A raft of serious questions are emerging in the sugar industry as to why the price of sugar is so high in supermarkets and other retail outlets yet there seems to more supply.

Where do retailers and supermarkets get these supplies when virtually all sugar factories in the country are operating below their capacities like the crippled giant Mumias Sugar?

If the local factories are unable to produce the commodity, why has the critical issue of massive sugar imports into the country gone unaddressed? What are the forces controlling the prices of sugar on the market and what illicit millions of profits are they taking home?

Today, Kenyans may have forgotten that in 2018 a multi-government agency raided the Rai Paper Mills, formerly Panpaper in Webuye, Bungoma county, where they recovered hundreds of thousands of tonnes of sugar equally worth more than Sh250 millions of quantities.

How many other undisclosed warehouses are stockpiled high with illegal sugar imports in Mombasa, Nairobi and other towns with huge warehouses to accommodate these? Most importantly, why has the government failed to tell Kenyans where all those tonnes of sugar disappeared to and the whereabouts of the unexposed ones?

That was just the beginning but which has kept steadily rising to continue haunting the country’s sugar market and producers to date. If the local millers are not producing enough sugar, then the government must tell Kenyans where is the excess expensive sugar was coming from if not these sources.

This also brings in the issue of mysterious disappearance of hundreds of thousands of condemned sugar from Kenya Bureau of Standards warehouses which was to be destroyed, and where it disappeared to. Could it have sparked the recent disciplinary action against Kebs' top managers and board of directors by the President?

Just before all these, immediately after Jaswant Rai entered the sugar milling business after purchasing West Kenya Sugar Factory — now Kabras Millers — things allegedly started going haywire targeting one miller, Mumias Sugar Company.

It is from this background that the deadly sugarcane poaching business eventually saw the millers' operations grinding to a total halt because it completely had no sugarcane from farmers in Kakamega and Busia counties to keep it roaring.

What baffled many was the silence by the local politicians who did nothing even as Rai continued to poach sugarcane belonging to Mumias.

At one time, the Western Development Initiative Association, a civil society group, had to side with the farmers' advocates where they petitioned Parliament through former Speaker Justin Muturi, leading to the adoption of a sugar report.

Today, most supermarket shelves in the country are flooded with Kabras and Ndhiwa Sugar brands — be it in Nairobi, Mombasa, Nakuru or Kisumu. Where does the miller get the sugar even when his own factories are either operating under capacity or grounded because of the extreme shortage of sugarcane in the country?

The high retail market price of Sh419 per 2kg packet raises extremely disturbing questions. When maize flour shoots up its simply as a result of deficiencies in supplies to millers, but that is not the case in the sugar industry.

There is also the raging battle between Jaswant and his brother, Sarbit Rai of Sarrai Group over the running of Mumias Sugar Company. The two are embroiled in bitter corporate wars over the company where Jaswant is having more than casual interests.

To show just how messy the sugar business is, and what Mumias Sugar Company is facing, its directors have been charged of contempt.

The Court of Appeal judges recently gave a stay order until September when the case shall be ruled and Mumias Sugar company will have to stay grounded.

This declaration means that one party has been granted powers to continue destroying the sugar industry and pocketing billions of shillings daily at the expense of the Kenyan consumer. This is simply because he has no competitor and he may as well be dictating the current sugar prices against her competitors.

As a matter of fact, it is long overdue that any government machinery should take microscopic study and action after exposing the truth to the Kenyan public.

There is also the question of supermarkets selling packets of sugar in their own brand names? Do they mill sugar to brand it as their own? Where do they get that sugar to be able to execute that with comfort? We are talking about major supermarkets — right from Nairobi, Mombasa, Nakuru, Kisumu and virtually all the county headquarters.

It is even getting complicated when Trade Cabinet Secretary Moses Kuria announced granting authority to the Kenya National Trading Corporation to import sugar, fertiliser and oil. Why so when his Agriculture colleague has failed to tell Kenyans how the government is going to solve once and for all the crisis in the sugar industry?

The other critical questions are whose interests will these businesses be serving? Who are the powers controlling that state corporation, both directly and indirectly, and whose interests do they serve? Definitely not the Kenyan public.

Instead of addressing the most critical issues strangulating the country’s sugar industry, the government is already opting for imports. What does this tell consumers? The end result is that the whole business, instead of getting sweeter and delicious, will only get murkier because of the current free for all situation.

All these are happening when the 'Report on Crisis Facing Sugar Industry In Kenya' that was adopted by Parliament in 2015 is yet to be implemented seriously.

The report was followed by the former Kakamega Governor Wycliffe Oparanya-led task force on sugar woes and the Wamunyinyi Sugar Bill. All these interventions need serious attention and action but, instead, are now hampered by the power play of monopoly seekers.

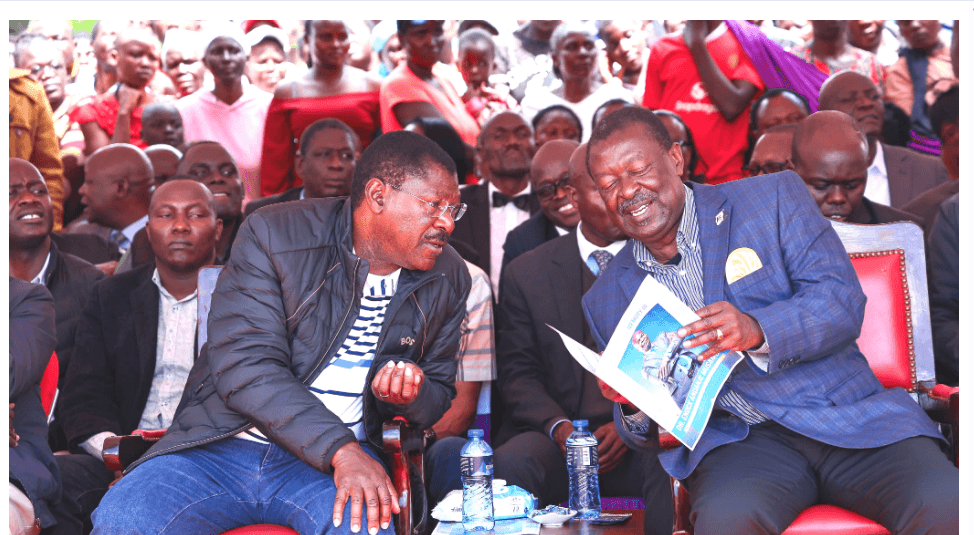

Eyes are now on Muturi, who as the Speaker of Parliament, played a key role in protecting the interests of the sugarcane farmers.

Journalist and media consultant