Kenyan politics has been dominated by two tribes since independence: the Kikuyus and Kalenjin. All five presidents we have ruling the country have come from those two tribes, with the Kikuyus having the upper hand, having placed in the State House three of the five presidents.

This is not by accident but by design on account of our history.

When it became apparent that Kenyans could not stand colonial oppression and rule anymore, a few men and women, mostly Kikuyu, got together and said the white man must go. The white man responded with even more brutal force and abuse of those rebelling, officially crushing the Mau Mau movement in 1956.

Although tens of thousands of mostly Kikuyu fighters, including Dedan Kimathi, lost their lives and others like Jomo Kenyatta languished in jail for years for playing key roles in the Mau Mau movement, the idea of freedom from oppression and abuse had caught fire throughout Kenya and in time, the white man was forced to give up and grant us our freedom.

This was our First Liberation.

If Kenyans thought they had freed themselves from the yoke of colonialism and had arrived in Canaan with the swearing-in of Kenyatta as our first president at independence in 1963, they soon would find out they had merely switched from oppression by the white man to oppression and abuse by their fellow Kenyan.

Oddly, though, even as Kenyatta was exercising enormous power over the entire nation, cowering everyone and suppressing all human rights in a markedly oppressive manner, the country was doing well economically, with the fastest economic growth occurring between 1969 and 1974.

Not all Kenyans were benefitting from economic activity, however.

The gap between the rich and poor grew, thanks to increased corruption and concentration of wealth among mostly those around Kenyatta or within a sniffing range.

When progressive and compassionate politicians demanded that Kenyatta account for the disparity in prosperity in the country or at least take measures to reduce corruption and attempt to reduce inequalities, they were either intimidated to silence or simply had their lives snuffed out, as was the case of JM Kariuki’s assassination on March 2, 1975.

By the time Kenyatta passed on in August 1978, Kenyans had basically resigned to being oppressed and accepted the status quo.

Then came one Daniel Moi, our second president.

To say Kenyatta’s regime was oppressive, corrupt to the core, unresponsive to the people’s needs, greedy in land-grabbing and undeterred in the commission of other economic and political injustices would be leaving nothing to say about the Moi regime other than to say it was 10 times worse.

So much so that after two months, Moi, with a hapless Parliament, amended the constitution to officially make Kenya a one-party state. This was followed by the failed 1982 coup.

As was the case during the Mau Mau movement, however, the coup attempt reignited people’s passions and quest for freedom once again and, thus, the birth of the Second Liberation.

So determined was the country in ridding us of Moi that when he attempted to shove down our throats his project Uhuru Kenyatta in 2002, the country soundly rejected the move and, instead, overwhelmingly elected Mwai Kibaki as our third president.

Uhuru would, of course, become president in 2013. In the irony of ironies, much as he was rejected in 2002 as Moi’s project, Uhuru was not only rejected by his own community for supporting Raila, but his successor cleverly exploited his weaknesses and faults in Raila’s campaign to see himself sworn into office as our fifth president.

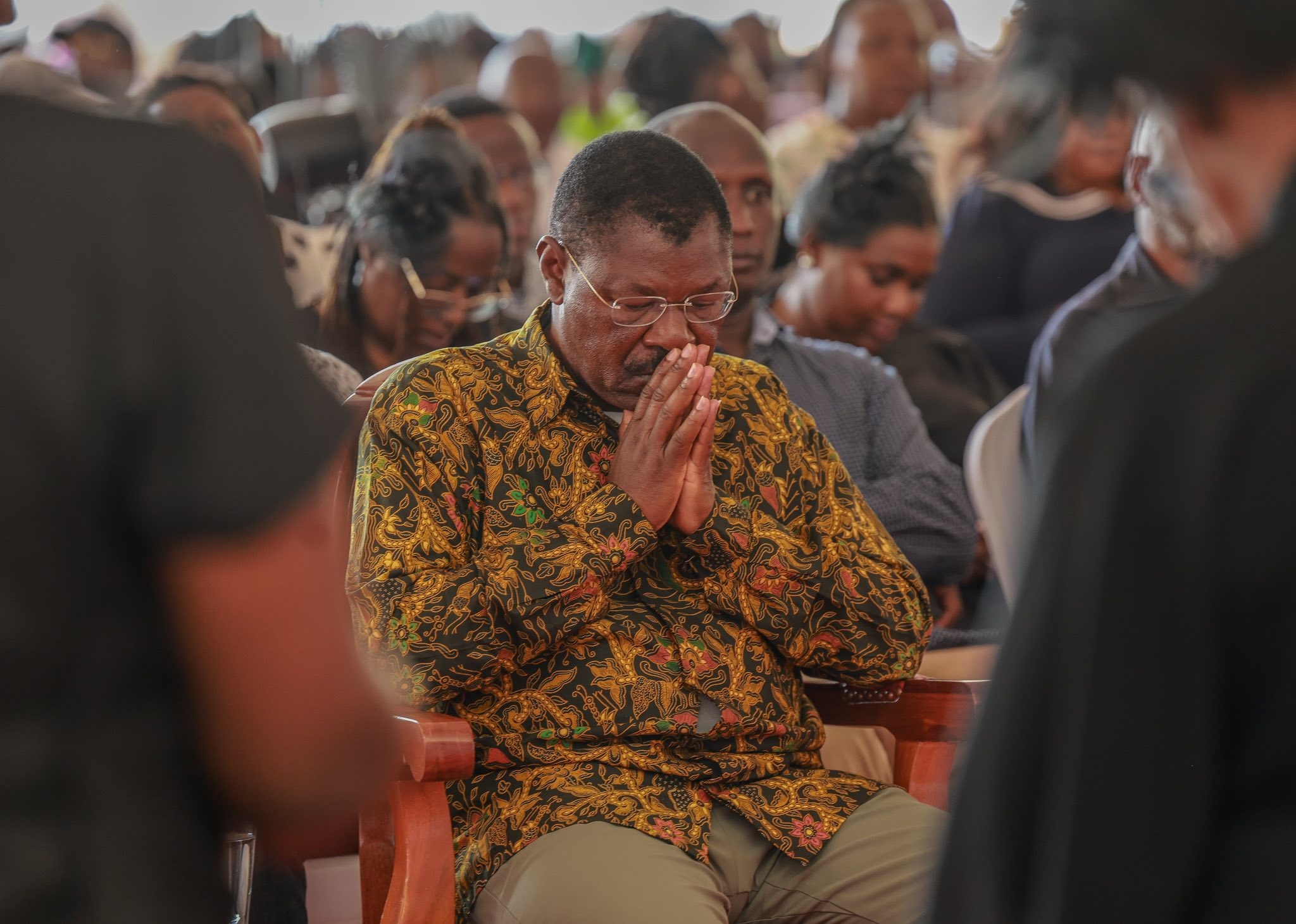

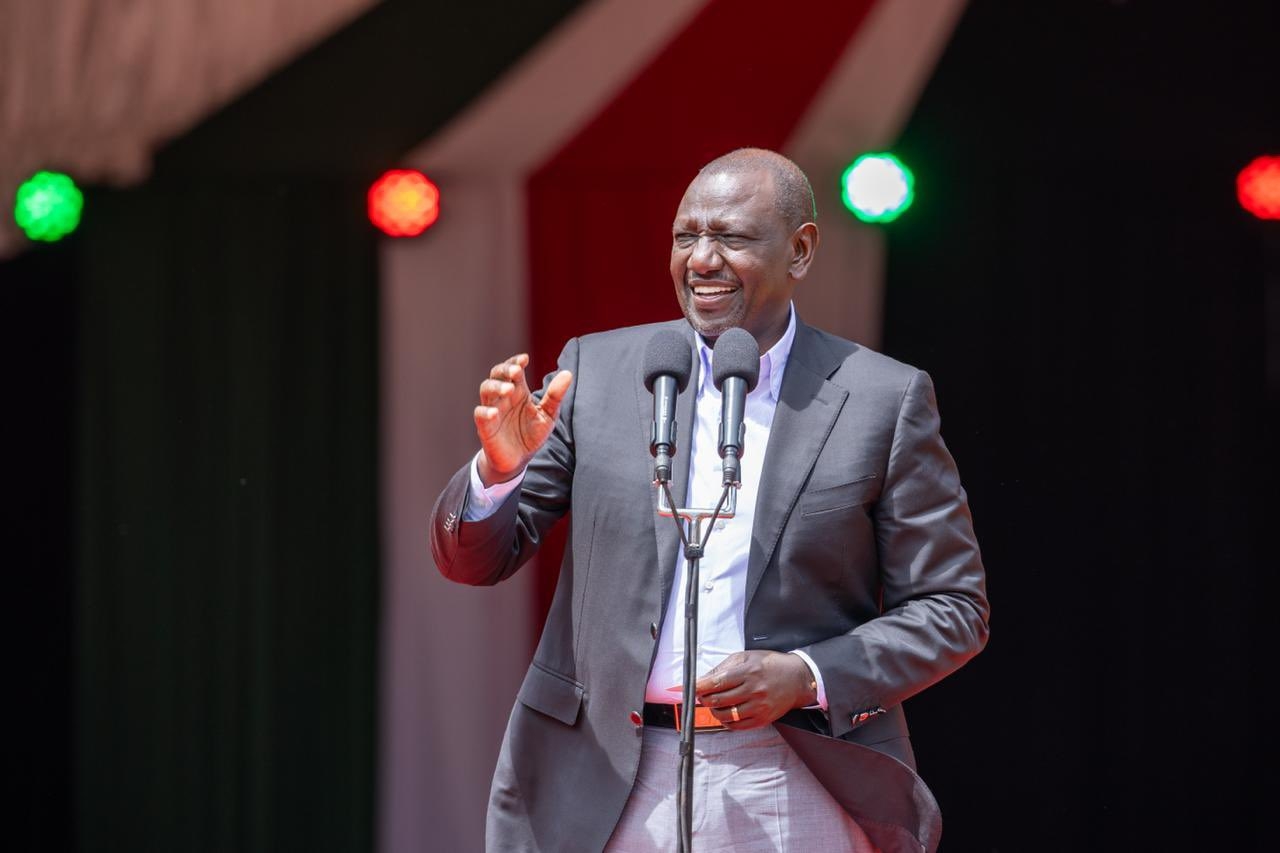

Less than two years into his presidency, and amid widespread disapproval of his leadership, Ruto now is believed to be engineering a strategy to simultaneously accomplish two gigantic quests: demolish the House of Mumbi as a dominant political force and usher in a new generation of youthful leaders who shall forever be indebted to him.

Quite a mission, but as I’ll explore in my next piece, it is a strategy prone to opportunity and peril.