On October 28, 2004, the National Council for Persons with Disabilities was officially appointed after the assenting to the Persons with Disabilities Act No 14 on December 31, 2003.

Ten years had passed since the Attorney General Amos Wako formed a task force led by Justice Emanuel Okubasu to review laws relating to disabled persons, with a view to coming up with an act of Parliament akin to the Americans with Disabilities Act.

It took a President Mwai Kibaki, who was sworn in on a wheelchair (due to injury) to enact the first stand-alone legislation for persons with disabilities in Kenya.

I was privileged to be appointed to serve in the pioneer board of the NCPWD by Min- ister Ochilo George Mbogo Ayacko, a 35-year-old legislator who had just been moved from the Energy docket. I was only 22 years old, and a third-year student at Kenyatta University.

I had just finished my term as a special member, one of the seven elected student leaders of the Ken- yatta University Students Association.

Dr Charles Onindo, a chemistry professor, was appointed chairman, with Lubna Mazrui, a lecturer at KU, as vice chairperson.

She declined the appointment. In fact, I was, for all intents and purposes the de facto vice-chairman.

Other board members included: Paul Njoroge Ben who later on became Senator; Hussein Borle who became an MCA; Chomba Wa Munyi (NGEC commissioner); Dr Samuel Tororei who became both a commissioner at KNCHR and at NLC; Tom Gichuhi, Musee, Nicholas Aseso, Tom Omuga, Josephine Sinyo, Ruth Oyier, Maureen Onyango (now a judge), Titus Kilika, Abdullahi Wabera, amongst others.

The pioneer secretariat was led by acting director Cecilia Mbaka, assisted by Verity Mghanga, Josephine Onyonka (deceased), Jane Wamugu, Joseph Maleu (deceased), and Fatma Dullo, who is currently the senator for Isiolo County.

Starting from the offices of the Department for Sports, Gender and Social Services that was then located at Nyayo Stadium, the council was moved to the Kabete Orthopaedic workshop on November 5, 2004.

It wasn’t an easy journey, breathing life to legislation that carried the aspirations of millions of Kenyans yearning to be heard.

This was the first time Kenyans with disabilities were being formally recognised within the echelons of government.

There were specific pieces of legislation that had been passed as private bills to establish various bodies for specific disabilities, but they weren’t government entities in the name of a state corporation.

During that period, the country was reviewing its Constitution led by Prof Yash Pal Ghai, and Prof PLO Lumumba.

We lobbied to be included in the process in terms of representation and civic education. Although attempts to have a new Constitution came a cropper with the 2005 referendum, the gains from this participation bore fruit as the 2010 supreme law mentions persons with disabilities a record 18 times.

It takes about 20 years to resolve a problem or to show results of a given endeavour. The period from 2004-24 has been phenomenal.

For a council that started with a budget of a paltry Sh7 million, to the current budget of Sh1.35 billion, this was exponential growth.

Specific funds allocated to persons with albinism and autism demonstrate the need for tailor-made interventions for certain types and categories of disabilities.

Twenty years ago, the representation of persons with disabilities in politics and in higher ranks of the Executive was considered foreign.

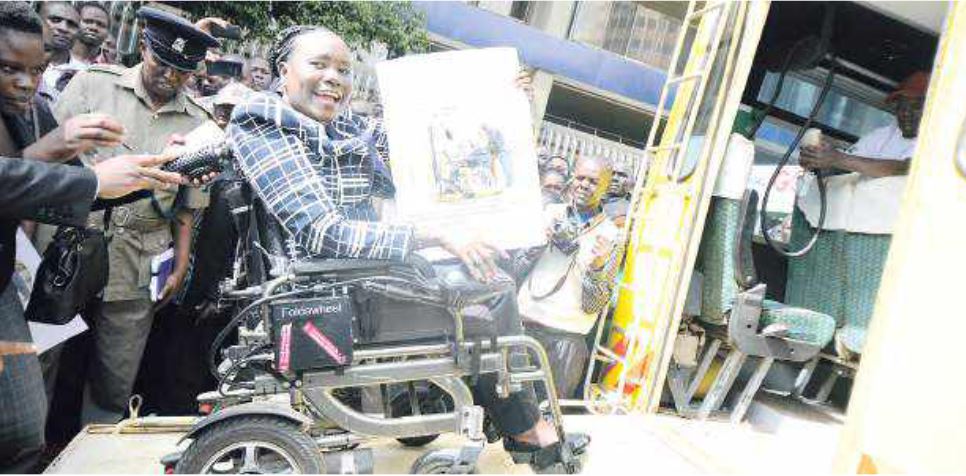

However, today, we have representation, in both Houses of Parliament, within the Executive at the PS level, and MCAs in many of the 47 county assemblies.

Some of the notables in these capacities include PS Josephta Mukhobe, MPs David Ole Sankok, Janet Teyiaa (the second Kajiiado Woman Representative) Isaac Mwaura (first MP and Senator with albinism), Bishop Robert Mutemi, Timothy Wanyonyi (third-term MP for Westlands), Sammy Leshore, Mohammed Shidi- ye, Yusuf Hassan, Godliver Omondi, Crystal Asige, Harold Kipchumba, George Mbugua, Bishop Kosgey, amongst others.

The paramilitary training at the National Youth Service, has led to the inclusion of persons with disabilities in prisons, the provincial administration and the Kenya Revenue Authority. T

he hosting of beauty contests, such as the Mr & Miss Albinism has led to the inclusion of those with albinism in public adverts on billboards and in mainstream media.

In fact, we now have Loice Lihanda, the first Miss Albinism in Kenya as a cabin attendant with Kenya Airways.

These and many other self-definition activities have gone a long way in redefining how society views persons with disabilities.

In fact, in 2017, the top KCPE exam candidate in the whole country was Goldalyne Kakuya, a young girl with albinism.

This alone shattered long-held stereotypes across the country. In sports, great athletes such as Henry Wanyoike have made people to see that disability is not inability.

There have also been appointments by various administrations in constitutional commissions that have significantly elevated the status of persons with disabilities.

Washington Sati has served as the vice-chairman of the Commission on Administrative Justice (the Ombudsman) as the first deaf person to become a commissioner in Kenya.

Dr Samuel Tororei was at one point the acting chairman of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, preceded by Lawrence Mute as a pioneer commissioner.

Others who have served in other commissions include Simon Ndubai, Twahir Mbarak, Kibaya Laibuta, Michael Mbithuka (incoming NGEC), amongst others.

In the next article, we shall delve further into the gains made so far as 20 years isn’t a short time.

Arguably,

a child born 20 years ago is possibly a

second-year student at the university.