I respect my friend John Githongo’s affectionate recollection of Njonjo (and he is not alone), but not all of us have such pleasant memories.

I did not have any experience of him until after I returned to East Africa after I had done my BA in Law at Oxford University, and a Master’s at Harvard. Professor William Twining came to Harvard and asked me to teach at a new (the only) institution teaching law in East Africa, at Dar es Salaam.

Reluctantly, but out of obligation, I joined the law faculty in Dar (initially for students of the three countries but soon with inclusion of those from neighbouring states).

Perhaps because I was the only East African teaching law there, after a few years, I was appointed as the head of the faculty. I greatly enjoyed living and working in Tanzania, with wonderful students, including Willy Mutunga.

After nearly 10years, the Kenya part of the University of East Africa decided to establish its own law school. Much though I loved Tanzania and admired Julius Nyerere, I decided to move back to Nairobi and applied for a position that would have involved law school there.

I was encouraged by some distinguished Kenyans to come back home. By this time, I had already written a number of legal articles and had just finished a book with a colleague, Patrick McAuslan, on Kenya (Public Law and Political Change in Kenya, 1970).

I was fairly confident that I would get the job, given my record, and that in recent times I had been encouraged to return home (especially as all the East African colleges were becoming rather national).

I found that the Nairobi college had identified 10 candidates, with both local and overseas professors involved in the appointment.

Apparently, I was placed at the top of the list and the university planned to appoint me and I planned to come.

Alas, Charles Njonjo had seen the list of candidates — and instructed the college (which had encouraged me to apply) to throw me out — and appoint a British woman (who was not in fact appointed).

As I was packing my bags in Dar, I received phone calls from former students telling me not to come, and indeed warning me it would be unwise.

I was back to Dar es Salaam, being advised that there was no way to fight Njonjo. He had so dominated all aspects of the state.

I was never told why this happened. Many people have assumed that it was because of that book on Kenya’s Constitution that was critical of developments since Independence (as well strongly of colonialism).

Alternatively, looking back, it could have been because of Njonjo’s strong objections to Tanzania – at least Nyerere’s Tanzania. That might have played a part in a strange incident a few years before.

I had been appointed to the Kenyan Council of Legal Education (not inappropriate since most new lawyers for Kenya were emerging from Dar - they included not only Mutunga but people like John Khaminwa, Okoth-Ogendo and Amos Wako, later himself Attorney-General).

Eighteenth months after my appointment, I was removed by the AG. He may have been right that he was the one to appoint (my own book says it was the AG who would), but he could have appointed me, but did not.

His strong anti-Nyerere (and anti-the-East African ideal) attitude also explains the five cups of champagne he gleefully claimed to have downed when the Community collapsed.

So I was back in Dar – and jobless, deeply disappointed to have been prevented from taking up a job at home in such a cavalier fashion. People in Tanzania did persuade me to stay, and I concentrated on another project of great interest and value — which had its impetus from President Nyerere.

As colonies were becoming independent, he was thinking of the integration of the East African colonies as one state. He said, “There is one way to ensure in East Africa that the present unity of opposition should become a unity of construction”.

Indeed he wanted independence of these states to take place at the same time. However, his wish was not to be but his dream did not die.

As the head of the largest of four states, by including Zanzibar, he was very keen on a union. The heads of other states were less enthusiastic.

Various forms of co-operation did take place as the depth of each state increased — separately. There was some feeling that in many ways there was unity among the three states—but it weakened over time.

Mainly under Nyerere’s persuasion, I joined the community, principally as a lawyer. I was to sit at the meetings of representatives of the states.

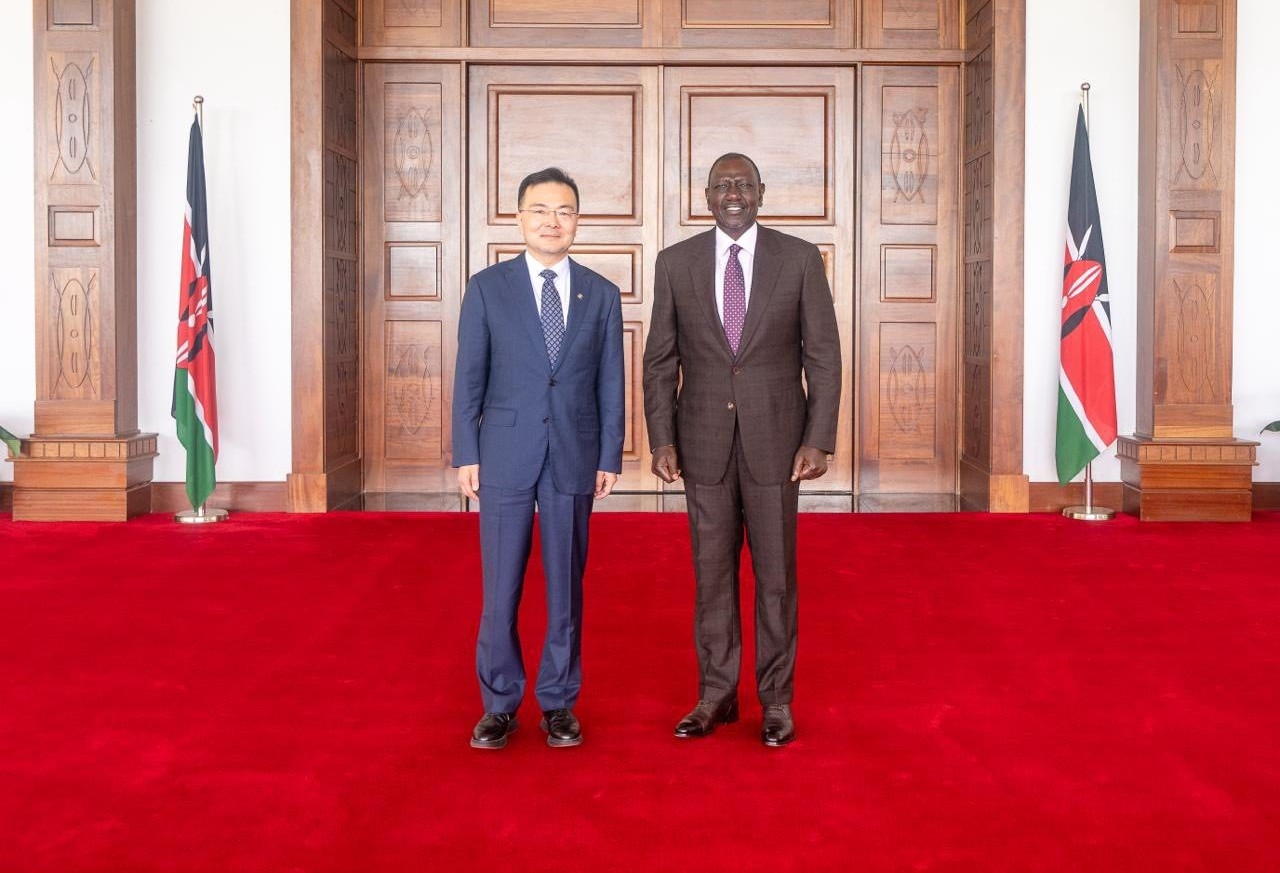

At the first meeting, Kenya was represented by Njonjo.

When he saw me, he said that the Kenya government did not want me to attend the meeting. Nyerere explained that I was there as a lawyer to help the committee.

But Njonjo said his government did not want me. At that time, I decided it was better for me to leave the meeting.

A little later I thought it was best for me to withdraw from the whole enterprise – and eventually leave East Africa - effectively for almost 30 years.

Then (Njonjo no longer being in a position to keep me out) I was approached by another Attorney General, Amos Wako, on behalf of President Daniel Moi, to return home to help establish a new constitution.

When Njongo kicked me out of the University in Nairobi, when President Moi wanted me to help with creating a new constitution, he sent a senior official to the US to persuade me to come home.

Looking back, my own experience is just an example of what Njonjo wrought. He provided the support and supposed legal backing for a state in which it was considered perfectly all right first to unpick the Constitution agreed with others at independence, including bribing senators to agree to their own abolition.

Then it was fine to create a monster of a presidency, with no effective checks and balances.

It was not a problem to undermine the Judiciary (one commentator said recently that in Njonjo’s time court orders were obeyed – but that is not difficult if you ensure that generally, courts don’t decide against the government). It was all right to detain people without trial and to order universities whom to appoint.

Kenya has paid dearly for that era and its distortions of constitutionalism. Look how our President believes he can just pontificate and it will be done (like electricity prices will be reduced). Look at the mess of a relationship between the state and universities.

A few years ago Njonjo and I coincided at a reception by the British High Commission.

Our friend, Pheroze Nowrojee, asked us if we had re-established our friendship. I am afraid that rather ungraciously — but without regret— I said there had been none.