As Kenya races to unlock its mineral wealth, the Environmental Impact Assessment process has never been more critical. It is the country’s main safeguard to ensure development does not come at the expense of human rights, ecological balance, or cultural heritage.

Yet recent developments, such as the EIA report submitted by Shanta Gold Kenya Ltd for its proposed open-pit gold mine in Ramula, Siaya county, reveal worrying gaps in how these assessments are conducted.

The history of EIAs begins in the United States, where they were first introduced through the landmark National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. This laid the foundation for environmental governance and inspired countries worldwide to adopt similar safeguards.

Today, EIAs are recognised under global frameworks such as the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992), the Convention on Biological Diversity (1993) and the Africa Mining Vision (2009).

In Kenya, the EIA process is legally grounded in the Environmental Management and Coordination Act of 1999 and is overseen by the National Environment Management Authority.

By law, EIAs are mandatory for projects that meet specific thresholds indicating a likelihood of significant environmental or social impacts, such as mining, infrastructure and industrial development.

One of the most essential components of a credible EIA is the analysis of alternatives. This includes the “no-project” option and alternative sites, mining methods and waste management approaches. When done honestly, this analysis transforms the EIA from a bureaucratic formality into a genuine decision-making tool.

Yet despite this strong legal foundation, the EIA for the Ramula–Mwibona project reveals many persistent weaknesses in Kenya’s extractive sector, notably a failure to assess alternatives meaningfully.

While briefly mentioning the “no-project” scenario, it ignores other viable options such as underground mining, phased development, or less harmful alternative locations. This is not just a missed opportunity but a legal shortfall.

Second, the report falls short of identifying the full social and economic consequences of displacement. More than 445 hectares of land are earmarked for acquisition, but the EIA does not say how many households will be affected, what compensation mechanisms are proposed, or how vulnerable groups like women, children and the elderly will be protected.

Equally concerning is the EIA’s vague treatment of public participation. While stakeholder meetings are listed, there is no evidence of free, prior and informed consent.

Community input appears to have had little influence on project design, turning public participation into a box-ticking exercise rather than a meaningful process of engagement.

Another red flag is the lack of clarity around the legally mandated community development agreement, which requires mining companies to allocate one per cent of production revenue to benefit local communities.

The EIA provides no details on how this fund will be governed, who will benefit, or how accountability will be ensured, raising fears of elite capture.

Globally, there are examples Kenya can learn from. In Ghana, the International Finance Corporation recognised the Ahafo South Gold Mine for demonstrating that responsible mining is possible when transparency and community engagement are prioritised.

For Kenya to achieve the same, regulators like NEMA must enforce higher standards. At the same time, communities and civil society need greater support to meaningfully influence project outcomes through access to information, legal aid and continuous dialogue.

Mining companies, too, must realise that the EIA is not a hurdle to jump—it is a process for building legitimacy and trust. Without it, even promising projects risk failure. The future of Kenya’s natural resource sector depends on restoring public confidence. That starts with an honest, inclusive and robust EIA.

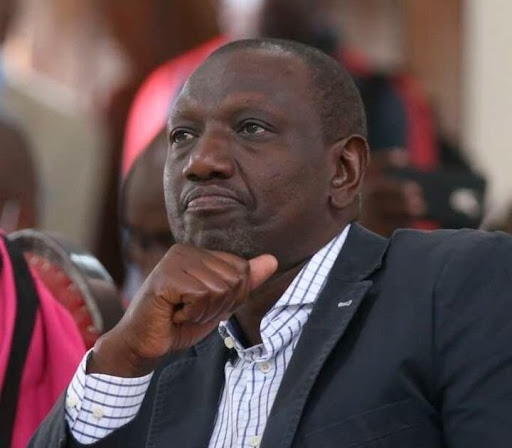

The writer is a senior programme adviser, Kenya Human Rights Commission and chair of Haki Madini Kenya