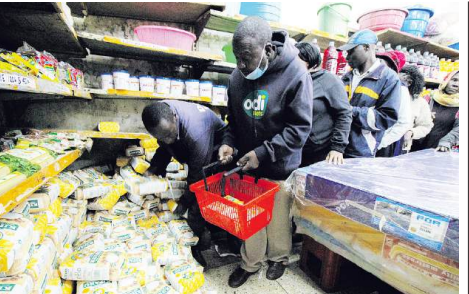

It is not the soaring speeches in Parliament or the glamorous handshake deals that define the state of a nation. It is the price of unga. It is the cost of a pad that keeps the teenage girl from attending school.

It is the amount of money a parent needs to buy school uniform, a pencil. It is the electricity bill that keeps rising even when there’s no power, the water bill when the taps are dry. It is in these everyday mundane struggles that the soul of Kenya is being drained. Today, the cost of living in Kenya is not just a policy debate; it’s a matter of survival.

For millions, life has become a daily negotiation with hunger, homelessness, unemployment, debt and despair. And while citizens tighten their belts, our political elite appear to loosen theirs — gorging on the trappings of power, slurping tasty rich soup, globetrotting, and scheming their next coalition while ordinary Kenyans ask themselves how they will survive the week. We are in a moment of reckoning.

The much-touted promises of a people-centered government are being tested against the brutal realities of economic hardship. And so far, the leadership is failing this test. The people are on their own.

Kenya has always had politics full of drama, but rarely has it felt so detached from the daily struggles of the people.

The high cost of living is not merely a function of global economic turbulence as government fat cows are wont to claim, it is largely the product of domestic policy choices, fiscal indiscipline, grand theft and a political culture that prioritises survival in office over service to the citizen.

Every time a budget is read, it seems tailored to please creditors, not citizens. Every tax increase feels like a punishment for being poor.

When fuel prices go up, matatu fares rise, food prices follow, and the ripple effect chokes families from all corners of the republic.

Yet, in the same breath, we see billions allocated to offices and functions whose public utility is questionable at best. The economy is being funded in a way that puts the next deal above people.

Our debts are mortgaging the future of our children, and even now, there’s little clarity on where the money we borrow goes.

The talk of development must be tempered with the question: for whom? The middle class, once considered Kenya’s great stabiliser, is shrinking. Salaries remain stagnant as inflation roars. University graduates are flooding the job market, only to be absorbed into gig jobs with no social security.

Professionals are taking loans to afford basics, and many now live from M-Pesa to M-Pesa and from one mobile loan app to another.

At the bottom of the pyramid, things are far worse. Families in the informal settlements of Nairobi, the arid plains of Turkana, or the sugar belt of Western Kenya are surviving on one meal a day.

Healthcare is increasingly inaccessible, while school levies and hidden charges have undermined the idea of free public education. It is not that these citizens do not understand politics. It’s that politics, as it is practiced, is alien to the will of the people.

The political elite often speak a language of power-sharing, electoral reform, reconstituting IEBC and constitutional amendments, while the people speak the language of survival: “How will I feed my children? Where will I get money for the two months’ rent arrears? Where will I get school fees? Why is water a luxury in a country full of rivers?”

One must ask: Has the ‘bottom-up’ economic model trickled down any tangible benefits, or has it been hijacked by the same cartels and cronies who have long benefited from state capture? Are the young people who were promised jobs, tenders, and credit now better off, or simply more disillusioned? It is time for truth-telling.

Political branding and sloganeering are not substitutes for good governance. Neither is blaming the past a sufficient excuse for failing to deliver in the present. We are witnessing a broader crisis of political representation.

Elected leaders rarely speak for the people anymore—they speak for themselves, their financiers, and their future ambitions.

Politics has become a career, not a calling. We are governed by a political class that doesn’t feel the pain of its people. But there is hope yet. There is a slow but growing awakening among Kenyans. Civic education is being revived. Youth are mobilising online.

Public participation, once a sleepy formality, is now becoming a battleground of ideas and accountability. Kenya is not short of potential. We are a resilient people. But resilience must not become an excuse for silence.

If leadership will not rise to meet the people’s needs, the people must rise to redefine leadership. Leadership must return to its roots— service, sacrifice and solutions.

The writer teaches

Globalisation

and International

Development

at Pwani

University and is

a Programmes

Associate at DTM, a

Media CSO

![[PHOTOS] Ruto at Pope Francis' burial](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F04%2F844cb891-abd4-4ee5-bc2d-2a0c21fa3983.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)