In a past article, I addressed the low export prices Kenya's teas fetch compared to China, India and Sri Lanka's value-added teas.

Let’s put this into context. Of the 6.5 billion kilogrammes of tea produced in the world, 1.4 billion kilogrammes come from India, the second-biggest producer after China’s 3.2 billion kilogrammes. Kenya ranks third with 570 million kilogrammes, followed by Sri Lanka at 252 million kilogrammes.

While China and India account for 71 per cent of global tea production, they only export 13 per cent of their production, being proof of their robust domestic markets. Kenya and Sri Lanka export about 85 per cent and 98 per cent of their production.

India and Sri Lanka export over 50 per cent of their teas in value-added form. This means teas are exported as high-value specialty teas or in final retail packaging. Kenya only exports about two per cent in value-added form, hence, the need to draw lessons from India and Sri Lanka.

India and Sri Lanka, just like Kenya, have been experiencing declining prices at their tea auctions. While the two have been worried about the increased production by Kenya, which they feel is contributing to depressing global tea prices, they are more worried about low-quality low-value teas from many producing countries. This has been worsened by the growing cost of production and cost of doing business, as well as competition from other beverages and changing consumer behaviour.

In India and Sri Lanka, value adding has been a national and deliberate effort led at the highest level of government with huge private sector participation. Indeed, it was used as a major cornerstone in the development and growth of their tea sectors.

India adopted a multi-faceted approach that included a Plantation Development Scheme to motivate tea gardens and undertaking production developmental activities aligned to quality and value addition with offers of long-term loans and subsidies.

A Processing and Packaging Development Scheme provided long-term loans to tea processing facilities.

A special Marketing Development and Export Promotion Scheme was established to increase the export markets for tea, covering market surveys, uni-national promotional campaigns, brand promotions, generic campaigns and setting up local special production units that meet target market product requirements in packaging and otherwise.

Others included a Human Resource Development Scheme and a Research and Development Scheme.

It is through these schemes that India developed a marketing strategy for her teas based on some regions of production with distinctive tea characteristics like today's well-known Darjeeling, Assam and Nilgiri. Darjeeling tea is the global 'champagne of teas', largely marketed as specialty tea. It is on record for having at one time fetched a high of Sh5,148 per kilogramme at the Calcutta Tea Auction, earning a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.

In the case of Sri Lanka, the government offered soft loans and subsidies for tea processing machinery and tea packaging raw materials for use in blending exports.

Just like India, Sri Lankan tea has over the years been marketed based on the different altitudes where it is grown—high, medium and low grown. It has been established that teas produced in the different elevational categories possess distinctive characteristics.

Sri Lanka runs a promotions bureau with offices in leading importing countries.

The country has the widest range of tea exports in value-added form, which includes flavouring, scenting, instant and organic teas.

Some of the incentives for tea value adding include tax waivers on equipment and tax holidays. Some of these date back to 1970 when they were offered to encourage the setting up of “packing companies”.

Other incentives include double deduction of overseas promotional expenses; research and development expenses; turnover tax concession on imported raw and packaging materials; concessionary financing incentives with medium and long-term credit; as well as small and medium-scale industrial loans and some refinancing facilities.

Further incentives included financial assistance to manufacturing and processing exporters to expand exports in the short term; assistance in market development and promotions; as well as advice and information on potential export markets.

We should not reinvent the wheel when surrounded by these great lessons.

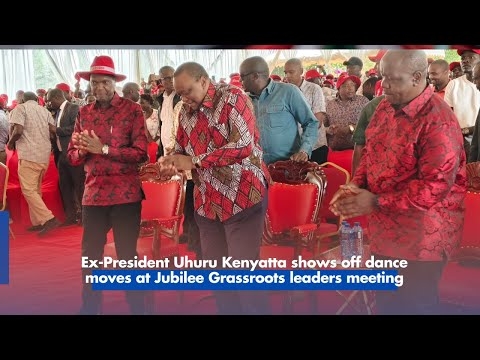

![[PHOTOS] Uhuru leads Jubilee grassroots meeting in Murang’a](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F0b2a49cd-52fb-4a92-b9dc-26e253825a4a.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)