Shocking details have emerged of a deep cash crisis threatening the effective delivery of justice to Kenyans.

A new report reveals several projects, programmes and services meant to ensure optimal delivery of justice have stalled as the Judiciary faces a budget shortfall of between Sh20.75 billion and Sh43 billion amid a rising case backlog.

This is even as the Judiciary, charged with the administration of justice, wobbles in deep debt as it struggles to deliver on its mandate.

The report on the State of the Judiciary and the Administration of Justice for 2023-24 reveals the institution has accumulated pending bills amounting to Sh811.17 million, up from Sh608.07 million in the 2022-23 financial year.

This includes Sh410.01 million in development bills and Sh331.92 million in recurrent bills. Court and arbitration awards account for Sh69.24 million.

“The rise in pending bills was mainly attributed to exchequer releases challenges,” the report says.

The dossier tabled in the Senate by Majority Leader Aaron Cheruiyot reveals the sorry state of the institution, which is unable to fund its key operations and programmes.

“Currently, the allocated budget per case is Sh40,700. However, from an internal review, it was established that optimal cost per case is Sh125,750,” the report says.

“During the FY 2023-24, 516, 121 cases were filed and therefore to dispense with them within a year, it would require optimal funding of Sh64 billion.”

This, the report says, was against the allocation of Sh21 billion, translating to underfunding of Sh43 billion or Sh85,050 per case.

Even with the Sh40,700 allocated per case, the report shows the Judiciary still had underfunding of Sh20.75 billion as it was only allocated Sh22.42 billion.

Consequently, crucial projects, programmes and services worth Sh20.75 billion meant to take services to the people and ensure faster dispensation of cases have stalled.

“Inadequate funding of the Judiciary adversely affected the implementation of a number of critical activities,” the report states.

Case backlog has also ballooned over the years due to a lack of funds to hire more judicial officers to clear them.

“Pending cases rose by 1.2 per cent from 625,643 to 649,310 particularly affecting the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, magistrates’ courts and small claims courts,” the report states.

“Rising case backlog occasioned by, among other things, low judicial officer to caseload ratio and steady growth in the number of filed cases from 402, 243 to 2017-18 to 516,121 in 2023-24.”

The Judiciary Service Week, circuits, special benches and pro bono services whose budget was Sh301 million have all suffered due to underfunding.

Capital projects valued at Sh6.31 billion and the digital strategy and automation programme valued at Sh2.35 billion have stalled.

The Sh418 plan to roll out court-annexed mediation and alternative dispute resolution has also taken a hit.

Further, the Judiciary’s plan to operationalise new courts and small claims courts for Sh907 million has stuck.

The development budget was slashed by Sh500 million, from Sh1.9 billion in the previous year to Sh1.4 billion during the year under review.

“The absorption rate also declined by 12 percentage points, from 78 per cent in 2022-23 to 66 per cent in 2023-24 mainly due to unfunded exchequer requests,” the report says.

The Judiciary has remained underfunded for several years despite the establishment of a Judiciary Fund.

The law provides that at least three per cent of the national budget should be allocated to the courts.

“For the past three financial years, the Judiciary has consistently received less than Sh0.92 per cent of the national government budget, below the recommended three per cent,” the report says.

“This perennial underfunding, especially when compared to the allocations for other co-equal arms of government, has substantially undermined the Judiciary’s efficiency, financial independence and operational autonomy.”

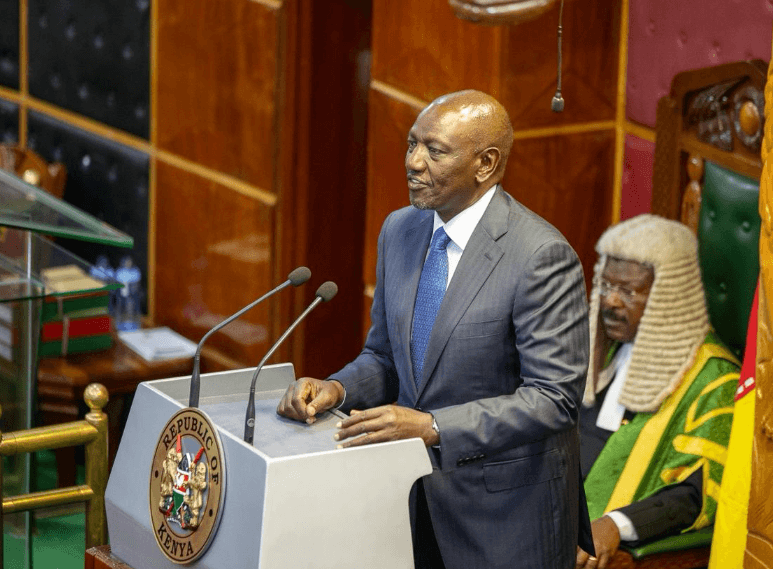

The revelation is an indictment of President William Ruto, who has maintained since his election that he would increase the Judiciary’s budget by Sh3 billion annually for effective dispensation of justice.

“Our campaign for the financial independence of the Judiciary has paid off with the implementation of the Judiciary Fund. My administration will scale up the budgetary allocation to the judiciary,” he said during his swearing-in in 2022.

Chief Justice Martha Koome has often lamented about underfunding, saying the shortfall was affecting operations of the institution.

In July, she suspended the hiring of Court of Appeal judges due to a budget cut.

“This directive has far-reaching consequences on the operations of the Judiciary and the JSC,” the CJ stated.

During the year under review, the Judiciary received Sh22.42 billion, an increase from Sh18.56 billion in 2021-22 and Sh21.13 billion in 2022-23.

“The Judiciary’s budgetary needs have consistently fallen short, with funding gaps of 48 per cent, 47 per cent and 48 per cent over the past three years,” the report states.

Further, the report shows that during the year, the courts collected a total of Sh2.94 billion comprising fees and fines, comprising Sh1.46 billion and 1.19 billion respectively.

In addition, revenues collected from interest on deposit, rent of property and other income amounted to Sh270 million and Sh23 million respectively.

“Fines constituted the major portion of the revenue component to the Judiciary at 49.75 per cent whereas rent from property and miscellaneous income made up 0.79 per cent of the total revenue,” the report says.

Court deposits held at the close of 2023-24 amounted to Sh8.43 billion, an increase of Sh380 million from the previous year.

The report shows that the Judicary achieved tremendous milestones in an attempt to clear cases.

Out of the 516, 121 cases filed during the year, 509, 664 were resolved, translating to a case clearance rate of 99 per cent.

Criminal cases made up 57 per cent of the total filings, showing a three per cent decrease from the previous year.

In contrast, civil cases increased by three per cent, continuing a four-year growth trend.

“The courts improved efficiency, with a 14 per cent increase in resolved criminal cases and a 32 per cent rise in civil cases, leading to a reduction in backlog,” the report says.

Pending cases rose by 1.2 per cent from 625,643 to 649,310, particularly affecting the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, magistrates’ courts and small claims courts.

“The high and rising caseload per adjudicator at the small claims court [leads] to burnout and non-compliance with statutory timelines,” the report says.

![[PHOTOS] Betty Bayo laid to rest in Kiambu](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2F3b166e2e-d964-4503-8096-6b954dee1bd0.jpg&w=3840&q=100)