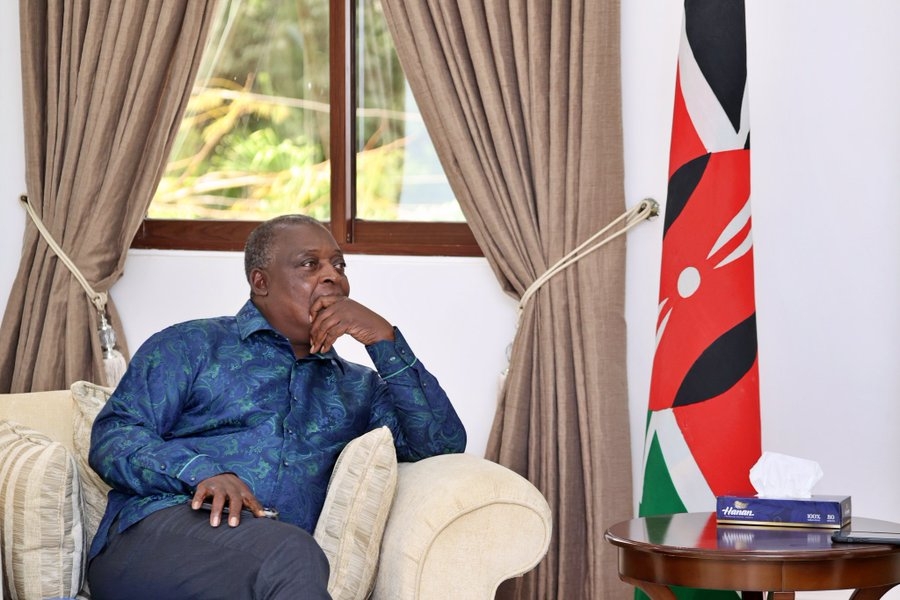

Had he not been a heavy sleeper, Cosmas Ndeti would, probably, have never been the first African to win the Boston Marathon for three consecutive years; 1993, 94 and 95.

Neither would he have had the opportunity to be an earshot away from the then world’s most powerful man, United States of America’s 42nd President, Bill Clinton.

Like many children growing up in rural Machakos, Ndeti, a third born to the third wife in a polygamous family, used to trek for a long distance to school.

“Corporal punishment was still very much alive those days. I used to love my sleep but neither of my siblings could wake me up until they had their breakfast and were off to school,” reminisced Ndeti.

“The Bible says, spare the rod and spoil the child. So, out of fear of being caned by the teachers for arriving at school late, I would quickly prepare myself and run the hilly path to school. Surprisingly, I was always ahead of my brother and sisters. This I believe set me on the path to becoming an athlete.”

The distance between his village and Kyasila Primary School, where he studied between 1977 and 1984 was, according to Ndeti, about 1.5km and he covered the hilly trip in less than 15 minutes, a sure sign that even as a kid, he had the lungs to endure distance running.

Born in Machakos in 1971, Ndeti narrates how he, at about 10, ran against older boys in the zonal races of the former Machakos District and finished sixth much to the awe of onlookers.

“Everybody marvelled at my performance. I was only rounded by the boy who won the 5,000m race. I went on to reach the divisional level in 1983 (and finished fourth).”

At the age of 16, Ndeti’s star began to glamour through running against bigger boys and was part of the Kwa Ngei Secondary School team which defied odds to grace the national cross country championships in 1987. This early feat won the heart of Boniface Nzioka, his father’s cousin and a revered Team Kenya coach for the 1988 Olympic Games, who took up the responsibility to coach him.

Landing in the hands of Nzioka paid dividends as Ndeti clinched a silver medal in his first international race, the 1988 Auckland Cross Country Championships in New Zealand, aged 17.

The road to competing in a life-changing Boston Marathon started after his life-long friend, Benson Masya, invited him to run in Honolulu in 1992, where he finished second behind his host.

But before that, Ndeti had gained employment with a Japanese firm after they promised him a contract if he won the 1990 World Junior Championships in Bulgaria. He not only won the race but also broke the course record, clocking 59:42 in a 20km road run.

Upon employment in Japan, thanks to legendary coach Shunichi Kobayashi — who linked him up with Konica, Ndeti resigned from his previous employment at Postal Corporation of Kenya. He would soon hand in another termination notice in Japan after winning $5,000 (about Sh500,000 by today’s conversion) at the Honolulu Marathon, a figure that was his annual income in Japan.

“I won what I was earning in a year, in two hours? I went back to Japan and resigned after realising they were misusing me,” he said.

Boston Marathons

Soon after gracing the World Half Marathon in Honolulu, Ndeti and Masya were invited to run at the 1993 Boston Marathon.

They used the same tactic they used to win the Honolulu Marathon where he would keep up with his friend. Only that during the race, his companion was sick, which led them to fall off the lead pack.

Upon realising Masya’s situation, Ndeti charged away from his mate, from twenty-second to catch up with the likes of Ibrahim Hussein and Sammy Lelei, who were in the top three positions.

“I was feeling very strong, the commentators did not know my name so they would identify me with my bib number,” he said.

“There is a hill called ‘the heartbreak hill’ on the course and I charged uphill from the twenty-second position to join another Kenyan, Boniface Marande, at fourth. I asked him how many people were in front of him because I could not see any and he told me only three were ahead,” he said.

The 49-year-old nostalgically remembers how he went on to awe everyone by winning the race as the Kenyan least expected to win.

“I did not know what to do after I won. I remember I just sat down and I realised there was a policeman who was accompanying me. He took me to the podium where the Kenyan flag was raised and the national anthem was played,” he said.

Masya finished 22nd and was surprised to learn that his friend Ndeti had won the race.

As was the custom in those days, Ndeti was briefed of an imminent trip to the White House where he was privileged to run with the then President of the US, Clinton.

On the two-hour flight to Washington, he was the only black man on the plane and it was announced to the passengers that the Boston Marathon winner was on board.

“Everyone came to me and they were asking for autographs,” he said.

In 1994, despite winning the previous edition, Ndeti felt like he was an underdog in the race owing to the fact that he came up against a star-studded line-up.

“I was running against Moses Tanui, who had three pace-setters, Andres Espinosa, the New York Marathon winner and Hwang Young-Cho, the 1992 Olympic marathon winner. It was the toughest race I ever ran and no one predicted I could win,” he said.

“But I was in the greatest form since I was well prepared. I had trained in Japan, Southport, England and Embu. The weather was also perfect since there was a tailwind.”

He beat the course record in dramatic fashion as he sprinted away from Espinoza. He clocked 2:07:15.

Ndeti ran in Portugal in preparation for his third Boston Marathon but placed 22nd in the Lisbon road race, a factor which made everyone undermine him at the 1995 Boston Marathon.

“I was not even interviewed and the race director did not come to pick me up as it was the tradition — to pick the defending champion from the airport. They all expected me to perform badly,” he said.

He won the race to become the first African to win the marathon three times in a row.

Though 20 years later Auma Obama would become the first Kenyan to ride in the official limousine of an American President when he hitched a hike in his brother, then US President Barrack Obama in 2015, Ndeti had, in the aftermath of his 1995 Boston Marathon triumph, been given the rare honour of sharing a solo ride in the unofficial limousine with Clinton, on their way to the customary post-race jog.

“I remember, we sat down like old friends. He put his arm around me, and we had a conversation,” he said, indulging in reminiscence.

Ndeti had given his life to Christ two months before his first race in Boston and with a replenished zeal in his heart, likened the race on the course to a spiritual competition.

He went on to make a fourth appearance in the prestigious marathon in 1996 to become the only Kenyan to achieve such a milestone. He finished third.

Following appearances in the 1996 New York Marathon, 1997 Fukuoka Marathon and Nagano Olympic Commemorative Marathon in 2000, he hung his ‘Pegasus’ sneakers in 2003 after nagging injuries and poor training.

A man with a photographic memory, Ndeti named his firstborn son Boston, who was born a month before his maiden appearance in the race that introduced him to the world. To him, it was the toughest course he ran but because of his boyhood experience of running uphill, he relished the experience and holds fond memories of.

“Boston is my capital city because that is where my fame came from. Some people call me ‘the Boston man’,” he intimated.

“My clothes and the shoes I wore when I broke the course record were expensively sold. They are at the Nike Headquarters in Oregon.”

He divulges he was selected to be part of the 1996 Olympics but opted not to attend.

“I decided to go to the New York Marathon because of the appearance fee. Had I gone to the Olympics, there is nothing I would have gotten,” he said.

Church and Athletics

In August 2010, a born-again Ndeti set out to start a church, the Christ Deliverance and Destiny Chapel, in Kitengela. After winning hearts on the racecourse, he felt it was time to win souls for Christ and thus he built the church ‘to do the Lord’s work’.

“I have seen God’s blessings in my life and I wanted to give something back,” he said. “This is not an investment, it is a calling. I decided to do it to give back to God.”

Ndeti went on to reveal how, through his church, the lives of many have been changed.

“I have witnessed God in this ministry. Some people have come here for healing and have confessed their blessings in front of our congregation,” added Ndeti, who ministers with his wife, Reverend Jane Ndeti.

And even while nourishing souls with the word of God, Ndeti narrates how he has coached and mentored powerhouses from the Ukambani region, who have dominated the track.

“Most of the athletes from Ukambani region are my products. Patrick Makau, who was once a world record holder, is my product as well as Jimmy Muindi, who won the Honolulu Marathon seven times,” he observed.

While revealing that he invested about Sh8m in his church, Ndeti opined that setting up an athletic academy would be an expensive venture. He even revealed that his ambitions to progress into athletics governance has been hampered by leaders who bar former athletes from vying for leadership positions.

“I have tried but the people at Athletics Kenya cannot let anyone who understands an athlete’s pain to hold a seat,” he alleged.

“But we are trying to form a club which will take over matters athletics in Ukambani region.”

When asked about the region’s capacity to challenge athletes from the Rift Valley, he said: “It is possible. We used to be afraid of them in the ‘80s. But with the right coaching and diet, we can out-do them.”

Doping

A father of three, Ndeti’s career encountered blemish after he was banned for three months following a failed test for ephedrine at the 1988 World Cross Country Championships.

Though he does not concede this fact, he inculpates the issue of doping to the managers and hangers-on handling athletes in the country. According to him, the integrity of the sport has gone to the dogs.

“The officials are involved. They know what is going on. They just want to make money and make the sport interesting for the fans,” he said.

Concluding his lengthy sit-down with The Star, Ndeti revealed he still holds an ambition to return at the Boston Marathon as a guest and reckons if it ever comes to pass, he will be a ‘busy man’.

“I hope to visit the place again and I know they may even facilitate my stay because I am a legend on that course. I know, if people will be aware of my presence, I will be a busy man because of the autographs I will have to sign,” he avowed.