It is quite ironic, if not coincidental, how the conversation around the shamba system erupted just when the climate change agenda was at its peak.

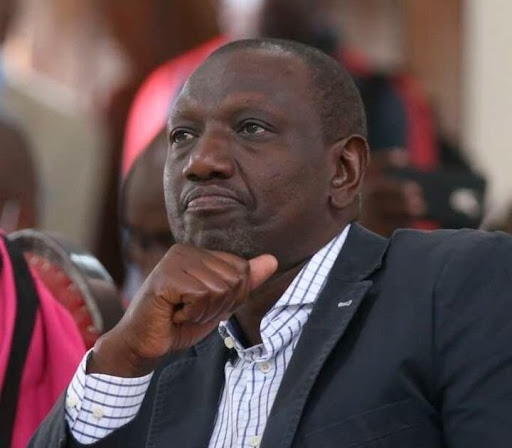

The statement by Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua on allowing Kenyans to farm in the forests can be a plus or a minus, depending on the lenses you chose to look at it with. The shamba system, otherwise referred to as Plantations Establishment for Livelihood Improvement Scheme (PELIS), has great benefits when practised well within set policies.

Such a scheme is mainly geared towards increasing forest cover and improving community livelihoods. However, it might open a window for crafty farmers to take advantage of the forest. It is also important to note, under the shamba system, people are not allowed to settle in the forest.

Forests play essential economic, social and cultural roles, yet they are being degraded at a rate higher than any other natural ecosystem.

According to the Global Forest Watch, between 2001 and 2021, Kenya lost 368kha of tree cover, equivalent to 11 per cent decrease in tree cover since 2000. There’s more to a forest than the trees we see standing.

Understanding the environmental conservation issues before delving into the shamba agroforestry system is paramount to farmers. As it stands, not all trees can be used for such a scheme. Trees that are agro-friendly, such as cordia africana and gravellia, are recommended. Unfortunately, most Kenyans are illiterate when it comes to biodiversity issues. They see nature as a mere resource to be exploited for commercial gain.

THREAT TO RAINFALL

Massive loss in tree cover will only mean an inevitable decrease in rainfall. The food we think we can grow will lack the required rain, forcing us further into the food-aid begging queues in western capitals.

For a fact, the environment does not punish the abusers of today, but rather the innocent children of tomorrow. As the government is trying to sketch a clear roadmap towards food security, there is also a need to take heed of climate change.

Kenya boasts of 5,800 thousand hectares of arable land. This is big enough to achieve the food security goal and also sustain the country’s starving areas, such as Northeastern.

The great environmental campaigner Wangari Maathai was vehemently opposed to the shamba system. She argued that allowing food production within the forest was slowly damaging the centuries-old ecosystem, no matter how many trees were planted. The Nobel laureate had a good fight against shamba systems for more than a decade, which she eventually won.

Pledging a return of the Moi-era shamba system might also call for stern awareness of environmental conservation and biodiversity. As much as the shamba system is a good idea, most Kenyans don’t have the discipline to practise it within the policies of the Kenya Forest Service.

Once the system is reintroduced, there are high chances that farmers will turn indigenous forests into farmlands, which will only harm the biodiversity. The current problem with shamba systems is mainly due to the indiscipline that has permeated every aspect of our society.

Communities are the best stewards of their natural resources. As much as KFS has an elaborate system on how to implement the scheme, many farmers are yet to understand the issues of biodiversity, climate change and environmental conservation. Also, how the whole matrix can be affected in case they go against the policies.

There's an absolute need to understand that we need our forests just as much as we need to improve the livelihoods of our communities. We need the forests for the rainwater that would help our maize to grow. The balance is very, very important.

When the awareness is well served and the system practised with discipline, it will improve the livelihoods of the people, boost the economy and save future generations from climate change ordeals.

Ian Elroy Ogonji is a science journalist and member of Mesha and Gybn