Lately, there has been labour unrest especially in the academic community, including the teaching fraternity. The most visible and cyclic have been by the lecturers.

Analysts opine that the trade unions will soon become obsolete, owing to changing times in the management of human resource in the workplace.

The digital age and the entrenchment of big data analytics in management has dramatically altered the dynamics of organisational management and leadership.

Trade unions in the developing world and especially in Kenya have not kept the pace of the transformation. The leadership of the unions appear stuck in the old mould of agitation for improvement of the workplace environment.

This will render them irrelevant and unnecessary in the workers’ representation. The labour movement has its roots in the industrial revolution in Europe.

Labour became a critical component and factor of production. However, because of mechanisation of production processes, labour required to be retooled through acquisition of skills to operate the machinery.

The demand for skilled labour posed a direct threat to the existing workers. Industries declared redundancies and arbitrarily laid off excess and irrelevant staff.

The ensuing unrest led to industrial tension, most times bringing the operations to a halt. Industry owners could not afford prolonged closures and the workers as well could not persevere for long periods without pay.

At the same time, there was radicalisation in the political environment.

The socialist movement was taking a firm rooting with calls to the dictatorship of the proletariat. The communist manifesto was published and it delineated society as class stratified.

It demonstrated the domination of capital over labour. It thus advocated for the hostile relationship between capitalists and workers.

The confluence of interests between the workers and commoners threatened the status quo and good order. Business was going down and the aristocracy was being dismantled.

Therefore, to return to normalcy, the political order was reorganised to establish the House of Commons to act as the peoples’ representatives.

The House of Lords was retained to act as the guarantor of the monarchy’s privileges. At the business level, workers were allowed and encouraged to form trade unions.

This would enable them to engage with business leaders strategically in agitating for their rights and welfare. The process was expected to be civil and with dignity.

But because of their close association with the socialist political class, their engagements with management were antagonistic and most times turned violent.

The socialist political leadership established in Eastern Europe in the early 20th century exploited the workers’ plight. Needless to say, the ensuing rulers continued to exploit the masses and workers as they created political dictatorships.

The existing mutual suspicion between trade unions and the ruling class was a feature of the colonial governments in Africa and Kenya in particular.

The workers viewed the colonial government as an appendage of the white settler community, who at the time controlled the means of economic production.

Things were not helped by the fact that majority of the elite of the society were themselves workers. They therefore naturally found themselves on the side of the agitation for political freedom.

Using the socialist models, they became abrasive and violent in their demands for better working conditions. The repressive response from the colonial governments only helped to aggravate the situation.

The workers’ approach and the government’s response solidified the relationship between the nascent independence movement and the budding trade unions.

They had a common enemy in the white settler community as well as the colonialist government.

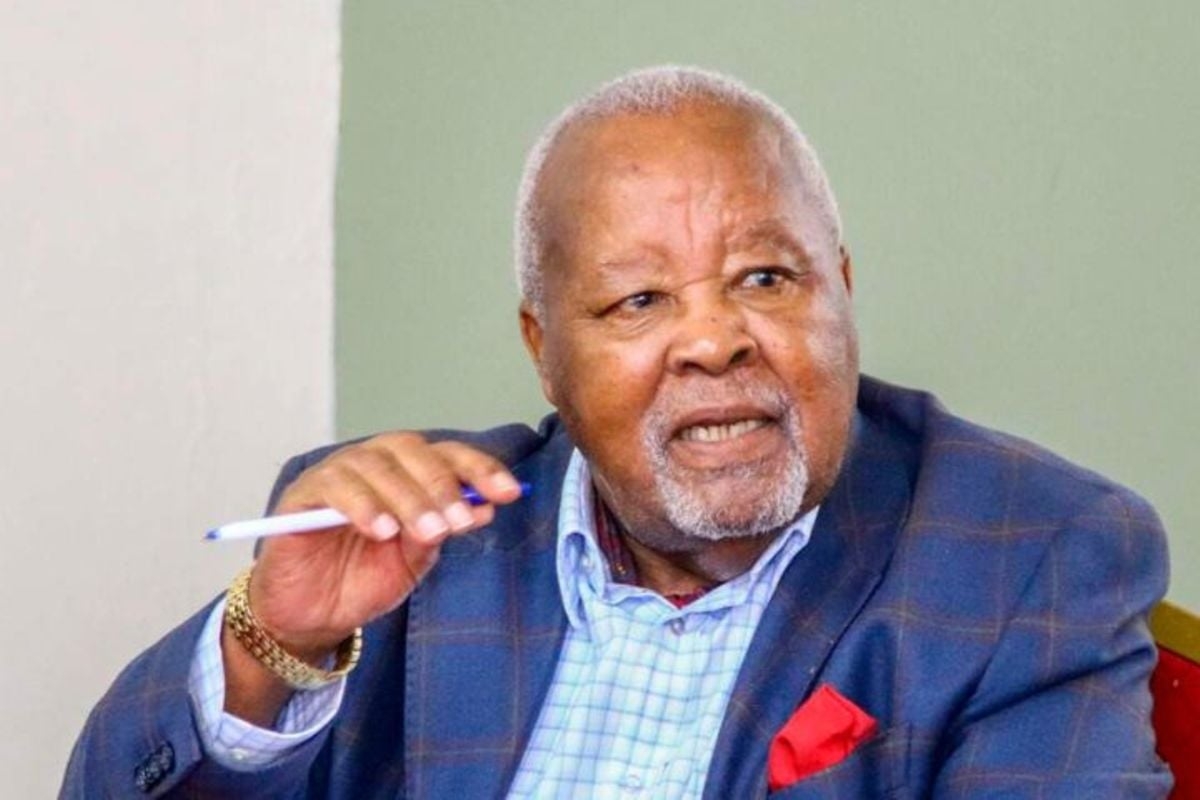

From Harry Thuku to Tom Mboya, it was easy to combine the issues of political rights with trade union matters. After independence, it was difficult to establish a clear dichotomy between government and trade unions.

Many labour leaders, if not all, had joined the government and, in key positions. Trade union leaders had to choose to align with either Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s KNFTU or Tom Mboya’s Cotu.

Eventually Cotu prevailed, but its dalliance with the government through the pioneer Secretary General, Tom Mboya curtailed its independence.

It remained at best an agitator for minimum wages at Labour Day celebrations. The workers’ conditions of service remained squalid and sordid in most industrial outfits.

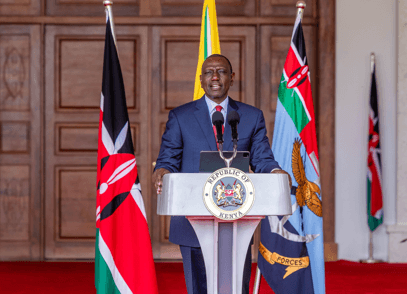

Then came the Uasu after the 2002 elections that swept President Mwai Kibaki into power. Their leadership was sophisticated in their engagement with the government. Having suffered decades of repression from government agencies, they comfortably leaned left.

They took to the old strategies of the classical communist manifesto. They adopted the ideologies of socialist political organisations and became the face of trade union movement in Kenya. Knut and later, Kuppet, had to kowtow to the Uasu sloganeering.

A lot of success has been recorded since then and the conditions of service for the academic staff has improved tremendously.

Significant work still needs to be done to bring the terms of service to optimal levels, though. That is the reason for the recent spate of lecturers’ strikes.

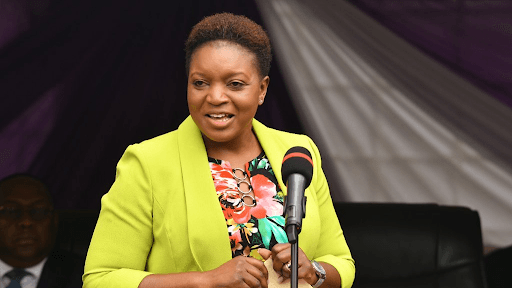

Uasu, like all the unions, have not reorganised themselves and adopted new strategies in line with emerging trends in the labour market.

With technology, there has emerged digitisation of services and labour products. The current and emerging youth are averse to jobs that demand their full time in one station.

They are involved in many high-end digital assignments. Most of these engagements are cutting edge and international in nature.

Unless Uasu

and ilk change tact, these young

people are not their immediate and

future union members.

![[PHOTOS] Ole Ntutu’s son weds in stylish red-themed wedding](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Ff0a5154e-67fd-4594-9d5d-6196bf96ed79.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)