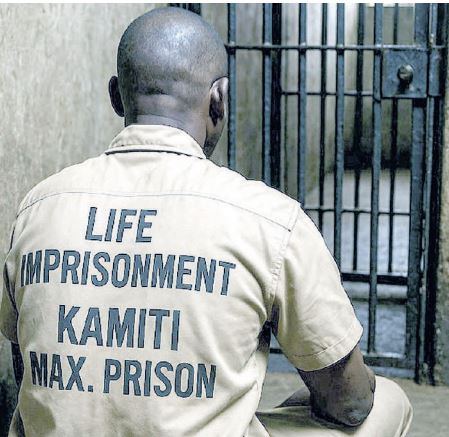

Life imprisonment is a sort of living death.

Various Kenyan courts have said life

means life – and have held that (unlike other prisoners) a lifer cannot benefit

from remission —having their sentences reduced for good behaviour.

It

means that the idea of rehabilitation and re-entering society is not prominent

in the treatment of lifers, though in fact most do work. A sensible provision

for annual reports on lifers, their behaviour and their condition, in the

Prison Rules 1963, is not working, and has maybe never worked.

So lifers can be released only by the President on the recommendation of the Power of Mercy Advisory Committee (POMAC). The number of lifers applying has been increasing – to 94 in 2023-24.

Unfortunately, POMAC gives numbers of petitions in its annual reports, but not outcomes of petitions. Apparently by about 2022 “199 long term offenders majority of whom were on life imprisonment, had been released through the grant of pardon.”

I have failed to find gazette notices

listing approved petitions for pardon. Those published years ago gave names

only. A prisoner is allowed only two applications to POMAC – and the second

only if there is new evidence. This is much less effective than those 1963

Rules could have been in giving hope of release.

The

story

Various

Acts of Parliament set life imprisonment as the maximum punishment for certain

crimes. Some Acts make life the only sentence in some circumstances, including

the Sexual Offences Act that makes it the only sentence for defiling a girl

under 12.

In

2011 Evans Ayako was sentenced to life imprisonment for defiling a 6-year-old

girl. In May 2017 his appeal was rejected by the High Court. In December 2017

the Supreme Court decided in the Muruatetu case that fixing the death sentence

for anyone convicted of murder was unconstitutional.

In

2023 Ayako’s appeal to the Court of Appeal was heard. By then the Court of

Appeal had begun to apply reasoning similar to Muruatetu to other sentences

fixed by law – or where a minimum sentence was fixed. In fact the DPP lawyer

agreed with the argument that the fixed life sentence was unconstitutional. The

Court of Appeal described at some length the way many countries have chosen to

abolish sentences of unclear length, and decided that “life” in Kenya should

mean 30 years.

This year the case reached the Supreme Court.

That court declared Court of Appeal

decision wrong. I find a lot of difficult, even worrying, issues in these two

decisions.

In

the Court of Appeal

One would imagine that Court of Appeal judges would endeavour to make their judgments “Supreme Court-proof”. In Ayako the Court of Appeal could have gone into more detail, applying Muruatetu reasoning to the case in front of them.

For example, a fixed sentence makes mitigation (the convict trying to convince the

court to be lenient in sentencing) irrelevant, goes against the constitutional

concept of fair trial (though of course the death sentence is so grave that the

consequences are even more serious).

The

Court of Appeal did mention that the failure to allow mitigation violates the

right to equality, and also is contrary to respect for the person’s dignity

(points made in Muruatetu). They added that life imprisonment is cruel and

inhuman punishment (against Article 29(f)). Overall my sense is the judgment could

have been more detailed. But did they think that it would never get to the

Supreme Court because the DPP had been in favour of their judgment?

It is often said courts are not the best place for complex social realities and the legal responses to be analysed and decided. This is one such situation – there is a huge variety of ways countries have dealt with the life sentence issue.

It is impossible to say there is international consensus on the solution even if there is on the problem.

But a court must find a solution as well as identify a problem. The court chose to make that solution fixing “life” at 30 years. But what happens if a prisoner is really not able to be released into society? What about other sentences?

Could a court, in a case involving a maximum of life,

actually impose a fixed sentence of 40 years? Many loose ends remain.

The

Supreme Court in Muruatetu urged action on life imprisonment by government.

Nothing has happened. Did the Court of Appeal, I wonder, hope that their

judgment would push government or Parliament (or even the Law Reform

Commission) into doing something about life sentences?

In

the Supreme Court

Why

did the DPP appeal against a decision that the office had supported? A new DPP

came into office not long before the Court of Appeal decision in Ayako. I hope

the decision to appeal did not arise because of the change of an individual –

or worse from government pressure. Or maybe the office hoped for a Supreme Court ruling on

this complex issue.

The

Supreme Court held that the Court of Appeal had no power to decide that the

sentence was unconstitutional because that argument had not been raised at the

High Court.

This

is the usual rule. The consequences are serious. Muruatetu presented the

possibility of a new approach to mandatory sentences. It was decided between

Ayako’s High Court and Court of Appeal hearings. The traditional approach means

that someone like Ayako could never raise a new line of argument even if it

would have been almost unimaginable earlier. And how about people with no, or

incompetent, lawyers?

I am

also very doubtful about the court’s view that, because Article 165 gives the

High Court the power to make constitutional decisions, no higher court can do

it except on appeal. This is the constitution; every court is bound by it.

The

Supreme Court held that such matters should be decided not by a court but by

Parliament, with public participation. Yet the court had done just that by

declaring the mandatory death sentence unconstitutional without public participation

– though with the support of the Attorney General and DPP. And, as implied

earlier, we may have to wait forever for Parliament.

The

Supreme Court began retreating from its Muruatetu position soon after the

decision. True, the consequences of Muruatetu were complicated, involving

resentencing a large number of people. And then some courts began to apply it

to other fixed or minimum sentences. In 2021 the court issued “directions”

which said their Muruatetu judgment did not invalidate “mandatory sentences or

minimum sentences in the Penal Code, the Sexual Offences Act or any other

statute”. That was correct. But courts

analysing earlier decisions, including of higher courts, and deciding whether

the reasoning can apply to a different situation is how law develops. It is the

fundamental technique of the common law. And although the actual decisions on

law of the Supreme Court are binding on lower courts, their observations on

what they did not decide are not – even if they should be treated with respect.

The

problem here is that the court largely treated “life” as a matter that should

not have been decided. It did not set out fully why the court thinks a

mandatory penalty for murder differs from others. It seems to be thinking that

its “directions” end the matter – no other fixed or mandatory sentences are

unconstitutional.

A

final matter for concern is the presence, not just as a member of the Supreme

Court but sitting on the bench in this case, of Justice Njoki Ndung’u. As MP,

she sponsored the Sexual Offences Bill as a private member’s bill. It would not

be considered appropriate for a judge who decided a case in a lower court to

sit on appeal on the same case, and I suggest it is not appropriate for the

architect of a Bill to sit as a judge to help decide its constitutionality.