Various officials of government have been telling us, “We must live within our means.” Among various natural reactions, including “deal with corruption” and “cut the wasteful spending” one was very prominent on X (formerly Twitter). It was something like, “It is ironic that our political class gets away with high salaries, ridiculous allowances, and unnecessary extravagances while so many Kenyans are unable to put food on their tables.”

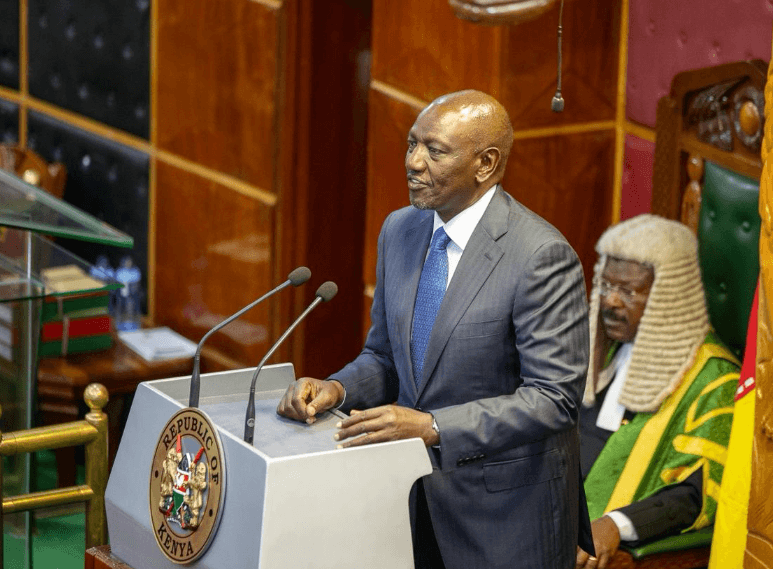

I have particularly wondered what the President (gross salary Sh1,443,750, including house allowance), a Cabinet Secretary (gross salary Sh990,000) and the Chair of a constitutional commission (gross salary Sh792,519) mean when they say the country must live within its means.

I am not arguing for any particular approach, but want to explore what the Constitution says about fixing and funding of public sector salaries – focusing particularly on reducing salaries. I use “salaries” for short to include the various other elements of remuneration, particularly allowances.

The Constitution

The drafters of the Constitution made a choice to take the power to fix public sector salaries away from MPs. It is the clearest conflict of interest for MPs to be able to fix their own salaries – and avoiding conflict of interest is a fundamental principle of Chapter Six on Leadership and Integrity.

Now the Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC) fixes the salaries etc. of state officers (members of the executive at the national and county levels, legislators, members of independent commissions, judges and magistrates and a few others). MPs especially have resented this, and the Parliamentary Service Commission has been successfully sued for trying to increase allowances.

The SRC advises on those of other public officers, but ultimately the governments make those decisions.

The SRC is directed by the Constitution to consider whether the total payable for public salaries is “fiscally sustainable” (something the government seems to be telling us it is not), yields “productivity and performance” and demonstrates “transparency and fairness” (Article 230). Another consideration does not apply to state officers: “the need to ensure that the public services are able to attract and retain the skills required to execute their functions”.

There is also the general provision that “public money shall be used in a prudent and responsible way.”

There is absolutely nothing in the Constitution that would make it impossible to reduce as well as increase salaries and other benefits. But the Constitution and the law must still guide the process.

In 2017 the SRC tried to reduce the allowances of MPs, but ran into difficulties because of procedural issues. Justice Odunga held that the SRC had not carried out a study at least a year before, including the economic situation, and a comprehensive job evaluation. This was required by the Regulations the SRC had itself prepared.

Two types of reduction

A body that fixes salaries might wish to reduce them in basically two situations. My point is that courts – which are not supposed to decide what polices are wise, just what is lawful or constitutional – need to take the context into account. The principles guiding the two types of reductions might be rather different.

In a financial crisis situation it might be thought necessary, or at least a useful contribution, to reduce salaries temporarily - pending a return to better financial times. In the biggest financial crisis in the 20th century – the Great Depression beginning in 1929 – governments did just that. In the UK many public sector salaries were cut by 20 per cent less for lower salaries. And in the recession of 2008-09, many countries cut public sector salaries. I am not advocating this – such measures are necessarily controversial – just looking at the law.

Among the principles that would be relevant would surely be that generally the impact on public sector employees should be spread evenly (the constitutional principle of equality). However, some exceptions to that would be justified. First the most vulnerable – basically the lowest paid – should probably be exempt from the cut or at least suffer a lesser cut (the principle of equity). And second, perhaps, those who make this decision might suffer among the heavier cuts, for reasons of getting public buy-in.

A financial crisis is something that needs a rapid response. If you can’t reduce the way money is spent by the public sector on projects and “development”, or recurrent expenditure of a non-salary sort (like trips) it may be necessary to increase taxes – which is what we have been seeing the government do recently.

Indeed, when the wage bill is a very high proportion of national expenditure, reducing salaries may be the only way – other than sacking some staff. A salary freeze is possible – but slower to have an impact. The choice may be between some people suffering financial difficulties for a while, and other people dying – e.g., for want of drugs.

The other possible situation is when it has become clear that some people are actually being paid more than is justified – particularly within the constitutional principles. The element of urgency is less and courts would reasonably require more elaborate observance of provisions like Article 47 C fair administrative practice – and public participation.

In fact, the SRC seems to have restricted its own abilities by the regulations it made under its Act. The assumption seemed to be that things would always be rosy and the commission’s task would be by how much to increase salaries, etc. There is even a regulation that state officers are entitled to an annual increment.

The Commission seems to have become aware of such issues and drafted a new set of regulations in 2022. These do not require a study a year before any review. Nor is there any provision for an annual increment. And the possibility of a situation of some urgency was imagined and the draft provides that the Commission might “undertake a special review of the remuneration and benefits of State and other public officers to address emerging circumstances and conditions”. However, the National Assembly rejected these regulations in June 2023.

The Judiciary

This brings us to an interesting issue: if you could reduce the salaries or other benefits of state officers, could you do the same for the judges?

The answer is – it would be very hard. The Constitution says, “The remuneration and benefits payable to, or in respect of, a judge shall not be varied to the disadvantage of that judge.” This is generally agreed to be important to avoid any risk of a judge being penalised by the state for a decision it does not like.

There is an interesting history to this in Kenya. Earlier draft constitutions spoke of “members of the Judiciary” or “judges”. The current wording did not appear before the final draft.

Why did the Committee of Experts change to “a judge”? Did they mean that one or a few individuals’ salaries could not be reduced, but a wholesale reduction of judicial salaries was not prohibited? Or that any individual’s or any number of individuals’, or even all the judges’ salaries cannot be reduced? Almost certainly the judges will decide the latter if it comes to court. It could have been clearer.

The question has arisen in countries without an explicit constitutional prohibition on salary reduction. The Canadian Supreme Court said the salaries could be reduced provided that this affected all judges or all of a class of judges, and an independent commission made the decision. Kenya does have such a commission, of course.

In the 1930s in the UK (with no written constitution), the Judges fought hard to resist their salaries being reduced when the public sector salary generally was. One distinguished author wrote of this “squalid incident”, saying: “It had not reflected well on the judges. They had appeared selfish and out of touch with reality.”

Our Constitution probably protects our judges. But do other state officers, with their generous salaries and allowances, ever wonder if that last sentence might fit them?