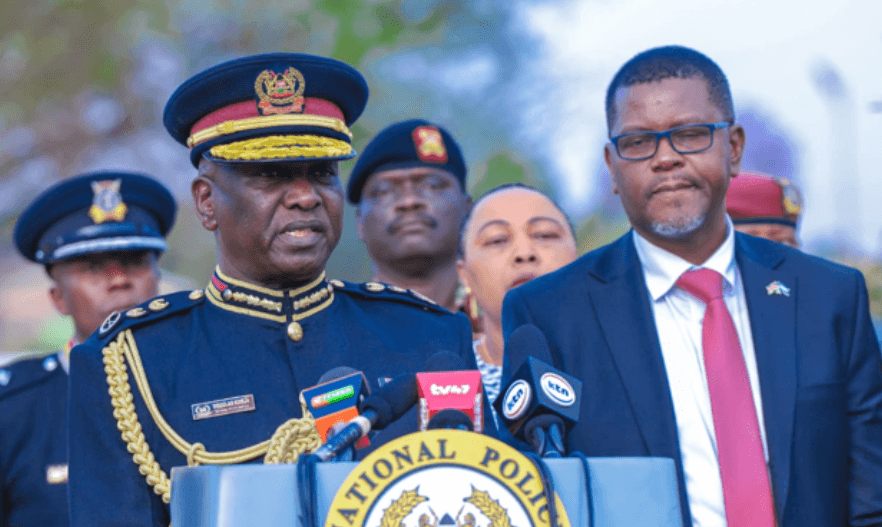

Kenya is currently transfixed on impeached Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua’s desperate legal manoeuvres to hold onto his former position.

But should we even be embroiled in endless judicial proceedings over Gachagua’s fate, when it’s clear he lacks the confidence of his boss and Parliament?

Does the Judiciary have the power to impose Gachagua on the country?

What’s clear from these questions, is that it is undeniable that Kenya’s current constitutional design leaves serious ambiguities on the dismissal of a deputy president.

It is crucial to remember that the office of the president and his deputy derives its mandate from a political contract.

The constitution does not require Kenyans to elect a deputy president directly, that choice is tethered to the president.

The president’s right to choose a deputy who aligns with his goals is essential for effective governance.

It is, therefore, reasonable to argue that a “broken political marriage” should be settled within the political domain, without judicial intervention.

While historically significant, the ongoing political divorce between Ruto and Gachagua is not where our energy should be directed.

Our country is facing larger, far more pressing issues that deserve our attention.

Official figures may claim that inflation is under control, but this is far from the reality for ordinary citizens.

The cost of basic goods has spiralled, and people and businesses are struggling to survive.

One of the most immediate culprits is the government’s backdoor approach to taxation.

After significant public opposition to the Finance Bill, we have now seen government ministries and agencies quietly introducing levies and fees to circumvent the legislature.

For instance, the cost of wheat imports has been weighed down by a steep hike in inspection fees imposed by the Agricultural and Food Authority.

Previously, importers were charged Sh3,050 per consignment, a fee that has now surged to Sh5,500 for every 40 tonnes of wheat.

This means importing 20,000 tonnes of wheat now comes with a bill of Sh2,750,000, a vast increase from the earlier nominal charge of just Sh3,050.

But that’s not the end of the story.

A notice issued by the National Biosafety Authority on October 1, 2024, introduced new fees for services related to GMOs and biosafety compliance.

Under the directive, applications for importing, exporting and transiting GMO products now face steep charges; an initial Sh10,000 for the application process and Sh50,000 per consignment for commercial imports.

Additionally, each GMO product requires labelling and certification, which costs Sh20,000 per product.

This cascade of costs on everything, from wheat to maize, disproportionately affects lower-income households, who already spend a significant portion of their income on food.

But this doesn’t just affect domestic consumption, it also impacts the exports of our farmers by making Kenyan products less competitive on the global stage.

The Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service, for instance, charges Kenyan farmers 10 times more for point-of-origin phytosanitary certificates than what their counterparts in the UK pay, and 50 times what Ugandan or Tanzanian farmers are charged.

The consequences of this are bleak.

As the cost of importing raw materials and machinery rises, businesses are forced to either downsize or shut down entirely, thus eliminating precious jobs from the market.

In my opinion, the government is failing not just in policy execution but in prioritisation.

We must build a government that supports Kenyans in their daily struggles instead of amplifying them.

Since agriculture is a devolved function, the actions of national agencies have heavy implications for our counties.

Why should the exchequer continue to fund the Ministry of Agriculture if it has ample avenues for raising its own revenue?

Their mandate, which they seem to be falling short of, is to support Kenyans through sound, effective policy.

That’s why, beginning today, I am committing to using my position in the Senate to conduct a comprehensive audit of these institutions, scrutinising whether they have served, underserved, or outright hindered Kenyans over the past five years.

As the saying goes, “sunshine is the best disinfectant”, so it’s time to shine a bright, unforgiving light on what’s really happening.

Let there be light