Are you thinking about learning a language? Perhaps you’ve decided that it’s time to dust off your classroom French. Maybe you’re planning a trip to Japan and feel like you should make the effort to learn the basics, or work is sending you to the Cairo office for a year and you’ll need Arabic.

Learning a language is a hugely worthwhile endeavour, but two things are certain: it will take a while, and motivation will be crucial.

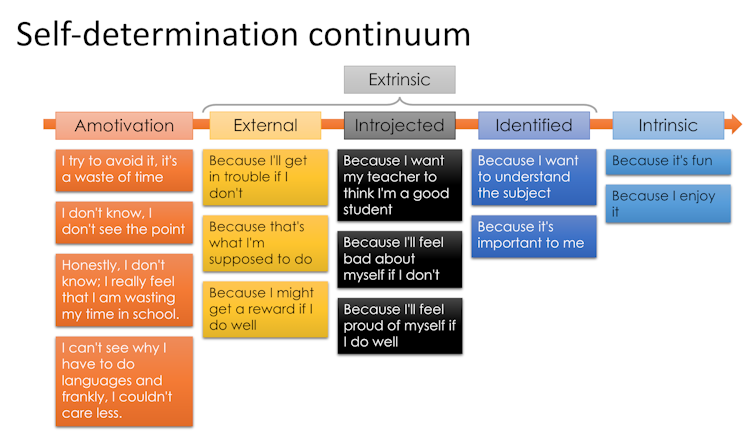

I research language learners’ motivation, using what is known as self-determination theory to measure motivation. This theory proposes that there is a continuum of motivation.

The continuum starts from the least motivated – “amotivation” – where you might resist doing a task, perhaps because you can’t see its value. The highest form of motivation is “intrinsic motivation”, which means you do something because you find it fun.

In between, along the continuum, there are different forms of motivation. Our motivation increases as we perceive the activity to be more and more aligned with our own beliefs and values.

Self-determination theory is increasingly popular among researchers looking to explore language learning. It tells us that if you are learning a language because you think it’s important to you – because it fits with your beliefs and values – then you will want to do it. It’s not enough to know that language learning might be a good thing in the abstract; you need to find personal relevance in it.

You can try to build this motivation by setting yourself goals that revolve around connecting meaningfully with others – such as improving your ability to communicate with friends, family or colleagues in their language.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Is the ‘barefoot-boy summer’ trend bad for your feet? Experts explain

How to make your next holiday better for the environment

Treat culture: why indulging in small, affordable pleasures can help you cope with tough times

You are more likely to persevere and to do better if this is your motivation to learn, than if you are doing something for a more controlled, external reason, for example, because your boss expects it. It’s likely to make you feel happier, too.

This is why compulsory language learning in schools doesn’t necessarily yield the results we might hope for. Students often don’t have a sense of autonomy about undertaking the study in the first place.

Keep going

As well as feeling that you’re studying for your own goals, other important factors can keep you motivated on your language journey.

One key factor is known as relatedness. This means having positive relationships with those around you – your teacher, your classmates, your friends and family – and helps you thrive and find meaning in what you’re doing. If your partner supports your language learning and encourages you, you’ll be more likely to find that you’re keen to continue.

Another is competence. This is not about being the best at everything, but about feeling capable. So even if you’re a beginner, you can feel a sense of competence if you take your learning step by step and feel confident in your ability before moving on.

If language learning app Duolingo, for instance, has been telling you you’re “amazing” and the lesson is “no match for you”, you may well feel enthused to continue.

Duolingo has been incredibly popular as a way to learn a language, either instead of or alongside traditional methods such as books and lessons. Part of the model of this and other language learning apps is to reward users at every turn – for using the app on consecutive days, for completing a certain number of exercises, and even for engaging at certain times of the day.

But self-determination theory research tells us that rewards can also be demotivating.

When life gets in the way or you find a lesson particularly hard and the rewards stop, you may feel adrift. The best way to find the will to keep going is to find that personal reason to learn – and remind yourself of it when the going is tough.![]()

Abigail Parrish, Lecturer in Education, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.