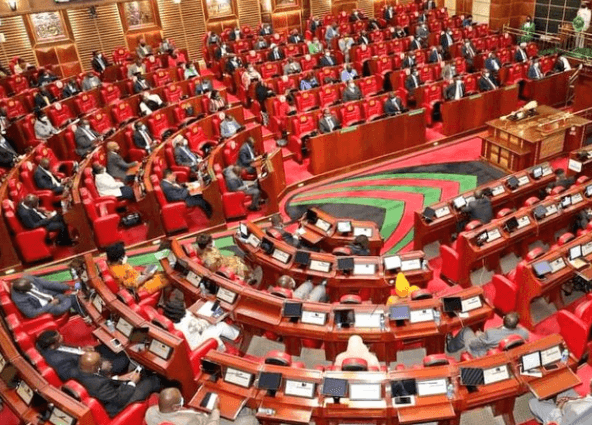

A few weeks ago, the Senate expressed displeasure against what it perceives as a deliberate move by the National Assembly to undermine its legislative mandate.

The disquiet followed the National Assembly’s alleged trend of frustrating Bills originating from the Senate. The latest Senate Bills to be dropped by the National Assembly at the Second Reading include the Employment (Amendment) Bill, 2022 and the Natural Resources (Benefit Sharing) Bill, 2022.

The recent fallout is reflective of a trend that has characterised the relationship between the two Houses of Parliament since 2013. Disagreements have manifested in various ways and have played out in different forums and platforms.

A couple of times, the Judiciary has been invited to mediate the differences between the two Houses. In October 2020, for instance, the High Court declared over 20 laws unconstitutional on the basis that the Senate was not involved in their processing.

The matter found its way into the Supreme Court, following the Court of Appeal’s decision to overturn the High Court’s decision. In its wisdom last year, the Supreme Court allowed the two Houses room to settle the tussle on their own. The directive leveraged a desire by both the Senate and the National Assembly to settle the persistent differences amicably.

Legislative intervention is the latest in the list of interventions suggested to address the standoff. The Houses of Parliament (Bicameral Relations) Bill, 2023, by the National Assembly is intended to streamline relations between the two Houses, particularly in the process of developing laws.

It is a worthy effort, only if it can truly and realistically address the protracted problem. A look at the Bill however raises doubts on its capacity to achieve that.

The challenge facing our bicameral Parliament is fundamentally a design one. Looking back, the adopted design of our bicameral Parliament is fundamentally flawed. Confining the role of the Senate almost entirely to devolution set the stage for the persistent chaos we continue to witness in the management of parliamentary affairs.

It is baffling why the Senate’s role is majorly framed around devolution, yet county assemblies are established to oversight the devolved units. The design flaw has yielded a two-fold problem for the Senate: Fighting for space at the national legislative table and crowding out legislative and oversight space of the county assemblies.

Manifestation of the former is partly in the numerous court cases that the Senate has had to file to secure its space. A case filed by the Council of Governors in 2014 challenging the Senate’s role in summoning them (governors) is a clear demonstration of how the Senate is crowding out the county assemblies’ space.

The Houses of Parliament (Bicameral Relations) Bill, 2023 does very little, if any, to address the fundamental flaw. In any case, it only serves to refine and entrench certainty of the very constitutional design flaw. There is hardly anything new that the Bill seeks to address that is not provided for in the Constitution.

Even if passed, it is quite unlikely that it will put to rest the tensions triggered by the unbalanced National Assembly-Senate power relations, which largely favour the National Assembly. Originated by the National Assembly, it is even doubtful that the Senate will embrace the Bill in the first place.

Addressing the flaw requires much more than a legislative intervention. It requires a fundamental re-look at the Constitution itself. A desirable constitutional amendment should expand the Senate’s legislative locus to include some of the functions currently reserved exclusively for the National Assembly.

Such change would foster checks and balances between the two Houses as happens in other comparable jurisdictions such as the US. Parliament may want to take a look at the comprehensive audit report by the Office of the Auditor General published in 2016.

Among other things, the Report of the Working Group on Socio-Economic Audit of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010 impressively documents the deficiencies afflicting Parliament as currently designed. Its recommendations go deeper than the current Bill provides.

Phd candidate at the University of Nairobi’s Political Science and Public Administration Department. [email protected]