Lusaka would like girls who get pregnant barred from returning to school.

“During our time…it was a taboo to get pregnant and if you got pregnant you even fear to go to school; you would just discontinue yourself and disappear,” Lusaka was quoted as saying.

Lusaka is right about the education of girls in the 1980s and earlier. For most girls then, getting pregnant meant the end of their education. Girls' education was not a priority for many parents. So, getting pregnant was an outright excuse—and not the reason for parents and guardians—to stop educating their daughters.

While the education of the girls who got pregnant was rudely interrupted, the community did not punish the men and boys who caused the pregnancy. It only intervened if the culprit was a teacher. The rest went scot-free—until the enactment of the Children’s Act, 2001, now Children’s Act, 2022.

If the male responsible for the pregnancy happened to be a student as was the case sometimes, the boy went on with his education.

Not all girls who got pregnant terminated their education. A few enlightened parents took their daughters back to school. Most stayed on, completing their secondary education, with some qualifying for university education.

Four categories of women define the generation Lusaka refers to. Among these women, mainly in the '70s and '80s, are those who did not get a chance to join school. Total illiteracy defines their lives—save a few who in later years joined adult education classes after marriage.

The other category is those who completed primary education but did not get a chance to join secondary school—with or without getting pregnant.

The third category is those who got pregnant along the way, but their parents accorded them the opportunity to return to school, and complete their secondary education.

The fourth category is women who joined school and completed secondary education, thereafter undertaking higher education without, as Luhya elders are wont to say, “their legs being broken.” They are very few and far between in our villages.

Suffice it to say that a multiplicity of factors was, and still is, arrayed against the education of girls. Poverty, teenage or child marriage, early pregnancy, household chores, cultural norms and practices, and menstrual cycles are some of the challenges or barriers that have denied girls access to education.

Girls from poor backgrounds formed the pool from which middle-class families secured their domestic workers. It is free primary education, which the Kibaki administration initiated in 2003, that dried up this pool. Among domestic workers were those who terminated their education because of premarital pregnancy.

In a nutshell, the girls who got pregnant discontinued their education not because of fear, but because their parents were unwilling to take them back to school.

Pregnancy should be seen in the context of the poverty of parents, and cultural practices that frowned upon girls' education. Discontinuance of education on account of early pregnancy did not discourage or prevent others from falling into the problem.

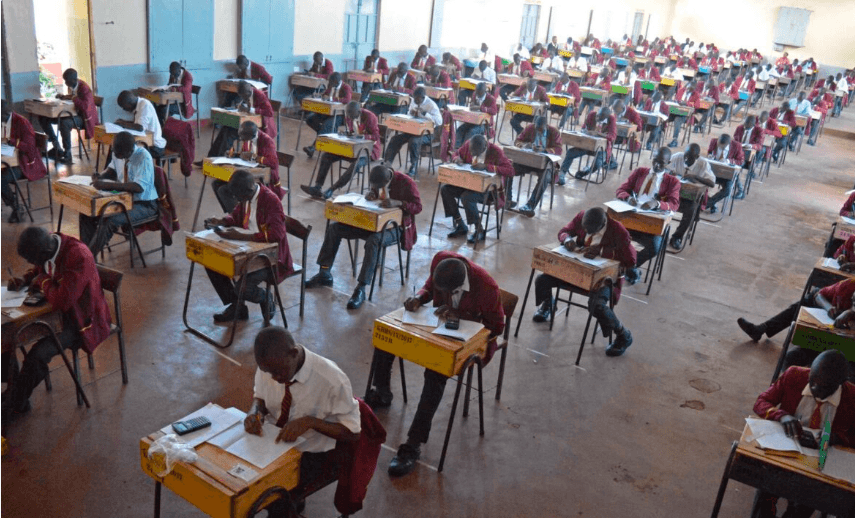

The Ministry of Education's reentry policy for learners who, for whatever reason, drop out of school, is aimed at minimising the impact of the barriers to education. The policy takes care of girls who drop out of school as well as boys.

The policy is informed by a number of considerations. Firstly, women's education and literacy tend to reduce the mortality rates of children. According to the World Bank, better-educated women tend to be more informed about nutrition and healthcare, have fewer children, marry at a later age, and their children are usually healthier.

Secondly, the reentry policy seeks to consolidate the dividends arising from better-educated women, apart from averting the burdens associated with lowly educated women. Girls are born with as much innate abilities and talents as boys. It is through education that these abilities and talents can be identified and nurtured to the fullest possible extent.

Thirdly, early pregnancy or pregnancy as a whole does not impair or erode these abilities and talents. Nor does pregnancy make it impossible for a girl who has given birth to learn. It is our responsibility to make the girl feel at ease and learn—from whichever school.

In 2014, Malala Yousafzai, in her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, said: “Thank you to my father for not clipping my wings and for letting me fly.” Yousafzai is a Pakistani education activist and the youngest-ever Nobel Peace Prize winner.

The barriers to girls' access to education have one clear effect: to clip their wings and keep them from actualising themselves. The ministry’s reentry policy, which enables girls to resume education, is meant to give them another chance, to fly and let them achieve their goals.

We should aid the girls to pursue their education and realise their goals, and not frustrate them.

Banning the girls who have got pregnant from reentering school is relapsing to the dark decades when girls were shut from school and the slightest excuse was invoked to throw out of school those whose parents had the audacity to get them into school in the first place.