The Public Finance Management Act elaborates the timetable: early in the previous financial year, government departments prepare their budget plans for the next year.

The Treasury produces a Budget Review and Outlook Paper by the end of September, which goes to Cabinet and if approved, to the National Assembly.

The Treasury then prepares the Budget Policy Statement, setting out “the broad strategic priorities and policy goals that will guide the national government and county governments in preparing their budgets.”.

This must relate current plans to longer-term plans. It goes to Cabinet and then the National Assembly by mid-February. The BPS for 2025-26 has been published.

By the end of April, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance puts before the National Assembly estimates of income and expenditure for the next financial year.

Once approved, these plans become law in the Appropriation Act, which ideally would be passed by the end of June, in time for the beginning of the financial year.

Careful consideration, public participation and enough time should produce better planning, more public understanding and predictability in government practices during the year.

Supplementary Budgets undermine all this.

DEPARTURE FROM THAT PROCESS

There are two ways in which that process may legally be departed from. A total of Sh10 billion is set aside in a Contingencies Fund to meet “urgent and unforeseen need” for money; the Cabinet Secretary Finance is the judge of this (Article 208 ).

The PFMA and Regulations regulate the use of this Fund in detail. Apparently, the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) says, government agencies find these conditions too “stringent” and prefer to use the second method—the Supplementary Budget under Article 223( 1 )(a) of the Constitution.

Presumably this explains why no money was used from the Contingencies Fund even during Covid in 2020 (according to the International Budget Partnership).

It seems odd that the constraints on using a fund of only Sh10 million should be so much greater than on using the other method, the SB.

SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGETS

This article was prompted by an advertisement inviting public comment on the second supplementary estimates for the current year, comments to be submitted to the National Assembly by March 3 – merely 10 days later. Supplementary estimates – and the Act that makes them law—are designed to allow minor adjustments to the national (or county) budgeting processes.

In reality, they can significantly undermine the budget processes demanded by the constitution. This discussion draws heavily on a study of the SB process over nine years by the OAG published in 2023.

It observed that every year there are SBs, usually two and occasionally three a year. SBs are often inevitable. A new government coming into office after a general election in September may well want to make budget changes to suit their policies.

In fact the constitution does not really recognise this. The PFMA does. Serious drops in government income and rises in prices are likely to affect government spending plans.

Two Covid-induced SBs were needed in 2020. It was hardly surprising that the government changed its spending plans after the President dropped the Finance Bill 2024.

WHAT MAY AN SB DO?

The constitution deals with the most obvious risk: defining when increasing spending via an SB is allowed.

Money not allocated in the regular budget may be spent if the money allocated to a particular purpose proves not enough, or a purpose to which no money has been allocated becomes necessary.

Parliamentary approval may come later (within two months).

The OAG report points out that regulations say that new expenditure in an SB must be “unforeseen and unavoidable" and increased expenditure must be "unavoidable.”.

This seems to reflect the constitution. It adds, “Any expenditure that was known at the time the original budget was finalised should not be considered unforeseen.”

SBs “should not be used as an opportunity to alter the original policy objectives or to introduce new projects or programmes without robust public participation and the National Assembly approval.”

The report comments that there are no guidelines for government agencies on what expenditure qualifies under Article 223 and so the agencies have been seeking additional funding for items that could have been in the normal budget process.

There is, perhaps oddly, no constitutional or statutory guidance about SBs seeking to reduce or reallocate expenditure. It is surely not just the spending of money but also ceasing or reducing spending on policies and projects that should be scrutinised.

A LIMIT ON EXTRA MONEY

The constitution restricts how much above the approved annual estimates may be added by SBs to not more than 10 per cent in a year. The National Assembly may approve more in “special circumstances” and the regulations say this must be for unforeseen and unavoidable need (these provisions are confused, and I cannot go into detail here).

This was exceeded only once in the years the OAG studied.

THE PROCESS The OAG

The OAG is strongly critical. “After ten months of involvement throughout the budget formulation process, the original budget incorporates public priorities, but these are then revised contrary to what had been approved, without further public engagement.”

It said, “expenditure that would have otherwise received scrutiny by the National Assembly is approved post facto. Based on these changes, one would not be sure of the budget until the last supplementary is approved.

This undermines the budgeting process as envisaged in the Constitution.” In fact, the International Budget Partnership says that the “third supplementary budget of FY 2019/20 was approved by Parliament on 30th June 2020, the last day of the financial year.”

This makes nonsense of the idea of advance planning. Either all the money asked for had already been spent, or it could not be spent within the financial year.

There is no provision for public participation. We see this year there may be some pathetically short period for public participation and SB at the National Assembly stage. Not enough time, so far it seems, for agencies like IBP, IEA or the parliamentary budget committee to comment.

The OAG says there seems to be no clarity about what happens if payments already made are not approved by the National Assembly. This SB The current exercise is unusual because in July last year the first SB was adopted, due to the demise of the Finance Act, and most government organisations had their allocations reduced.

The figures given in the current documents are from that earlier revision. This is therefore usually less than the amount initially allocated following the supposedly thorough and participatory annual exercise.

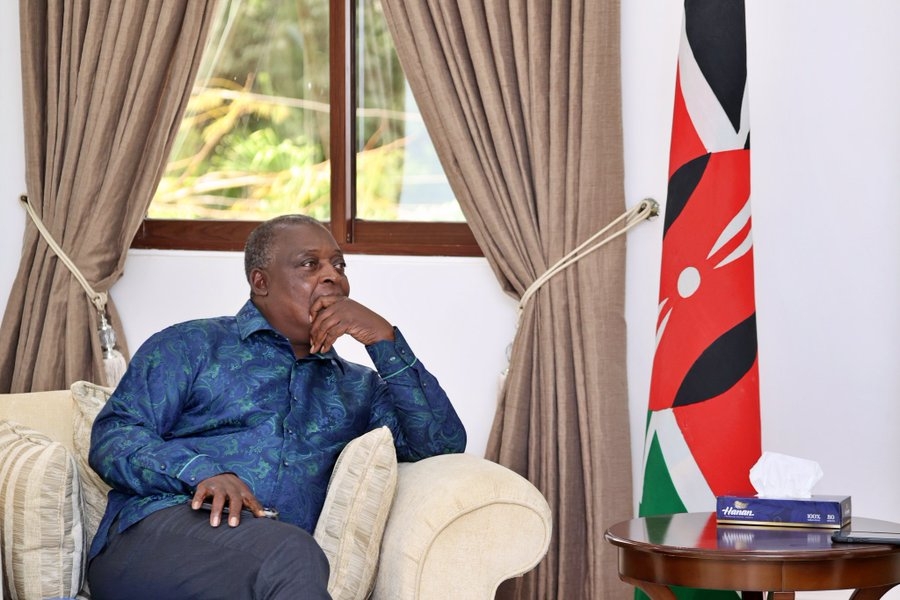

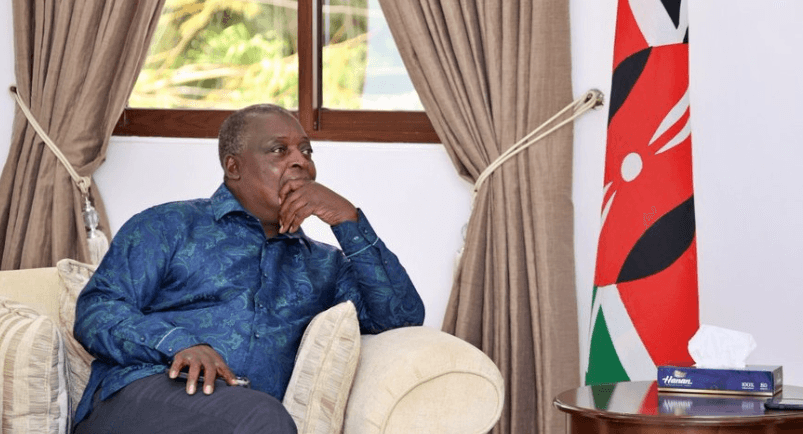

For example, in July the sum allocated to the Executive Office of the President was Sh3.5 billion, reduced from Sh5.4 billion. In the new SB it is to be increased to Sh4.2 billion. And when the State House allocation nearly doubles, this takes it back to roughly its original allocation.

Ideally the scrutiny of these estimates should be asking: how far is the financial position of government agencies to be returned to what had been originally agreed, and if some are treated differently from others, is it clear why? Including why the State Department for Gender and Affirmative Action has actually lost a little more this time round in addition to the earlier reduction, to take one example.

In the documents available online explanations are limited. An explanation that “Other changes are on account of reallocation of funds” which occurs about 20 times seems very uninformative.

A final thought: this SB is earlier

than the second SB in a financial

year usually is. Is this to be a year

with third SB? Not least, perhaps, to

deal with the fallout of the President

Trump’s executive orders?