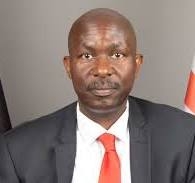

You may have wondered about a statement in Parliament during the recent process of confirming the nomination of Douglas Kanja as the new Inspector General of Police.

Apparently, he has reached the usual retirement age for police officers. But this issue was dismissed on the basis that it does not apply to “state officers”.

The public service, and the police services generally, are supposed to retire at age 60.

But universities have had different retiring ages from each other.

In Kenya and other former British colonies, colonial civil servants retired at age 55.

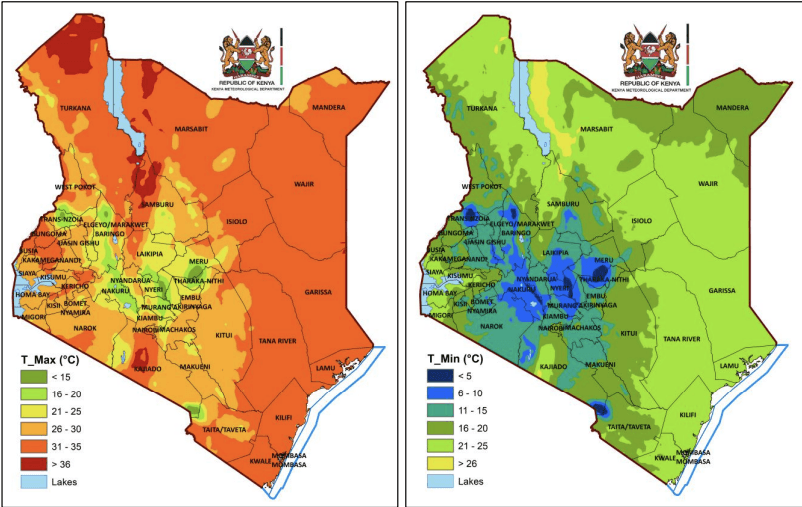

The view was that they needed to retire early because of the stresses - climatic and perhaps others like disease.

That age was, in Kenya, raised as recently as 2009 to 60 (except for workers with disability who may work until 65).

State officers

The IGP (and the two Deputy IGs who head the Kenya and the Administrative Police Services) are indeed “state officers”.

So are elected officials, members of national and county government executives, judges and magistrates, principal secretaries, the officers heading the KDF and its individual services, and members of commissions and holders of a few other specified offices (Attorney General, Auditor General, Controller of Budget and DPP).

The concept of “state officer” first appeared in the Bomas draft Constitution. Its significance in the Constitution as adopted - apart from carrying some sort of cachet, I suppose, is that the famous, though of limited success, Chapter Six on Leadership and Integrity, applies only to state officers, though its principles must be extended to other public officers.

State officers’ benefits must be fixed by the Salaries and Remuneration Commission (which merely “advises” on those of public officers).

In 2013, MPs tried to amend the Constitution to remove themselves from the list of state officers - precisely to restore their previous power to fix their own salaries.

State officers limited hold on office

It is true that state officers generally are not subject to the age-related limits that public servants generally are. But not every situation is the same.

Only judges are given a constitutional retirement age of 70, but they may retire any time after they reach 65.

The judges of the US Supreme Court have no retiring age still.

And some may hang on well beyond an age that is good for them and probably for the law, to prevent a new President from replacing them with someone politically unpalatable to them. In the UK, the age was recently raised from 70 to 75.

Before 2010 Kenyan judges’ retirement age was 74 – fixed to enable Sir James Wicks to remain in office so he could continue to give government-friendly judgments.

After 2010, some judges challenged the new rule in the Constitution. They failed and all had to retire at 70.

Magistrates, though state officers, have no constitutional retiring age and retire at 60.

Quite a number of state offices have terms limited by time period not age. What is the motive?

Age limits are designed to prevent people from working beyond their effective age, perhaps to make way for the next generation, and also to form part of the framework for people to retire with a well-earned, but sustainable, pension scheme.

Term limits, on the other hand, are designed to prevent people from getting too entrenched, over-influential, and even corrupt.

Age limits are clearly a form of constitutional discrimination. Many countries have considerably reduced mandatory retirement discrimination. Although age discrimination is unconstitutional (unless for good reason), a constitutional provision for discrimination cannot be challenged.

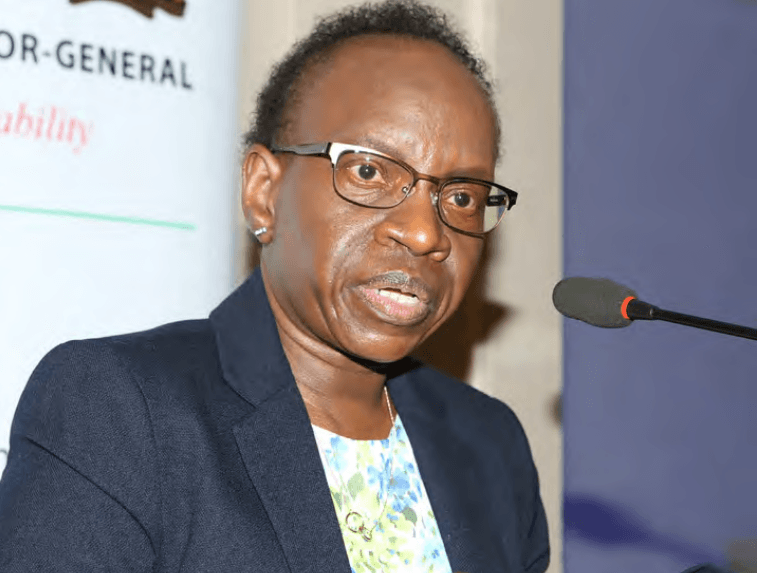

The Controller of Budget and the Auditor General each have a single term of eight years (Articles 228 and 229 (3)), as does the DPP (Article 157(5)). A member of a commission or an independent office holder have a “single term of six years” (Article 250).

Although the Controller of Budget and the Auditor General are the only “independent office holders”, we have to assume the drafters specifically intended them to have the eight-year terms. Unhappy drafting, though.

Members of the Judicial Service Commission elected by their interest groups – like a court or the law society - have an initial term of five years but may be elected for a second term (Art 171(4)). This presumably is justified because of the democratic choice element.

The Chief Justice has a single term of 10 years as such, but might have to retire early because of the age limit (Art 167(2)).

The first two CJs under the new Constitution did retire before serving 10 years, the current one could serve the full 10 years

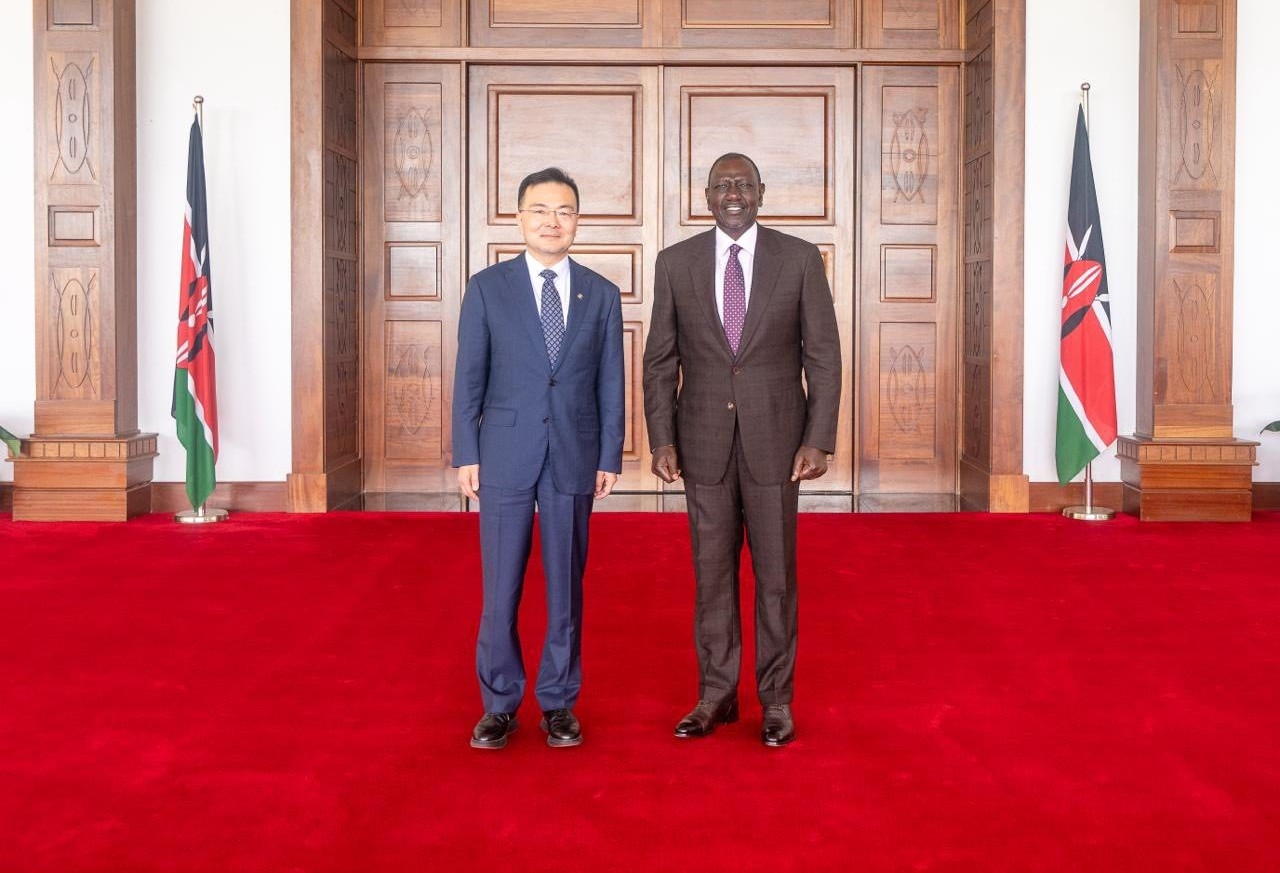

The IGP is appointed for a single four-year term (Article 245(6)). The Constitution does not fix a term for the two Deputy IGs.

The military heads’ terms are specified not in the Constitution but under the Kenya Defence Forces Act.

They serve for four years (but must leave earlier if they reach retirement age during the four years), but the President may retire them before the four years end.

Presidents and governors, of course, have a limit of two terms of five years - to which they must be elected. The first official draft constitution (Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) in 2002) fixed an age limit for president – a minimum of 35 and a maximum of 70 at the date of nomination (but this could have enabled someone to be President until almost 80!).

The background to this included the recommendation of the Kenyan medical profession: that beyond a certain age, people, though they may be healthy enough, are more vulnerable to impacts of ill health and other factors, and in reality are not generally as effective as they were. You might think that political developments in the US give some support to this view. Possibly even closer to home?

Mwai Kibaki, who turned 70 in 2001, hated this idea – even though he was assured that it would not apply to him for a single bid to be elected under the then draft Constitution.

However, in the event, he was not satisfied with a single term – elected in 2002, he stood again in 2007.

But the Bomas draft (National Constitutional Conference) had removed both upper and lower age requirements (MPs had more influence over the Bomas draft than the CKRC draft) and had anyway not been adopted

Among state officers MPs (and MCAs) are among the least restricted. Of course, they have to be elected for a term of usually five years.

There is no legal limit to how many terms they can serve. Nor to their age. The oldest Kenyan MP in 2022 was 75 years old.

Limits on terms of legislators have been adopted in a few countries and mooted in many.

Confusing?

The Constitution drafters felt that the elderly were almost by definition in need of “reasonable care and assistance” and fixed “elder” as meaning over age 60. And public servants generally are expected to retire at that age.

But somehow people in politics, or people who get to senior positions in public service, are assumed to get a new lease of life. In the case of judges, this fades away at age 70 (magistrates don’t get it at all).

And being Chief Justice does not give one the extra boost of energy or ability that people are apparently assumed to get by becoming a member of a commission or a holder of an independent office.

One can imagine that being head of a security force is less physically demanding than being on the beat or the front line. But here too we have a difference – between the police and the military.

Part of this difference relates to the reluctance to try to bring the military under constitutional control – but giving the President greater control.

Is there really any rationale for these differences?